Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (28 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

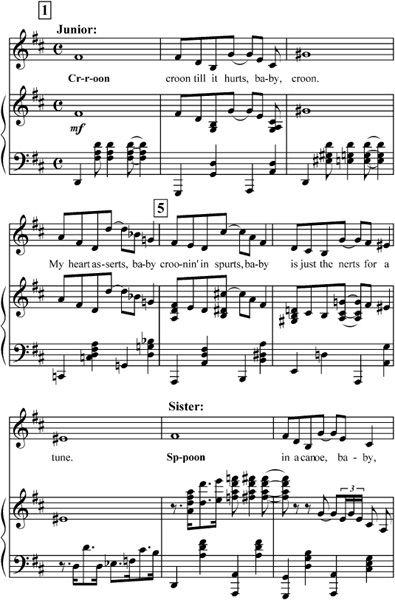

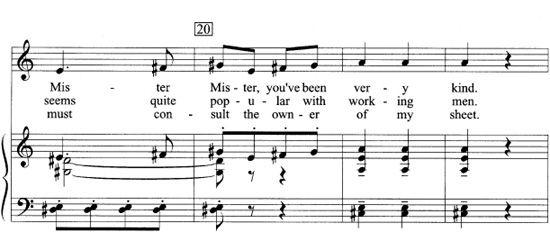

Example 6.1.

“Croon-Spoon” (beginning)

The punch line of the final A derives from the inability of either Junior or Sister Mister to successfully resolve the harmony. After six measures, Junior should be ready to conclude the song one measure later to preserve the odd but symmetrical seven-bar units of the first two A sections. Instead, Sister Mister, after a fermata (a hold of indefinite length), repeats her brother’s last three measures and Junior, after another fermata, repeats the third measure one more time before the siblings screech out the original tonic to conclude the thirty-nine-measure tune.

Following Brecht and his own evolution as a reformed modernist with a social agenda, Blitzstein is of course telling us to avoid singing what he considers to be vapid songs about croon, spoon, and June, even as Junior tells us in the bridge of this song that “Oh, the crooner’s life is a blessed one, / He makes the population happy.” Junior concludes his song with his own didactic message directed toward the poor who are “not immune” to the wonders of croon spoon. “If they’re [the poor] without a

suit

, / They shouldn’t give a

hoot

, / When they can

substitute

—CROON!” In

Pins and Needles

, the inspired and phenomenally popular revue presented by the International Garment Workers Union the same year as

Cradle

, Rome asks

his audience to “Sing a Song of Social Significance.” “Croon–Spoon,” a song far removed from social significance, serves as a forum in which Blitzstein can lambaste songs that do not respond to his call for social action and provides the composer-lyricist with an irresistible opportunity to ridicule performers who sing socially useless songs.

31

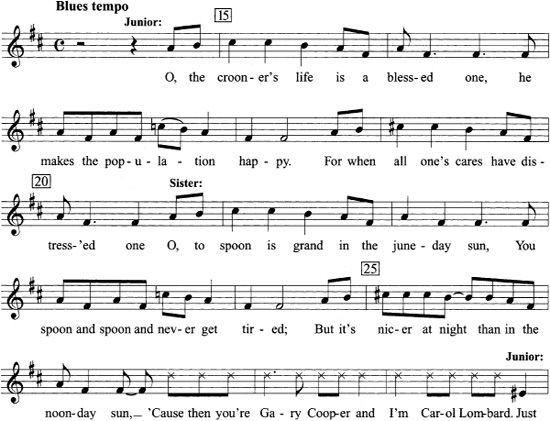

Example 6.2.

“Croon-Spoon” (B section, or release)

Lawn of Mr. Mister: “The Freedom of the Press” and “Honolulu”

During the Windsor run of

Cradle

, Blitzstein concluded an article, “On Writing for the Theatre,” with some remarks on the relationship between theory and practice in this work.

When I started to write the

Cradle

I had a whole and beautiful theory lined up about it. Music was to be used for those sections which were predominantly lyric, satirical, and dramatic. My theories got kicked headlong as soon as I started to write; it became clear to me that the theatre is so elusive an animal that each situation demands its own solution, and so, in a particularly dramatic spot, I found the music simply had to stop. I also found that certain pieces of ordinary plot-exposition could be handled very well by music (

The Freedom of the Press

is a plot-song).

“The Freedom of the Press” begins immediately (

attacca subito

) after Mr. Mister excuses Junior and Sister Mister, an exit underscored by the vamp that began “Croon-Spoon.” Blitzstein called this duet between Mr. Mister and Editor Daily a plot-song because the song narrates (or plots) the entire process by which Daily reinterprets the meaning behind its title: the freedom of the press can be a freedom to distort as well as to impart the truth. The plot is as follows: Daily reveals that he is willing to sell out to the highest bidder (first stanza, A); Daily expresses his willingness to change a story, that is, “if something’s wrong with it [the story] why then we’ll print to fit” (second stanza, B); and Daily learns that Mr. Mister had purchased the paper that morning (third stanza, Mr. Mister’s final A).

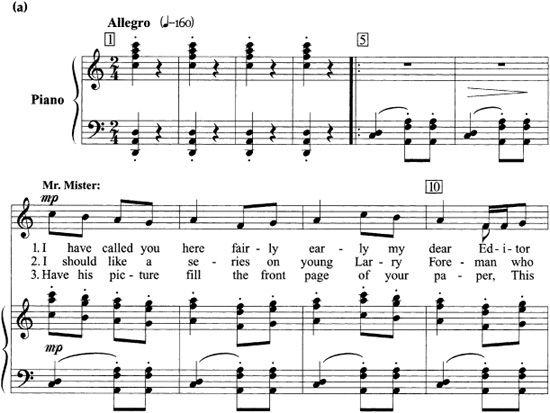

Following a vigorous six-measure introduction, the form of the song is strophic in three identical musical stanzas. Blitzstein subdivides each stanza into an

a-b-a-b-c-d

form, in which the melody of the rapid ( =160)

=160)

a

sections (eight measures each) sung by Mr. Mister are tonally centered in F (concluding in C minor) and the equally fast

b

sections (also eight measures) are answered by Editor Daily in a passage that begins abruptly one step higher in D major (“All my gift …”) and modulates to A major (on “very kind”) before Mr. Mister returns to the

a

section and a D-minor seventh with equal abruptness (

Example 6.3

on next page).

32

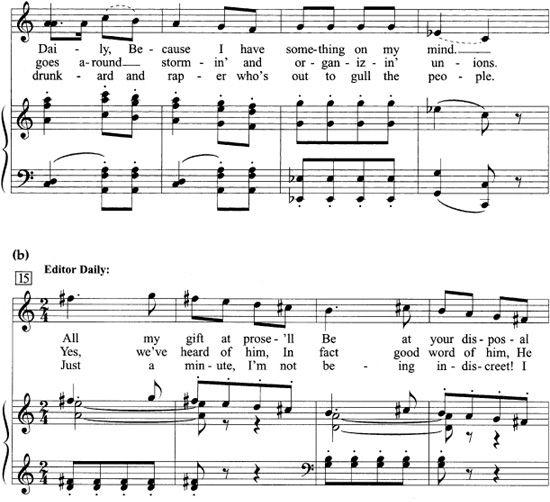

When Editor Daily returns to his

b

section (“Just you call …”), Blitzstein has him sing a whole step higher than his original D major (in E major) for greater intensity. In the brief

c

section Mr. Mister departs from the relentlessness and speed of his (and Editor Daily’s) earlier material and for four measures sings, “

lento e dolce

” (slow and sweetly), the menacing words “Yes, but some news can be made to order” to match the menacing underlying harmony. In the

d

section (twenty measures) the music resumes the original tempo, starting with E major (followed by shifts to C major, G

major, G major, among other less clearly defined harmonies), and Mr. Mister and Editor Daily sing the main refrain. “O, the press, the press, the freedom of the press … for whichever side will pay the best!”

major, among other less clearly defined harmonies), and Mr. Mister and Editor Daily sing the main refrain. “O, the press, the press, the freedom of the press … for whichever side will pay the best!”

33

After “The Freedom of the Press,” the music stops for the first time in the scene, and in spoken dialogue Editor Daily quickly agrees with his new boss that Junior “doesn’t go so well with union trouble” and would be a good candidate for a correspondent’s job “out of town, say on the paper.” Junior and Sister enter to a brief and frenetic dance and jazzy tune, “Let’s Do Something.” Editor Daily, now firmly ensconced as a stooge of his new boss, proposes the “something” that might satisfy Mr. Mister and appear palatable to Junior: “Have you thought of Honolulu?”

Example 6.3.

“The Freedom of the Press”

(a)

a

section

(b)

b

section

In his survey of American music, H. Wiley Hitchcock writes that the first twelve measures of “Honolulu” illustrate “Blitzstein’s subtle transformation of popular song style,” in which “the clichés of the vocal line are cancelled out by the freshness of the accompaniment.”

34

Hitchcock singles out the “irregular texture underlying” the “hint of Hawaiian guitars” in the first eight measures (a four-measure phrase and its literal repetition), the “offbeat accentuation of the bass under the raucous refrain,” which produces a phrase structure of 3+4+1+3+4+1, and an “acrid” harmony (in technical terms, an inverted dominant ninth) on the word “isle.” If the first four measures are labeled A and measures 9–12 B (

Example 6.4

) the overall form of the song looks like this: