Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (29 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

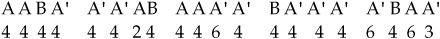

The irregularity of the form and the unpredictability of the less frequent B entrances go a long way to save “Honololu” from the banality it is trying to satirize, just as the unconventional phrase lengths and unorthodox relationship between melody and harmony earlier spared “Croon-Spoon” from a similar fate.

Hotel Lobby: “The Rich” and “Art for Art’s Sake”

If “Croon–Spoon” and “Honolulu” ridicule the vapidity of ephemeral popular music and some of the people who sing these tunes, the songs in the Hotel Lobby Scene (scene 6) convey a more direct didactic social message about the role of artists and their appropriate artistic purposes. Blitzstein saves his sharpest rebuke for the artists themselves, the painter Dauber and the violinist Yasha who meet by accident in a hotel lobby in scene 6.

35

Like the other members of Mr. Mister’s anti-union Liberty Committee, Dauber and Yasha have sold themselves to the highest bidder, in this case to the wealthy Mrs. Mister. The painter and the musician, like the poet Rupert Scansion to follow, have come to the hotel to curry favor with their patroness in exchange for a free meal and perhaps a temporary roof over their heads.

Blitzstein presents Dauber and Yasha as caricatures of artists who, in their espousal of art-for-art’s-sake, have rejected nobler socially conscious artistic visions. The audience learns immediately that they are second-rate artists who fail whenever they are forced to rely on their talent alone. Then, in the course of their initial exchange (a combination of song and underscored dialogue), Dauber and Yasha learn that both of them have appointments with Mrs. Mister. In the ensuing tango (shades of Brecht and Weill), appropriately named “The Rich,” they expose the foibles and inadequacies of the “moneyed people” in such lines as “There’s something so damned low about the

rich

!” and “They’ve no impulse, no fine feeling, no great

itch

!” The answer to the question “What have they got?” is money; the answer to the question “What can they do?” is support you. Clearly Dauber and Yasha hate the rich as much as Blitzstein does.

Example 6.4.

“Honolulu”

(a) A phrase

(b) B phrase

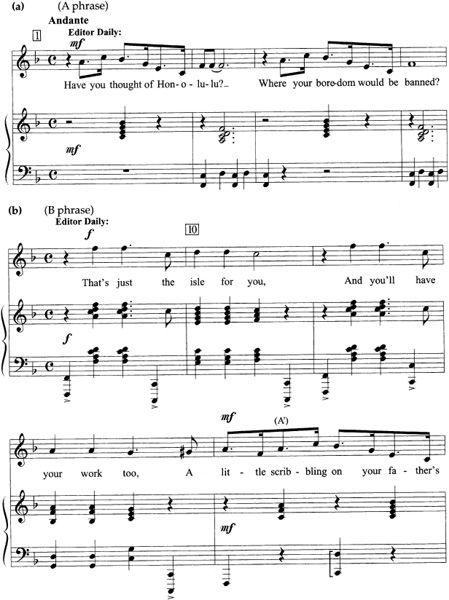

At this point, the object of their scorn, Mrs. Mister, enters to the accompaniment of the horn motive from Beethoven’s

Egmont

Overture based on Goethe’s play of the same name: “you know: ta, ta, ta-ta-ta, ta-ta-ta, yoo hoo!” (

Example 6.5

). In Blitzstein’s satire of

Gebrauchsmusik

, Goethe’s tale of a great man who loses his life in his efforts to overcome the tyrannical bonds of political oppression is demeaned: Beethoven’s heroic horn call now serves as the horn call on Mrs. Mister’s Pierce Arrow automobile. This horn also includes the violin answer that was interpreted by nineteenth-century Beethoven biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer as depicting the moment when Egmont was beheaded.

36

Clearly, the Pierce Arrow usurpation of Beethoven’s horn motif constitutes a sacrilegious use of an art object.

That Mrs. Mister expects Dauber and Yasha to pay a price and kiss the hand that feeds these untalented artists becomes clear near the end of the scene, when she asks them to join her husband’s Liberty Committee, formed to break the unions led by Larry Foreman, a heroic figure analogous to Egmont. This is the same committee of middle-class prostitutes of various professions who were mistakenly rounded up in scene 1 and taken to night court in scene 2 before the flashbacks began in scene 3. Dauber and Yasha are only too eager to oblige, and when Mrs. Mister asks them, “But don’t you want to know what it’s all about?” they reply that they are

artists

who “love art for art’s sake.”

Example 6.5.

Scene Six, Hotel Lobby

Entrance of Mrs. Mister and Beethoven’s

Egmont

Overture

It’s

smart

, for Art’s sake,

To

part

, for Art’s sake,

With your

heart

, for Art’s sake,

And your

mind

, for Art’s sake—

Be

blind

, for Art’s sake,

And deaf, for Art’s sake,

And dumb, for Art’s sake,

Until

, for Art’s sake,

They

kill

, for Art’s sake

All the Art for Art’s sake!

37

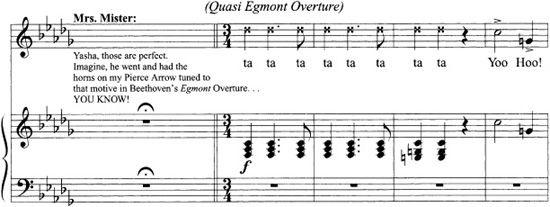

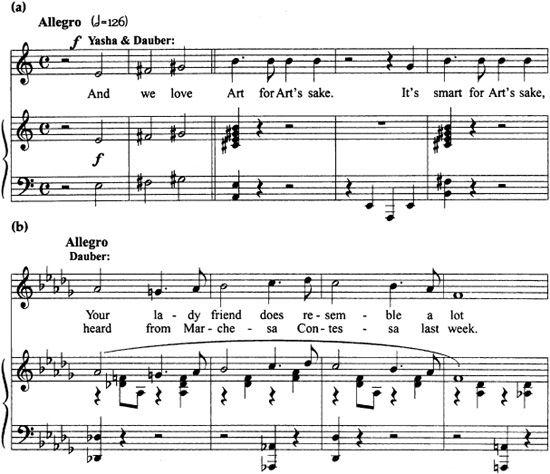

As shown in

Example 6.6a

, Blitzstein’s choice to state each of these lines with a nearly monotonal melody reinforces the pervasiveness of Dauber’s and Yasha’s political vacuity. The fact that Blitzstein reharmonizes the B on the downbeat of each measure with increasingly dissonant chords bears some similarity to the notorious nineteenth-century “Art” song by Peter Cornelius, “Ein Ton,” in which a single pitch is harmonized to an almost absurd degree by evolving chromaticism. Through his relentless dissonant harmonization of the Johnny-one-notes, Blitzstein creates a musical equivalent to support his single-mindedly vitriolic text.

Because Blitzstein himself is a genuine artist, in contrast to Dauber and Yasha, he cannot resist using Beethoven for his own artistic purposes as well. He does this by making two simple rhythmic alterations that effectively disguise the

Egmont

horn motive. The first allusion to

Egmont

occurs in the second chorus of their initial vaudeville routine when Dauber sings “Your lady friend does resemble a lot / Some one, and that’s very queer.” By adding one beat to the first note of the horn motive Blitzstein accommodates the difference between the triple meter of Beethoven’s original motive and the duple meter of the vaudeville routine, a subtle but recognizable rhythmic transformation (

Example 6.6b

). In the second allusion, the art-for-art’s-sake passage previously discussed in

Example 6.6a

, Blitzstein keeps the rhythmic integrity of Beethoven’s motive but distorts it almost (but not entirely) beyond recognition in a duple context with contrary accentual patterns.

Example 6.6.

Scene Six, Hotel Lobby

(a) “Art for Art’s Sake”

(b) “The Rich”

It is possible, albeit unlikely, that Blitzstein’s rhythmic distortions, which parallel his bizarre atonal harmonizations of the B (“

(“

Art

for Art’s sake,” “

smart

for Art’s sake,” etc.) can be interpreted as a critique of Beethoven’s noble purposes in

Egmont

as well as an indictment of Yasha and Dauber’s art. In any event, Blitzstein’s incorporation of Beethoven into his Hotel Lobby Scene goes beyond the conventions and expectations of a musical. It also shows that a revered European master can serve Blitzstein’s artistic as well as satiric purposes.

In contrast to

Show Boat

and

Porgy and Bess

, Blitzstein’s

Cradle

does not offer a grand scheme of musical symbols and musical transformations that reflect large-scale dramatic vision and character development. Unlike their counterparts in the other musicals discussed in this survey, the characters in

Cradle

for the most part sing their songs and then either assume a secondary role, merge into a crowd, or vanish entirely from the stage. The work is episodic within a structured frame; the characters, vividly outlined, are not filled in.

38

It is significant that Moll, the pure prostitute, and Larry Foreman, who represents the juggernaut of the oppressed, are the only characters permitted to recycle musical material. In fact, both of the Moll’s songs are reprised.

The melody of “I’m Checkin’ Home Now,” the first music heard in the show, returns as underscoring for Moll’s spoken introduction to her song “Nickel under the Foot” in scene 7.

39

Before her big scene Moll had sung most of “Nickel” (using other words) in her conversation with Harry Druggist in scene 2. “Nickel” returns a last time in scene 10 against a din of conversation before Larry Foreman and the chorus of union workers concludes the work with a reprise of the title song.

Although

Cradle

has been called “the most enduring social-political piece of the period” and has generally received high marks as the musical equivalent of

Waiting for Lefty

, its didacticism has unfortunately overwhelmed its rich intrinsic musical and dramatic qualities.

40

If other musicals of the time rival

The Cradle Will Rock

as a work of social satire, few musicals of its time (for example, those by Brecht and Weill the previous decade or E. Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen in the next) and few works since combine Blitzstein’s call for social action with a vernacular of such musical sophistication and, yes, artistry.

41

In contrast to many avant-garde works eventually absorbed into the mainstream,

The Cradle Will Rock

, despite its intent to reach a wider public, has managed to sustain its anomalistic status remarkably well. After more than seventy years it continues to resist artistic classification within a genre. It also continues to offend its intended audience of middle-class capitalists through its messages, its devastating caricatures of clergy, doctors, and even university professors, and its occasionally difficult and unconventional score. With due respect to Blitzstein’s sincere didacticism, Blitzstein’s

Cradle

—cult musical, historical footnote, and agent of social change—might, even as it agitates and propagandizes, someday achieve the recognition it deserves as a work of musical theater art (for art’s sake).

42