Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (67 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Despite its fidelity, the film did make a few changes worth noting. “With a Little Bit of Luck” is delayed from act I, scene 2, to scene 4, where it had been reprised onstage. Now the song is both introduced and reprised in the same scene. Also in act I, scenes 6 and 7 are reversed and some dialogue of the former moved to the latter after the “Ascot Gavotte.” The film contains other reordering and some new dialogue here and there that does not effect the placement of songs. The brief exchange between Higgins and his mother that follows Ascot, for example, is new in the film. Between what corresponds to act I, scenes 8 and 9, the film also offers a short scene in which Pickering cancels his bet six weeks before the Embassy Ball.

When Eliza returns to Covent Garden after leaving Higgins, her reprise of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” is sung as both a voice-over and a flashback. Not only are these techniques cinematically useful, but they also effectively demonstrate the extent of Eliza’s transformation. Perhaps now that she is a lady she doesn’t want to wake up her former neighbors so early in the morning. For the most part, however, the film does not take advantage of the possibilities cinema offers to “open up” the show onto a wider “stage” via quick-yet-elaborate scene changes and location settings. One modest exception is the short scene in which we discreetly observe the undressing and bathing of Eliza by Mrs. Pearce and other servants, an offstage event in the theater. The most obvious lost opportunity for cinematic extravagance is the “theatrical” Ascot scene. Although visually interesting with its suitably colorless black and white costuming for the rigid and lifeless upper crust of society—Eliza gets a conspicuous touch of red in her hat to match her inappropriate but refreshing enthusiasm for the event—we hear but do not see the horses actually racing. Perhaps we might conclude that the film adaptation works so well

because

of moments like this one, where cinematic excess is avoided in favor of a consistent, theatrical focus on the principal players and their interactions. At this and many other moments, we are reminded that we are seeing a film of a play rather than an original film—and this is a good thing.

In an effective cinematic juxtaposition, the shot of Higgins’s laughter at the ball when he hears about Karpathy’s erroneous conclusion regarding Eliza’s national identity merges seamlessly with the continuation of this same laughter now shot in Higgins’s study after the ball. When it ran in theaters the film included an intermission after the stunningly beautiful Hepburn descends the staircase in Higgins’s apartment before they leave for the ball (about 100 minutes into the film). On Broadway, the act I curtain closes at the Embassy Ball with the suspense of whether Eliza will be able to fool the wily Karpathy. Theater audiences would have to wait to learn whether

Higgins’s former student would expose Eliza’s lowly origins. Since the film intermission had taken place

before

the ball, Higgins’s laughter provides a welcome linkage between Eliza’s triumph at the ball and “You Did It,” in which Higgins and Pickering insensitively and undeservedly appropriate all the credit for her achievement.

Despite the iconic stature of Cukor’s

My Fair Lady

, Comingsoon.net announced in 2008 that Duncan Kenworthy, who “has produced three of the most successful British films of all time,

Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill

, and

Love Actually

,” all starring Hugh Grant, together with Cameron Mackintosh, the phenomenally successful stage producer who brought

Les Misérables, Miss Saigon

, and

The Phantom of the Opera

from London to New York, have cleared the rights with Columbia Pictures and CBS Films to produce a new version of Lerner and Loewe’s classic. Discussions have begun with their chosen lady, the very fair Keira Knightly, in significant contrast to the casting process in both the stage and earlier film versions, in which the starting point was Higgins. While respectful of Cukor’s treatment, Kenworthy and Mackintosh are confident they can improve on the 1964 original by shooting on location. In their press release Doug Belgrad, a president of Columbia Pictures, espoused the view that “by drawing additional material from

Pygmalion

” Mackintosh would create an updated version that “will preserve the magic of the musical while fleshing out the characters and bringing 1912 London to life in an authentic and exciting way for contemporary audiences.”

21

To reach this lofty prediction Mackintosh will need more than just a little bit of luck.

(1961)

Writers on

West Side Story

seldom neglect to mention that it was the film rather than the stage version that catapulted the show into universal popular consciousness. Indeed, the film, produced by Mirisch Pictures, won ten out of its eleven Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Direction (Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins). The other awards were for Best Supporting Actor and Actress (George Chakiris as Bernardo and Rita Moreno as Anita), Best Art Direction, Cinematography, Costumes, Film Editing, Scoring, and Sound Mixing.

22

With graceful irony, the Academy even presented a Special Award to Robbins, who had been fired from the film after directing the Prologue for falling behind the production schedule. The only nomination that did not result in an award was Ernest Lehman’s for Best Screenplay. Lehman did, however, receive an equivalent award from the Writers Guild of America.

West Side Story

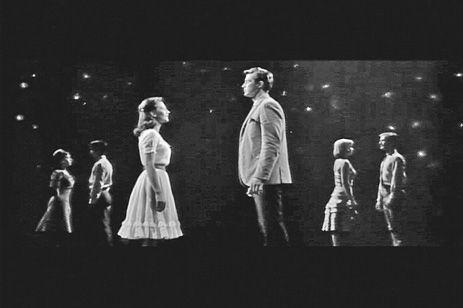

, 1961 film. Tony (Richard Beymer) and Maria (Natalie Wood) meet at the Gym and fall in love at first sight.

In the early 1960s, most movie theaters continued the then-common practice of offering two films for one admission price, a feature presentation and a B-movie. Longer films appeared as a single feature with an intermission, a break in the action that presented an opportunity for audiences to purchase refreshments. At 152 minutes,

West Side Story

merited an intermission. Theoretically, it was possible to divide the film at the end of act I directly after the Rumble and begin the second act with “I Feel Pretty.” Instead, director Robert Wise revamped the scenario and moved the Rumble closer to the end of the story where it was followed rather than preceded by “Cool.”

Despite such adjustments, in marked contrast to the pillaged film version of Bernstein’s

On the Town

and even such relatively faithful film adaptations as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Oklahoma!

, all the

West Side Story

songs are present and accounted for. This may be a first (to be followed by

My Fair Lady

’s film adaptation three years later). Also in marked contrast to

On the Town

and numerous other Hollywood adaptations from the 1930s and 1940s, no songs were added by studio composers on contract or even by Bernstein, although Sondheim was called upon to add and rework his lyrics for “America” in response to the new gender mix. The film also reinstated an overture, which had been deleted from the stage version. It can be heard under the static abstract graphic design with changing colors that

will metamorphose into an overhead realistic cinematic view of the southern tip of Manhattan before the camera makes its leisurely way to the West side, where it zooms in on the Jets protecting their little corner of the island. After diligently observing the musical order from the Prologue to “Maria” (Prologue, “Jet Song,” “Something’s Coming,” “The Dance at the Gym,” and “Maria”), however, the film made changes both large and small to the order of the next nine songs before returning to the stage order for the final songs, “A Boy Like That / I Have a Love,” “Taunting,” and Finale (see the online website for a list of the songs in the stage version).

It might seem strange at first to dwell on the ordering of songs. But consider how important the steps in a story’s telling can be, even a story we know well like

Romeo and Juliet

. Try telling a friend the story in your own words, then compare its impact to Shakespeare’s language. Similarly, the collaborators on the film version of

West Side Story

made a variety of creative decisions about how to re-tell the musical/dramatic story of the show, with the many differences between live theater and film techniques always in mind. Even though the film includes all the songs from the stage version, the sequence in which those songs are presented exerts a strong effect on how we understand the show.

We left off with “Maria.” Onstage, after singing the song based on the name of his new love, Tony continues to call her name until he finds her on her tenement balcony. They then converse and sing “Tonight.” The film follows “Maria” with a scene in Maria’s apartment between Maria, Bernardo, and Anita, during which they move to the rooftop to join the rest of the Shark men and women for “America.” In the film version of this song, the men, absent from the stage version, contrast the women’s positive view of their newly adopted country with sarcastic new lyrics. Only after “America” does Tony reappear in the film and the lovers sing “Tonight.”

More radically, “Cool,” the song that follows “America” in the stage version, is replaced by “Gee, Officer Krupke” and will not be heard until late in the movie, where it directly follows the much-delayed Rumble. Since Riff led the “Cool” song onstage, his absence, as he is dead by this point in the show, necessitated the elevation of Ice (the character Diesel onstage) to lead both the Jets and the song. In the remarks about the show’s genesis we pointed out that in its position in the film, “Gee, Officer Krupke” no longer functions as comic relief after the tragic events of the Rumble, a brief respite between the “Procession and Nightmare” that concludes the Ballet Sequence and the dramatically intense “A Boy Like That / I Have a Love.”

The next change in song order occurs with the earlier appearance of “I Feel Pretty” in the film—in fact, right after “Gee, Officer Krupke!” Onstage, this song, which in the story occurs almost at the same moment as the

Rumble that ended act I (but presented consecutively rather than simultaneously to avoid modernist chaos), opens the second act with a moment of deeply ironic levity. By placing “I Feel Pretty”

before

the Rumble, the irony is lost. In its new position, the song serves as a prelude to the mock, but non-ironic, wedding depicted in the next song in the film, “One Hand, One Heart,” which onstage had occurred after “Cool.” “I Feel Pretty” is notable for the energy of its fast waltz tempo and Maria’s lilting words full of inner rhymes (“it’s alarming how charming I feel”). At every opportunity Sondheim has expressed his dissatisfaction with these lyrics and relates how he tried to remove the inner rhymes but was outvoted. From then until now he has criticized Maria’s lyric as too urbane for a gritty inner-city character.

23

There is some truth to this. But in its new position, “I Feel Pretty” is arguably more in character than it was onstage. The following grim confrontations of the Rumble scene are perhaps more dramatic (or perhaps more cinematic) as a result—even if the complex irony of the stage version is lost.

In another departure of major significance, the offstage voice singing “Somewhere” in the second act Ballet Sequence is replaced in the film by a more realistic and conventional “Somewhere” duet between Tony and Maria. The removal of a dream ballet is typical of other transfers from stage to screen in the early 1960s, where audience expectations called for more apparent realism. Balancing the deletion of this major dance section, several other dances, including the Prologue, The Dance at the Gym, and the now mixed gendered “America” (in the film men as well as women sing and dance this number) are extended.

Realism as a vital component of the Hollywood film aesthetic and the likely motive for removing the surrealistic Ballet Sequence, is considerably challenged, however, by the presence of gang toughs snapping their fingers (painfully with their thumbs and first fingers at Robbins’s insistence) and their balletic and acrobatic dancing up and down a real Manhattan. To better prepare film audiences for this incongruity, Robbins greatly expanded the Prologue, which itself followed an overture in contrast to the stage version. After the abstract drawing of Manhattan seen throughout the overture metamorphoses into realistic aerial footage that ends up on a West side playground and surrounding tenements, the lengthened Prologue allows the Jets to ease more naturally into dance through a series of incremental movements from natural to stylized movements, much in the same way spoken dialogue moves into a talky song verse before emerging as a great tune. Here, as at the Ascot races, a stage convention—the autonomy of dance as an expressive art form—is valued over conventional filmic naturalism. Shot on location in New York City using the fastest color film stocks and most advanced compact sound and camera equipment of the day, artistically executed mostly

by New Yorkers,

West Side Story

was both grittier and artier than almost any contemporary Hollywood film made in beautiful sunny California.