Escape from North Korea (42 page)

Read Escape from North Korea Online

Authors: Melanie Kirkpatrick

Kim Jong Il had a dream. In it, the late leader of North Korea saw himself being stoned to death. The first rocks were thrown by Americans. Then came a hail of stones from the Americans' South Korean lackeys. Finally the nightmare reached its terrifying crescendo as North Koreans themselves lined up to pummel their leader. It was every dictator's nightmare: being deposed by his own people, who rose up against him.

Kim Jong Il divulged his dream to Chung Jun-yung, the late founder of the Hyundai Group, the South Korean car maker, who was a frequent visitor to Pyongyang during the years of the Sunshine Policy. The tycoon's son, Chung Mong-joon, a South Korean politician and onetime presidential candidate, recounted that story on television in early 2011 after his father's death. “My father met Kim Jong Il many times and had lengthy conversations with him over meals,” the younger Chung explained. “Kim once said, âMany people come to greet me wherever I go, but I know that they don't like me.' ”

8

8

Call it the Ceausescu effect. Defectors who moved in Kim Jong Il's orbit before they fled North Korea express the view that the late dictator was terrified he would suffer the same fate as that of Nicolae Ceausescu, the longtime strongman of Communist Romania and, like the North Korean dictator, the subject of a bizarre personality cult. On Christmas Day in 1989, a few weeks after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Romanians rose up against Ceausescu and his wife, Elena. The couple was arrested, tried, and convicted of a range of capital offenses, including genocide against their fellow Romanians. The death sentence was carried out immediately. Just as North Koreans lined up in Kim Jong Il's dream to stone him to death, hundreds

of Romanians volunteered to take a spot on the firing squad that killed their detested dictator.

of Romanians volunteered to take a spot on the firing squad that killed their detested dictator.

The collapse of Communism in Europe took place with dazzling speed. So, too, it could happen in North Korea, which in any case is moving toward a denouement after the death in December 2011 of Kim Jong Il. His son and heir, Kim Jong Eun, is green, untested, and widely distrusted. Like his father, Kim Jong Eun is said to fear that his own people will kill him. In the younger Kim's case, it is the example of what happened to Libya's Moammar Gadhafi that is the stuff of nightmares. Gadhafi died at the hands of Libyan rebels in the democratic uprising of 2011, a few months before Kim Jong Eun became North Korea's supreme leader. His bloody final moments were captured on a grainy cellphone video that sped around the Web, presumably even reaching the computer screen of Kim Jong Eun in Pyongyang. The Libyan strongman was pulled from his hiding place in a drainage pipe and battered by an angry mob before being shot by a young man wearing a Yankees cap.

The new underground railroad has set in motion forces that are transforming North Korea and that may ultimately prove politically destabilizing. As we saw in Eastern Europe twenty years ago and in North Africa and the Middle East during the Arab Spring of our own decade, oppressed people can rise up with incredible speed to challenge even seemingly entrenched dictatorships. South Korea needs to be ready to jump at the chance of reunification, and the rest of the world needs to be ready to help.

No one wants to exercise a military option with North Korea. War games show that the West would emerge victorious, but at great cost of human life on both sides of the DMZ. How much better it would be to adopt policies encouraging an outflow of North Koreans who can then educate their friends and family left behind. Working from outside, these émigrés can spur internal pressures for change.

In trying to restrain a belligerent North Korea, the world speaks of sanctions and even manages to enforce them once in a whileâto

little or no effect. Meanwhile an effective way to pressure the murderous Pyongyang regime is largely overlooked: its own people. As yet, there is no organized dissent in North Korea. But thanks to the new underground railroad, awareness is growing among ordinary North Koreans of the world outside their country's borders. They have an increasing skepticism, disdain even, of the regime that denies them the freedoms and prosperity that exist elsewhere.

little or no effect. Meanwhile an effective way to pressure the murderous Pyongyang regime is largely overlooked: its own people. As yet, there is no organized dissent in North Korea. But thanks to the new underground railroad, awareness is growing among ordinary North Koreans of the world outside their country's borders. They have an increasing skepticism, disdain even, of the regime that denies them the freedoms and prosperity that exist elsewhere.

Joseph Gwang-jin Kim, the boy who fled North Korea by walking across the frozen Tumen River on the eve of Kim Jong Il's birthday in 2005, spoke in Manhattan about his escape. He addressed a group of Americans funding the new underground railroad. Speaking in English, he thanked them for their support of him and his countrymen. “What you are doing changed my life,” Joseph told his benefactors. Then he added, “and it will eventually change North Korea.”

Kang Su-min, a North Korean woman now living in Seoul after years on the run in China, is similarly optimistic. She likes to say that most of her fellow exiles look to the future, not the past. They focus not on what their nation is today but what it may become tomorrow.

North Korea is the modern world's most repressive state. One day that will change. Meanwhile, the escape to freedom of a small number of its people is a rare good-news story that foretells a happier future for that sad country.

Â

Possessing a Bible is a crime in North Korea. This New Testament, published in the early twentieth century, was smuggled out of North Korea by a Christian whose family had hidden it for more than half a century. (Courtesy of Open Doors USA)

Â

North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung greets American evangelist Billy Graham during Graham's visit to Pyongyang in 1994. (Courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association)

Â

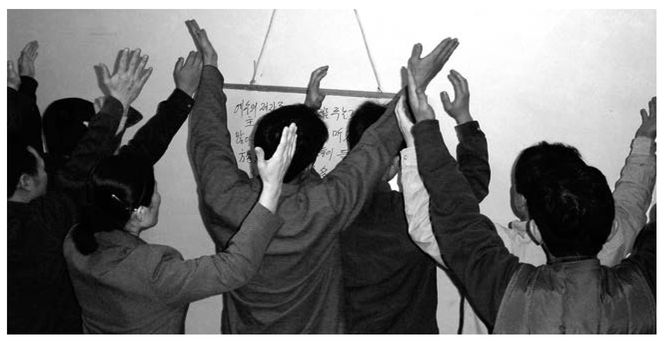

North Korean refugees worship secretly in China. (Courtesy of Open Doors USA)

Â

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld unveils a satellite photograph of the Korean Peninsula at night at a Pentagon news conference in 2006. (Robert Ward/ Department of Defense)

Â

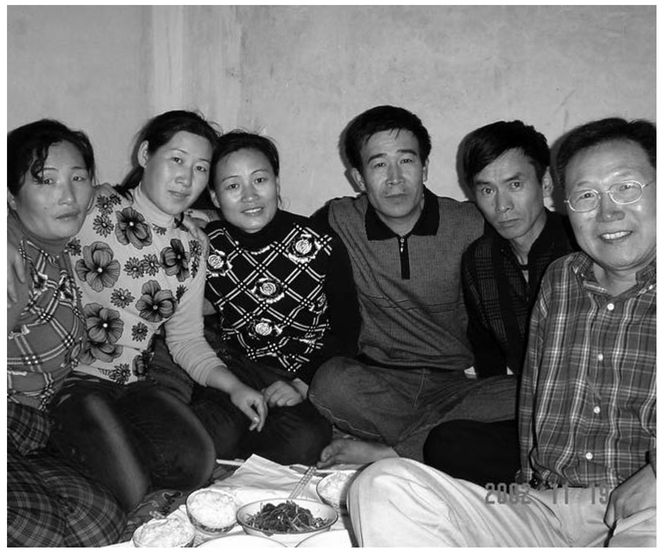

American Steve Kim (far right) and a group of North Korean refugees whom he sheltered in Guangdong Province in southern China. (Courtesy of 318 Partners Mission Foundation)

Â

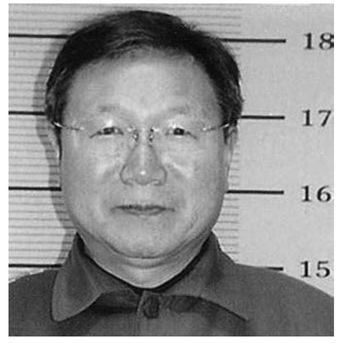

Mug shot of Steve Kim, taken by Chinese police after his arrest in 2003 for the crime of helping North Korean refugees. (Courtesy of 318 Partners Mission Foundation)

Â

Steve Kim (circled) in formation in the yard of the Chinese prison where he spent four years. (Courtesy of 318 Partners Mission Foundation)

Other books

Lock and Load by Desiree Holt

Dead Red Cadillac, A by Dahlke, R. P.

Seeker of Stars: A Novel by Fish, Susan

Hallowe'en Party by Agatha Christie

Tips on Having a Gay (ex) Boyfriend by Carrie Jones

Singing in the Shrouds by Ngaio Marsh

City of Darkness and Light by Rhys Bowen

Sydney Harbour Hospital: Tom's Redemption by Fiona Lowe