Essence and Alchemy (18 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

An Octave of Odors The Art of Composition

In the kingdom of smells, everything is either bliss or torture, sometimes so subtly blended that often I find myself, when the many strands of a supposedly simple odor are trapped in my palpitating nostrils, actually listening to it, as carefully as if I were unraveling a symphony's sonorous phrases.

â

Colette, “Fragrance”

86

Colette, “Fragrance”

86

85

85I

WAS STRUCK by the paradox implicit in a recent issue of

National Geographic

87

that was devoted to perfume. The sumptuous photographs that accompanied the article, page after page, were of natural perfume ingredients and raw materialsâfor example, a lush two-page spread in which “dew-kissed petals of damask roses spill from practiced fingers in Bulgaria's Valley of Roses.” The process the article explored, howeverâthe search for a custom perfumeâseemed to have nothing much to do with the materials depicted. Instead, the author responded to a series of questions about her style and self-image (Yves St. Laurent, not Christian Lacroix; red wine over white). Her answers, she explained, would be distilled into what is known in the perfume business as a brief, a précis of the perfume's concept (“A fragrance that does not shout. Elegant, crisp, sophisticated”) and target customer (“Generation X,

ladies who lunch, or, in this case, me”). For the article, each of five perfumers vied to create a scent for her. If she had been a brand name like Christian Dior in search of a new perfume product, the competitors would have been rival perfume suppliers, such as International Flavors and Fragrances or Quest International.

I've had an opportunity to observe how a well-respected perfumer does his creative work at one of the big fragrance houses in New York City. We gave each other the problem of building a perfume around a certain natural essence. I assigned him Tasmanian boronia, the staggeringly beautiful raspberry-toned floral, and he assigned me cinnamon, with the caveat “No potpourri.” He was referring to cinnamon's spicy ubiquitousness in bowls of dried herbs and spices that appear around the holidays.

As I have mentioned, cinnamon is an extremely difficult scent to work with because it is so strongly associated with certain foods and holidays. It is difficult to wrest free from those associations so that its warm spiciness can be smelled anew. Nor is cinnamon a scent of which I am particularly fond, so I found my assignment very challenging

indeed. I decided to make its sharp, sweet, woody, and spicy odor compete against essences that were equally as strong, like ambrette, clove, green pepper, and castoreum. To stand up to the intensity of these powerful personalities, I decided on a vanilla-scented base note and a full-bodied and sweet floral heart. I blended from the bottom up, figuring out the proportions as I went.

indeed. I decided to make its sharp, sweet, woody, and spicy odor compete against essences that were equally as strong, like ambrette, clove, green pepper, and castoreum. To stand up to the intensity of these powerful personalities, I decided on a vanilla-scented base note and a full-bodied and sweet floral heart. I blended from the bottom up, figuring out the proportions as I went.

After thinking for a while, the commercial perfumer simply wrote down a list of essences with numbers in front of them: 5 ml geranium, 3 ml oakmoss, 6 ml lemon, and so on. He had planned out, in his head, what essences would go into the blend, and exactly how much of each. The formula was given to a technician, who followed it exactly to assemble an undiluted perfume oil; this oil was then mixed with perfume alcohol in a 12 percent solution.

The process allowed for no response to the evolving shape of the perfume, no firsthand, drop-by-drop experience of how the oils were interacting with one another or with the alcohol. Of course, the behavior of synthetics is more precise and predictable, which makes it possible to work with them in a more “scientific” way. And in order to make perfumes in substantial quantities, some reliance on formula is necessary. But a process that is so abstract from the outset strikes me as unromantic and antithetical to the primal, hands-on sensuality that is inherent in the materials themselves.

From my research, I discovered that even after the advent of a mass-market perfume industry, the methods of commercial perfumers were not always so clinical. Jean Carles, who created such trend-setting and wildly successful perfumes of the thirties as the unisex fragrance Canoe and the Schiaparelli perfume Shocking, recalled of his own apprenticeship:

In my early days

88

on this rugged pathway, I found myself in the presence of tutors who seemed to have disregarded the necessity for basic rules and whose interest in our futures was

of the mildest. Watching how they proceeded with their own work did not make it seem particularly absorbing: they appeared to believe in a happy-go-lucky way of life, desultorily dipped smelling blotters into the available samples of odorous materials, and thus their formulations progressed, small addition by small addition, and not according to some preestablished plan. Thus in the past, most of the great perfume creations, or rather, of the commercially successful perfumes, were produced almost by chance, sometimes to the unfeigned surprise of their originators!

88

on this rugged pathway, I found myself in the presence of tutors who seemed to have disregarded the necessity for basic rules and whose interest in our futures was

of the mildest. Watching how they proceeded with their own work did not make it seem particularly absorbing: they appeared to believe in a happy-go-lucky way of life, desultorily dipped smelling blotters into the available samples of odorous materials, and thus their formulations progressed, small addition by small addition, and not according to some preestablished plan. Thus in the past, most of the great perfume creations, or rather, of the commercially successful perfumes, were produced almost by chance, sometimes to the unfeigned surprise of their originators!

Yet while “such happy occurrences are always possible,” Carles nevertheless cautions, “a firm belief in them should not be the guiding rule.”

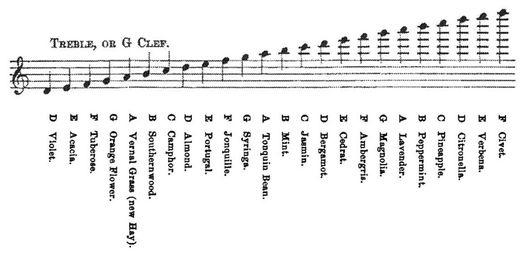

Even in their more austere traditions, classical perfumers did acknowledge that a perfume oil is not a single scent but a complexity of scents that interact with one another in unpredictable ways, the equivalent of notes to a musician or color to a painter. In fact, the great perfumers, like Edmond Roudnitska and Jean Carles, considered an understanding of philosophy and music, with its complex intellectual acrobatics, central to the making of perfume. Few went as far as Septimus Piesse, who in his seminal

The Art of Perfumery

(1867) described an octave of odors: A = tonka bean, B = mint, C = jasmine, and so on up the scale. But perfumers did develop the habit of translating the art of perfume-blending into the language of base, middle, and top notes and chords, on the basis of their relative volatility.

The Art of Perfumery

(1867) described an octave of odors: A = tonka bean, B = mint, C = jasmine, and so on up the scale. But perfumers did develop the habit of translating the art of perfume-blending into the language of base, middle, and top notes and chords, on the basis of their relative volatility.

Perfume manufactory, Nice

“The Gamut of Odors,” according to Septimus Piesse

And just as perfumers invoked music as a metaphor for perfume, artists, musicians, and writers did not hesitate to invoke perfume as a metaphor for the fundamental synesthesia of aesthetic response, which we experience when one sensation conjures up anotherâfor example, when hearing a certain sound evokes a particular color. As Guy de Maupassant

89

wrote, “On hearing that sonata, I could no longer tell whether I was breathing music or listening to scent. For the sounds, colors and smells do not answer one another in nature only, but in ourselves they are blended at times into a profound unity, drawing different responses from different organs.”

89

wrote, “On hearing that sonata, I could no longer tell whether I was breathing music or listening to scent. For the sounds, colors and smells do not answer one another in nature only, but in ourselves they are blended at times into a profound unity, drawing different responses from different organs.”

The linking of scent with sound and color has long historical

roots. In

Fragrant and Radiant Symphony,

the twentieth-century British metaphysical writer Roland Hunt traces it through a long, glorious, and often mystical tradition

90

to the funeral practices of the Egyptian kings, who “took with them to their tombs particular perfumes, colorful raiment, and musical instruments against the day when they would awaken to attune these vibrant things in resplendent symphony.” But no one has captured the experience of synesthesia more eloquently than Baudelaire:

roots. In

Fragrant and Radiant Symphony,

the twentieth-century British metaphysical writer Roland Hunt traces it through a long, glorious, and often mystical tradition

90

to the funeral practices of the Egyptian kings, who “took with them to their tombs particular perfumes, colorful raiment, and musical instruments against the day when they would awaken to attune these vibrant things in resplendent symphony.” But no one has captured the experience of synesthesia more eloquently than Baudelaire:

Some perfumes are as fragrant

91

as an infant's flesh,

Sweet as an oboe's cry, and greener than the spring.

91

as an infant's flesh,

Sweet as an oboe's cry, and greener than the spring.

Synthesthesia is based on a profound harmony among the senses themselves, which has its parallel point of convergence in the imagination. I like to be reminded of this fundamental identity of the senses as I work with scent, which is one of the reasons why I not only don't mind but enjoy using those essential oils that are beautifully hued and color perfume in a jewel-like fashion. There is nothing more simple and mysterious than the sight of a drop of indigo-blue chamomile wending its way through a beaker of clear perfume alcohol, like a skywriter in a parallel universe. If you would like to experiment with color in perfume, here are some essences and hues to consider:

Reddish orange

: rose absolute, patchouli

: rose absolute, patchouli

Orange

: boronia, orange flower absolute, tagetes

: boronia, orange flower absolute, tagetes

Yellow

: orange, ylang ylang concrete, lemon

: orange, ylang ylang concrete, lemon

Green

: vetiver, violet leaf, green tea, clary sage concrete

: vetiver, violet leaf, green tea, clary sage concrete

Turquoise:

lavender absolute

lavender absolute

Dark blue

: German chamomile

: German chamomile

Brownish green:

oakmoss, osmanthus

oakmoss, osmanthus

Amber

: tuberose, jasmine, benzoin, champa

: tuberose, jasmine, benzoin, champa

Brown

: vanilla, tolu balsam, Peru balsam, labdanum, hay, blond tobacco

: vanilla, tolu balsam, Peru balsam, labdanum, hay, blond tobacco

N

otwithstanding commercial perfumers' sophisticated understanding of the unruly, intricate, overlapping nature of sensation, the standardized methods that evolved among them in the twentieth century relied heavily on intellectual abstractionâon the ability of imagination to divorce itself from direct sensory input or to feed upon it long after the fact. Even Roudnitska says:

otwithstanding commercial perfumers' sophisticated understanding of the unruly, intricate, overlapping nature of sensation, the standardized methods that evolved among them in the twentieth century relied heavily on intellectual abstractionâon the ability of imagination to divorce itself from direct sensory input or to feed upon it long after the fact. Even Roudnitska says:

When the composer writes

92

down a formula, his composition is not based on sensation but on the memory of sensations, in other words on abstractions of abstractions ⦠We work with these abstract forms by making an effort to evoke and combine them in thought ⦠All the various “prerequisites” have been mobilized and whisper the first elements which could correspond to our imagined form. We start by writing names in columns, in a sequence which is dictated, above all ⦠by the fact that its tonality seems necessary for the envisaged construction. All our ideas land on the paper in a variety of forms which initially add to our general confusion but finally result in our idea of a perfume.

92

down a formula, his composition is not based on sensation but on the memory of sensations, in other words on abstractions of abstractions ⦠We work with these abstract forms by making an effort to evoke and combine them in thought ⦠All the various “prerequisites” have been mobilized and whisper the first elements which could correspond to our imagined form. We start by writing names in columns, in a sequence which is dictated, above all ⦠by the fact that its tonality seems necessary for the envisaged construction. All our ideas land on the paper in a variety of forms which initially add to our general confusion but finally result in our idea of a perfume.

Other books

Mind Games by Hilary Norman

Born of Persuasion by Jessica Dotta

Earthfall (Homecoming) by Orson Scott Card

To Charm A Billionaire (Men of Monaco Book 1) by Michelle Monkou

To Walk Far, Carry Less : Camino de Santiago by Ashmore, Jean-Christie

Aftermath by Tim Marquitz

Hunted by Darkness (Darkness #4) by Katie Reus

That God Won't Hunt by Sizemore, Susan

Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier by Tyson, Neil deGrasse, Avis Lang

Heart of Darkness and The Secret Sharer by Joseph Conrad