Everything Bad Is Good for You (13 page)

Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

Probing the limits of the game physics is another oft-ignored facet of gaming culture. I suspect most hard-core gamers would acknowledge that part of the pleasure of their immersions comes from this kind of pursuit, searching out the points where the system shows its flawsâpartially because those flaws can be exploited, as in

PacMan

's patterns, but also because there's something strangely satisfying about defining the edges of a simulation, learning what it's capable of and where it breaks down. Some people find this kind of exploration appealing in ordinary life: they're the sort that actually enjoys looking under the hood of the car, or memorizing UNIX commands. But video games

force

you to speculate about what's going on under the hood. If you don't think about the underlying mechanics of the simulationâeven if that thinking happens in a semiconscious wayâyou won't last very long in the game. You have to probe to progress.

I didn't have a word for it at the time, of course, but I now realize that my tour through the universe of dice-baseball was a way of probing the physics of those early games. I'd learn the explicit rules for each simulation, but the really fascinating moment came when I'd start rolling the dice and generating results. Only by playing the simulations could you get a sense of their realism. Usually, you had to work through a quarter of a season before the imperfections would reveal themselves: batters would strike out too frequently in one simulation; another would allow sluggers to average an implausible two home runs a game. I was detecting flaws in these systems, but there was nonetheless something profoundly satisfying about the experience. Bringing these imperfections to light felt like solving a mystery, looking past the surface illusion of player cards and charts to the inner truth of the system.

Â

O

NE OF

the best ways to grasp the cognitive virtues of gameplaying is to ask committed players to describe what's going on in their heads halfway through a long virtual adventure like

Zelda

or

Half-Life.

It's crucial here not to ask what's happening in the gameworld, but rather what's happening to the players mentally: what problems they're actively working on, what objectives they're trying to achieve. In my experience, most gamers will be more inclined to show rather than tell the probing they've done; they'll have internalized flaws or patterns in the simulation without being fully aware of what they're doing. Certain strategies just

feel

right.

But if the gamers' probing is semiconscious, their awareness of mid-game

objectives

will be crystal clear. They'll be able to give you an explicit account of what they need to do to reach the goals that the game has laid out for them. Many of these goals will have been obscure in the opening sequences of the game, but by the halfway point, players have usually constructed a kind of to-do list that governs their strategy. If probing is all about depth, exploring the buried logic of the simulation, tracking objectives is a kind of temporal thinking, a looking forward to all the hurdles that separate you from the game's completion.

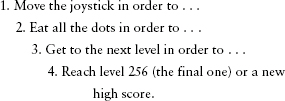

Tracking objectives seems simple enough. If you stopped playing in the early nineties, or if you only know about games from secondhand accounts, you'd probably assume that the mid-game objectives would sound something like this: Shoot that guy over there! Or: Avoid the blue monsters! Or: Find the magic key!

But interrupt a player in the middle of a

Zelda

quest, and ask her what her objectives are, and you'll get a much more interesting answer. Interesting for two reasons: first, the sheer number of objectives simultaneously at play; and second, the nested, hierarchical way in which those objectives have to be mentally organized. For comparison's sake, here's what the state of mind of a

PacMan

player would look like mid-game circa 1981:

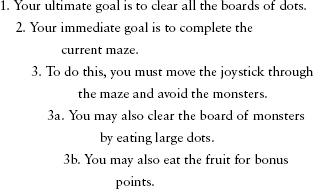

Those objectives could be mildly complicated with the addition of one subcategory, which would look like this:

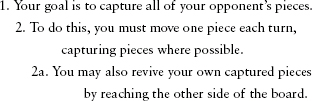

A real-world game like checkers would generate a list of comparable simplicity:

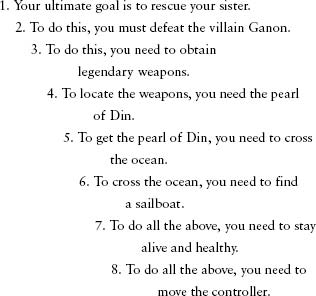

A map of the objectives in the latest

Zelda

game,

The Wind Waker,

looks quite different:

The eight items can be divided into two groups, each with a slightly different purchase on the immediate present. The last two items (7 and 8) are almost metabolic in nature, the basics of virtual self-preservation: keep your character alive, with maximum power and, where possible, flush with cash. Like many core survival behaviors, some of these objectives take quite a bit of trainingâlearning the navigation interface and mapping it onto the controller, for instanceâbut once you've mastered them, you don't necessarily have to think about what you're doing. You've internalized or automated the knowledge, just as you did years ago when you learned how to run or climb or talk.

Beyond the horizon of those immediate needs lie the six remaining master objectives. These are forward projections that color the immediate present. They're like constellations guiding your ship through uncertain waters. Lose sight of them and you're adrift.

But those master objectives are rarely the player's central focal point, because most of the game is spent solving smaller problems that stand in the way of achieving one of the primary goals. In this sense, our list of eight nested objectives is a gross simplification of the actual problem-solving that goes on in a game like

Zelda.

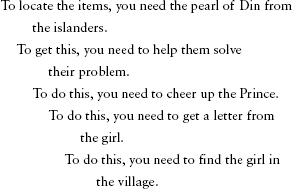

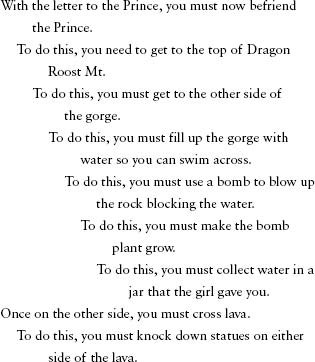

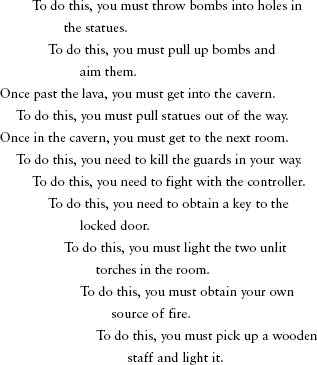

Zoom in on just one of these objectivesâfinding the pearl of Dinâand the list of objectives running through the player's mind would look something like this:

I'll spare you the entire sequence for this one objective, which would continue on for another page unabridged. And remember, this is merely a snapshot of an hour or so of play from a title that averages around forty hours to complete. And remember, too, that almost all of these objectives have to be deciphered by the player on his own, assuming he's not consulting a game guide. These local objectives make up the primary texture of the game; they're what you spend most of your time working through. Gamers sometimes talk about the units formed by these steps as a “puzzle.” You hit a point in the game where you know you need to do something, but there's some obstruction in your way, and the game conventions signal to you that you've encountered a puzzle. You're not lost, or confused; in fact, you're on precisely the right trackâit's just the game designers have artfully deposited a puzzle in the middle of that track.

I call the mental labor of managing all these simultaneous objectives “telescoping” because of the way the objectives nest inside one another like a collapsed telescope. I like the term as well because part of this skill lies in focusing on immediate problems while still maintaining a long-distance view. You can't progress far in a game if you simply deal with the puzzles you stumble across; you have to coordinate them with the ultimate objectives on the horizon. Talented gamers have mastered the ability to keep all these varied objectives alive in their heads simultaneously.