Everything Bad Is Good for You (14 page)

Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

Telescoping should not be confused with multitasking. Holding this nested sequence of interlinked objectives in your mind is not the same as the classic multitasking teenager scenario, where they're listening to their iPod while instant messaging their friends and Googling for research on a term paper. Multitasking is the ability to handle a chaotic stream of unrelated objectives. Telescoping is all about order, not chaos; it's about constructing the proper hierarchy of tasks and moving through the tasks in the correct sequence. It's about perceiving relationships and determining priorities.

If telescoping involves a sequence, by the same token the feeling it conjures in the brain is not, I think, a

narrative

feeling. There are layers to narratives, to be sure, and they inevitably revolve around a mix of the present and future, between what's happening now and the tantalizing question of where it's all headed. But narratives are built out of events, not tasks. They happen

to

you. In the gameworld you're forced to define and execute the tasks; if your definitions get blurry or are poorly organized, you'll have trouble playing. You can still enjoy a book without explicitly concentrating on where the narrative will take you two chapters out, but in gameworlds you need that long-term planning as much as you need present-tense focus. In a sense, the closest analog to the way gamers are thinking is the way programmers think when they write code: a nested series of instructions with multiple layers, some focused on the basic tasks of getting information in and out of memory, some focused on higher-level functions like how to represent the program's activity to the user. A program is a sequence, but not a narrative; playing a video game generates a series of events that retrospectively sketch out a narrative, but the pleasures and challenges of playing don't equate with the pleasures of following a story.

There is something profoundly

lifelike

in the art of probing and telescoping. Most video games take place in worlds that are deliberately fanciful in nature, and even the most realistic games can't compare to the vivid, detailed illusion of reality that novels or movies concoct for us. But our lives are not stories, at least in the present tenseâwe don't passively consume a narrative thread. (We turn our lives into stories after the fact, after the decisions have been made, and the events have unfolded.) But we do probe new environments for hidden rules and patterns; we do build telescoping hierarchies of objectives that govern our lives on both micro and macro time frames. Traditional narratives have much to teach us, of course: they can enhance our powers of communication, and our insight into the human psyche. But if you were designing a cultural form explicitly to train the cognitive muscles of the brain, and you had to choose between a device that trains the mind's ability to follow narrative events, and one that enhanced the mind's skills at probing and telescopingâwell, let's just say we're fortunate not to have to make that choice.

Still, I suspect that some readers may be cringing at the subject matter of those

Zelda

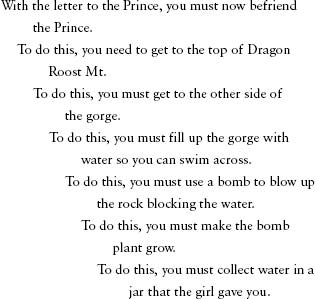

objectives. Here again, the problem lies in adopting aesthetic standards designed to evaluate literature or drama in determining whether we should take the video games seriously. Consider this sequence from our telescoping inventory:

If you approach this description with aesthetic expectations borrowed from the world of literature, the content seems at face value to be child's play: blowing up bombs to get to Dragon Roost Mountain; watering explosive plants. A high school English teacher would look at this and say: There's no psychological depth here, no moral quandaries, no poetry. And he'd be right! But comparing these games to

The Iliad

or

The Great Gatsby

or

Hamlet

relies on a false premise: that the intelligence of these games lies in their content, in the themes and characters they represent. I would argue that the cognitive challenges of videogaming are much more usefully compared to another educational genre that you will no doubt recall from your school days:

Simon is conducting a probability experiment. He randomly selects a tag from a set of tags that are numbered from 1 to 100 and then returns the tag to the set. He is trying to draw a tag that matches his favorite number, 21. He has not matched his number after 99 draws.

What are the chances he will match his number on the 100th draw?

A. 1 out of 100

B. 99 out of 100

C. 1 out of 1

D. 1 out of 2

Judged by the standards employed by our English teacher, this passageâtaken from the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment exam for high-school mathâwould be an utter failure. Who is this Simon? We know nothing about him; he is a cipher to us, a prop. There are no flourishes in the prose, nothing but barren facts, describing a truly useless activity. Why would anyone want to number a hundred tags and then go about trying to randomly select a favorite number? What is Simon's motivation?

Word problems of this sort have little to offer in the way of moral lessons or psychological depth; they won't make students more effective communicators or teach them technical skills. But most of us readily agree that they are good for the mind on some fundamental level: they teach abstract skills in probability, in pattern recognition, in understanding causal relations that can be applied in countless situations, both personal and professional. The problems that confront the gamers of

Zelda

can be readily translated into this form, and indeed in translating a core property of the experience is revealed:

You need to cross a gorge to reach a valuable destination. At one end of the gorge a large rock stands in front of a river, blocking the flow of water. Around the edge of the rock a number of small flowers are growing. You have been given a jar by another character. How can you cross the gorge?

- Jump across it.

- Carry small pails of water from the river and pour them in the gorge, and then swim across.

- Water the plants, and then use the bombs they grow to blow up the rock, releasing the water, and then swim across.

- Go back and see if you've missed some important tool in an earlier scene.

Again, the least interesting thing about this text is the substance of the story. You could perhaps meditate on the dramatic irony inherent in bomb-growing flowers, or analyze the gift economy relationship introduced with the crucial donation of the jar. But those interpretations will go only so far, because what's important here is not the content of the

Zelda

world, but the way that world has been organized to tax the problem-solving skills of the player. To be sure, the pleasure of gaming goes beyond this kind of problem-solving; the objects and textures of the worlds offer rich aesthetic experiences; many networked games offer intriguing social exchanges; increasingly the artificial intelligence embedded in some virtual characters provides amazing interactions. But these are all ultimately diversions. You can't make progress in the game without learning the rules of the environment. On the simplest level, the

Zelda

player learns how to grow bombs out of flowers. But the collateral learning of the experience offers a far more profound reward: the ability to probe and telescope in difficult and ever-changing situations. It's not

what

the player is thinking about, but the

way

she's thinking.

At first glance, it might be tempting to connect the complexity of video games with the more familiar idea of “information overload” associated with the rise of electronic media. But a crucial difference exists. Information overload is a kind of backhanded compliment you'll often hear about today's culture: there's too much data flowing into our lives, but at least we're getting better at managing that data-stream, even if we may be approaching some kind of threshold point where our senses will simply be overwhelmed. This is a quantitative argument, not a qualitative one. It's nice to be able to watch TV, talk on the phone, and read your e-mail all at the same time, but it's a superficial skill, not a deep one. It usually involves skimming the surface of the incoming data, picking out the relevant details, and moving on to the next stream. Multimedia pioneer Linda Stone has coined a valuable term for this kind of processing: continuous partial attention. You're paying attention, but only partially. That lets you cast a wider net, but it also runs the risk of keeping you from really studying the fish.

Probing and telescoping represent anotherâequally importantâtendency in the culture: the emergence of forms that encourage participatory thinking and analysis, forms that challenge the mind to make sense of an environment, not just play catch-up with the acceleration curve. I think for many people who do not have experience with them, games seem like an extension of the rapid-fire visual editing techniques pioneered by MTV twenty years ago: a seismic increase in images-per-second without a corresponding increase in analysis or sense-making. But the reality of MTV visuals is not that the eye learns to interpret all the images as they fly by, perceiving new relationships between them. Instead, the eye learns to tolerate chaos, to experience disorder as an aesthetic experience, the way the ear learned to appreciate distortion in music a generation before. To non-players, games bear a superficial resemblance to music videos: flashy graphics; the layered mix of image, music, and text; the occasional burst of speed, particularly during the pre-rendered opening sequences. But what you actually

do

in playing a gameâthe way your mind has to workâis radically different. It's not about tolerating or aestheticizing chaos; it's about finding order and meaning in the world, and making decisions that help create that order.

ELEVISION

T

HE INTERACTIVE NATURE

of games means that they will inevitably require more decision-making than passive forms like television or film. But popular television showsâand to a slightly lesser extent, popular filmsâhave also increased the cognitive work they demand from their audience, exercising the mind in ways that would have been unheard of thirty years ago. For someone loosely following the debate over the medium's cultural impact, the idea that television is actually improving our minds will sound like apostasy. You can't surf the Web or flip through a newsstand for more than a few minutes without encountering someone complaining about the surge in sex and violence on TV: from Tony Soprano to Janet Jackson. There's no questioning that the trend is real enough, though it is as old as television itself. In Newton Minow's famous “vast wasteland” speech from 1961, he described the content of current television programming as a “procession ofâ¦blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder”âthis in the era of Andy Griffith, Perry Como, and Uncle Miltie. But evaluating the social merits of any medium and its programming can't be limited purely to questions of subject matter. There was nothing particularly redeeming in the subject matter of my dice baseball games, but they nonetheless taught me how to think in powerful new ways. So if we're going to start tracking swear words and wardrobe malfunctions, we ought to at least include another line in the graph: one that charts the cognitive demands that televised narratives place on their viewers. That line, too, is trending upward at a dramatic rate.

Television may be more passive than video games, but there are degrees of passivity. Some narratives force you to do work to make sense of them, while others just let you settle into the couch and zone out. Part of that cognitive work comes from following multiple threads, keeping often densely interwoven plotlines distinct in your head as you watch. But another part involves the viewer's “filling in”: making sense of information that has been either deliberately withheld or deliberately left obscure. Narratives that require that their viewers fill in crucial elements take that complexity to a more demanding level. To follow the narrative, you aren't just asked to remember. You're asked to analyze. This is the difference between intelligent shows, and shows that force you to be intelligent. With many television classics that we associate with “quality” entertainmentâ

Mary Tyler Moore, Murphy Brown, Frasier

âthe intelligence arrives fully formed in the words and actions of the characters onscreen. They say witty things to each other, and avoid lapsing into tired sitcom clichés, and we smile along in our living room, enjoying the company of these smart people. But assuming we're bright enough to understand the sentences they're sayingâfew of which are rocket science, mind you, or any kind of science, for that matterâthere's no intellectual labor involved in enjoying the show as a viewer. There's no filling in, because the intellectual achievement exists entirely on the other side of the screen. You no more challenge your mind by watching these intelligent shows than you challenge your body watching

Monday Night Football.

The intellectual work is happening onscreen, not off.

But another kind of televised intelligence is on the rise. Recall the cognitive benefits conventionally ascribed to reading: attention, patience, retention, the parsing of narrative threads. Over the last half century of television's dominance over mass culture, programming on TV has steadily increased the demands it places on precisely these mental faculties. The nature of the medium is such that television will never improve its viewers' skills at translating letters into meaning, and it may not activate the imagination in the same way that a purely textual form does. But for all the other modes of mental exercise associated with reading, television is growing increasingly rigorous. And the pace is acceleratingâthanks to changes in the economics of the television business, and to changes in the technology we rely on to watch.

This progressive trend alone would probably surprise someone who only read popular accounts of TV without watching any of it. But perhaps the most surprising thing is this: that the shows that have made the most demands on their audience have also turned out to be among the most lucrative in television history.

Â

P

UT ASIDE

for a moment the question of why the marketplace is rewarding complexity, and focus first on the question of what this complexity looks like. It involves three primary elements: multiple threading, flashing arrows, and social networks.

Multiple threading is the most acclaimed structural convention of modern television programming, which is ironic because it's also the convention with the most debased pedigree. According to television lore, the age of multiple threads began with the arrival of

Hill Street Blues

in 1981, the Steven Bochcoâcreated police drama invariably praised for its “gritty realism.” Watch an episode of

Hill Street Blues

side by side with any major drama from the preceding decadesâ

Starsky and Hutch,

for instance, or

Dragnet

âand the structural transformation will jump out at you. The earlier shows follow one or two lead characters, adhere to a single dominant plot, and reach a decisive conclusion at the end of the episode. Draw an outline of the narrative threads in almost every

Dragnet

episode and it will be a single line: from the initial crime scene, through the investigation, to the eventual cracking of the case. A typical

Starsky and Hutch

episode offers only the slightest variation on this linear formula: the introduction of a comic subplot that usually appears only at the tail ends of the episode, creating a structure that looks like the graph below. The vertical axis represents the number of individual threads, and the horizontal axis is time.

Starsky and Hutch

includes a few other twists: While both shows focus almost exclusively on a single narrative,

Dragnet

tells the story entirely from the perspective of the investigators.

Starsky and Hutch,

on the other hand, oscillates between the perspectives of the cops and that of the criminals. And while both shows adhere religiously to the principle of narrative self-containmentâthe plots begin and end in a single episodeâ

Dragnet

takes the principle to a further extreme, introducing the setting and main characters with Joe Friday's famous voice-over in every episode.

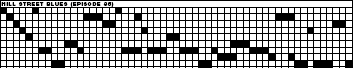

A

Hill Street Blues

episode complicates the picture in a number of profound ways. The narrative weaves together a collection of distinct strandsâsometimes as many as ten, though at least half of the threads involve only a few quick scenes scattered through the episode. The number of primary charactersâand not just bit partsâswells dramatically. And the episode has fuzzy borders: picking up one or two threads from previous episodes at the outset, and leaving one or two threads open at the end. Charted graphically, an average episode looks like this:

Critics generally cite

Hill Street Blues

as the origin point of “serious drama” native to the television mediumâdifferentiating the series from the single episode dramatic programs from the fifties, which were Broadway plays performed in front of a camera. But the

Hill Street

innovations weren't all that original; they'd long played a defining role in popular televisionâjust not during the evening hours. The structure of a

Hill Street

episodeâand indeed all of the critically acclaimed dramas that followed, from

thirtysomething

to

Six Feet Under

âis the structure of a soap opera.

Hill Street Blues

might have sparked a new golden age of television drama during its seven-year run, but it did so by using a few crucial tricks that

Guiding Light

and

General Hospital

had mastered long before.

Bochco's genius with

Hill Street

was to marry complex narrative structure with complex subject matter.

Dallas

had already shown that the extended, interwoven threads of the soap opera genre could survive the weeklong interruptions of a prime-time show, but the actual content of

Dallas

was fluff. (The most probing issue it addressed was the now folkloric question of who shot JR.)

All in the Family

and

Rhoda

showed that you could tackle complex social issues, but they did their tackling in the comfort of the sitcom living room structure.

Hill Street

had richly drawn characters confronting difficult social issues, and a narrative structure to match.

Since

Hill Street

appeared, the multithreaded drama has become the most widespread fictional genre on prime time:

St. Elsewhere, thirtysomething, L.A. Law, Twin Peaks, NYPD Blue, ER, The West Wing, Alias, The Sopranos, Lost, Desperate Housewives.

The only prominent holdouts in drama are shows like

Law & Order

that have essentially updated the venerable

Dragnet

format, and thus remained anchored to a single narrative line. Since the early eighties, there has been a noticeable increase in narrative complexity in these dramas. The most ambitious show on TV to dateâ

The Sopranos

âroutinely follows a dozen distinct threads over the course of an episode, with more than twenty recurring characters. An episode from late in the first season looks like this:

The total number of active threads equals the number of multiple plots of

Hill Street,

but here each thread is more substantial. The show doesn't offer a clear distinction between dominant and minor plots; each storyline carries its weight in the mix. The episode also displays a chordal mode of storytelling entirely absent from

Hill Street

: a single scene in

The Sopranos

will often connect to three different threads at the same time, layering one plot atop another. And every single thread in this

Sopranos

episode builds on events from previous episodes, and continues on through the rest of the season and beyond. Almost every sequence in the show connects to information that exists outside the frame of the current episode. For a show that spends as much time as it does on the analyst's couch,

The Sopranos

doesn't waste a lot of energy with closure.