Everything Bad Is Good for You (3 page)

Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

The forces at work in these systems operate on multiple levels: underlying changes in technology that enable new kinds of entertainment; new forms of online communications that cultivate audience commentary about works of pop culture; changes in the economics of the culture industry that encourage repeat viewing; and deep-seated appetites in the human brain that seek out reward and intellectual challenge. To understand those forces we'll need to draw upon disciplines that don't usually interact with one another: economics, narrative theory, social network analysis, neuroscience.

This is a story of trends, not absolutes. I do not believe that most of today's pop culture is made up of masterpieces that will someday be taught alongside Joyce and Chaucer in college survey courses. The television shows and video games and movies that we'll look at in the coming pages are not, for the most part, Great Works of Art. But they are more complex and nuanced than the shows and games that preceded them. While the Sleeper Curve maps

average

changes across the pop cultural landscapeâand not just the complexity of single worksâI have focused on a handful of representative examples in the interest of clarity. (The endnotes offer a broader survey.)

I believe that the Sleeper Curve is the single most important new force altering the mental development of young people today, and I believe it is largely a force for good: enhancing our cognitive faculties, not dumbing them down. And yet you almost never hear this story in popular accounts of today's media. Instead, you hear dire stories of addiction, violence, mindless escapism. “All across the political spectrum,” television legend Steve Allen writes in a

Wall Street Journal

op-ed, “thoughtful observers are appalled by what passes for TV entertainment these days. No one can claim that the warning cries are simply the exaggerations of conservative spoil-sports or fundamentalist preachersâ¦. The sleaze and classless garbage on TV in recent years exceeds the boundaries of what has traditionally been referred to as Going Too Far.” The influential Parents Television Council argues: “The entertainment industry has pushed the content envelope too far; television and films filled with sex, violence, and profanity send strong negative messages to the youth of Americaâmessages that will desensitize them and make for a far more disenfranchised society as these youths grow into adults.” And then there's syndicated columnist Suzanne Fields: “The television sitcom is emblematic of our culture; parents, no matter what their degree of education, have abandoned the simplest standard of shame. Their children literally âdo not know better.' The drip, drip, drip of the popular culture dulls our senses. An open society with high technology exposes increasing numbers of adults and children to the lowest common denomination of sex and violence.” You could fill an encyclopedia volume with all the kindred essays published in the past decade.

Exceptions to this dire assessment exist, but they are of the rule-proving variety. You'll see the occasional grudging acknowledgments of minor silver linings: an article will suggest that video games enhance visual memory skills, or a critic will hail

The West Wing

as the rare flowering of thoughtful programming in the junkyard of prime-time television. But the dominant motif is one of decline and atrophy: we're a nation of reality program addicts and Nintendo freaks. Lost in that account is the most interesting trend of all: that the popular culture has been growing increasingly complex over the past few decades, exercising our minds in powerful new ways.

But to see the virtue in this form of positive brainwashing, we need to begin by doing away with the tyranny of the morality play. When most op-ed writers and talk show hosts discuss the social value of media, when they address the question of whether today's media is or isn't good for us, the underlying assumption is that entertainment improves us when it carries a healthy message. Shows that promote smoking or gratuitous violence are bad for us, while those that thunder against teen pregnancy or intolerance have a positive role in society. Judged by that morality play standard, the story of popular culture over the past fifty yearsâif not five hundredâis a story of steady decline: the morals of the stories have grown darker and more ambiguous, and the anti-heroes have multiplied.

The usual counterargument here is that what media has lost in moral clarity it has gained in realism. The real world doesn't come in nicely packaged public service announcements, and we're better off with entertainment that reflects that fallen state with all its ethical ambiguity. I happen to be sympathetic to that argument, but it's not the one I want to make here. I think there is another way to assess the social virtue of pop culture, one that looks at media as a kind of cognitive workout, not as a series of life lessons. Those dice baseball games I immersed myself in didn't contain anything resembling moral instruction, but they nonetheless gave me a set of cognitive tools that I continue to rely on, nearly thirty years later. There may indeed be more “negative messages” in the mediasphere today, as the Parents Television Council believes. But that's not the only way to evaluate whether our television shows or video games are having a positive impact. Just as importantâif not

more

importantâis the kind of thinking you have to do to make sense of a cultural experience. That is where the Sleeper Curve becomes visible. Today's popular culture may not be showing us the righteous path. But it is making us smarter.

ART

O

NE

The student of media soon comes to expect the new media of any period whatever to be classed as pseudo by those who acquired the patterns of earlier media, whatever they may happen to be.

âM

ARSHALL

M

C

L

UHAN

Â

ELEVISION

T

HE INTERACTIVE NATURE

of games means that they will inevitably require more decision-making than passive forms like television or film. But popular television showsâand to a slightly lesser extent, popular filmsâhave also increased the cognitive work they demand from their audience, exercising the mind in ways that would have been unheard of thirty years ago. For someone loosely following the debate over the medium's cultural impact, the idea that television is actually improving our minds will sound like apostasy. You can't surf the Web or flip through a newsstand for more than a few minutes without encountering someone complaining about the surge in sex and violence on TV: from Tony Soprano to Janet Jackson. There's no questioning that the trend is real enough, though it is as old as television itself. In Newton Minow's famous “vast wasteland” speech from 1961, he described the content of current television programming as a “procession ofâ¦blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder”âthis in the era of Andy Griffith, Perry Como, and Uncle Miltie. But evaluating the social merits of any medium and its programming can't be limited purely to questions of subject matter. There was nothing particularly redeeming in the subject matter of my dice baseball games, but they nonetheless taught me how to think in powerful new ways. So if we're going to start tracking swear words and wardrobe malfunctions, we ought to at least include another line in the graph: one that charts the cognitive demands that televised narratives place on their viewers. That line, too, is trending upward at a dramatic rate.

Television may be more passive than video games, but there are degrees of passivity. Some narratives force you to do work to make sense of them, while others just let you settle into the couch and zone out. Part of that cognitive work comes from following multiple threads, keeping often densely interwoven plotlines distinct in your head as you watch. But another part involves the viewer's “filling in”: making sense of information that has been either deliberately withheld or deliberately left obscure. Narratives that require that their viewers fill in crucial elements take that complexity to a more demanding level. To follow the narrative, you aren't just asked to remember. You're asked to analyze. This is the difference between intelligent shows, and shows that force you to be intelligent. With many television classics that we associate with “quality” entertainmentâ

Mary Tyler Moore, Murphy Brown, Frasier

âthe intelligence arrives fully formed in the words and actions of the characters onscreen. They say witty things to each other, and avoid lapsing into tired sitcom clichés, and we smile along in our living room, enjoying the company of these smart people. But assuming we're bright enough to understand the sentences they're sayingâfew of which are rocket science, mind you, or any kind of science, for that matterâthere's no intellectual labor involved in enjoying the show as a viewer. There's no filling in, because the intellectual achievement exists entirely on the other side of the screen. You no more challenge your mind by watching these intelligent shows than you challenge your body watching

Monday Night Football.

The intellectual work is happening onscreen, not off.

But another kind of televised intelligence is on the rise. Recall the cognitive benefits conventionally ascribed to reading: attention, patience, retention, the parsing of narrative threads. Over the last half century of television's dominance over mass culture, programming on TV has steadily increased the demands it places on precisely these mental faculties. The nature of the medium is such that television will never improve its viewers' skills at translating letters into meaning, and it may not activate the imagination in the same way that a purely textual form does. But for all the other modes of mental exercise associated with reading, television is growing increasingly rigorous. And the pace is acceleratingâthanks to changes in the economics of the television business, and to changes in the technology we rely on to watch.

This progressive trend alone would probably surprise someone who only read popular accounts of TV without watching any of it. But perhaps the most surprising thing is this: that the shows that have made the most demands on their audience have also turned out to be among the most lucrative in television history.

Â

P

UT ASIDE

for a moment the question of why the marketplace is rewarding complexity, and focus first on the question of what this complexity looks like. It involves three primary elements: multiple threading, flashing arrows, and social networks.

Multiple threading is the most acclaimed structural convention of modern television programming, which is ironic because it's also the convention with the most debased pedigree. According to television lore, the age of multiple threads began with the arrival of

Hill Street Blues

in 1981, the Steven Bochcoâcreated police drama invariably praised for its “gritty realism.” Watch an episode of

Hill Street Blues

side by side with any major drama from the preceding decadesâ

Starsky and Hutch,

for instance, or

Dragnet

âand the structural transformation will jump out at you. The earlier shows follow one or two lead characters, adhere to a single dominant plot, and reach a decisive conclusion at the end of the episode. Draw an outline of the narrative threads in almost every

Dragnet

episode and it will be a single line: from the initial crime scene, through the investigation, to the eventual cracking of the case. A typical

Starsky and Hutch

episode offers only the slightest variation on this linear formula: the introduction of a comic subplot that usually appears only at the tail ends of the episode, creating a structure that looks like the graph below. The vertical axis represents the number of individual threads, and the horizontal axis is time.

Starsky and Hutch

includes a few other twists: While both shows focus almost exclusively on a single narrative,

Dragnet

tells the story entirely from the perspective of the investigators.

Starsky and Hutch,

on the other hand, oscillates between the perspectives of the cops and that of the criminals. And while both shows adhere religiously to the principle of narrative self-containmentâthe plots begin and end in a single episodeâ

Dragnet

takes the principle to a further extreme, introducing the setting and main characters with Joe Friday's famous voice-over in every episode.

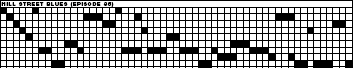

A

Hill Street Blues

episode complicates the picture in a number of profound ways. The narrative weaves together a collection of distinct strandsâsometimes as many as ten, though at least half of the threads involve only a few quick scenes scattered through the episode. The number of primary charactersâand not just bit partsâswells dramatically. And the episode has fuzzy borders: picking up one or two threads from previous episodes at the outset, and leaving one or two threads open at the end. Charted graphically, an average episode looks like this:

Critics generally cite

Hill Street Blues

as the origin point of “serious drama” native to the television mediumâdifferentiating the series from the single episode dramatic programs from the fifties, which were Broadway plays performed in front of a camera. But the

Hill Street

innovations weren't all that original; they'd long played a defining role in popular televisionâjust not during the evening hours. The structure of a

Hill Street

episodeâand indeed all of the critically acclaimed dramas that followed, from

thirtysomething

to

Six Feet Under

âis the structure of a soap opera.

Hill Street Blues

might have sparked a new golden age of television drama during its seven-year run, but it did so by using a few crucial tricks that

Guiding Light

and

General Hospital

had mastered long before.

Bochco's genius with

Hill Street

was to marry complex narrative structure with complex subject matter.

Dallas

had already shown that the extended, interwoven threads of the soap opera genre could survive the weeklong interruptions of a prime-time show, but the actual content of

Dallas

was fluff. (The most probing issue it addressed was the now folkloric question of who shot JR.)

All in the Family

and

Rhoda

showed that you could tackle complex social issues, but they did their tackling in the comfort of the sitcom living room structure.

Hill Street

had richly drawn characters confronting difficult social issues, and a narrative structure to match.

Since

Hill Street

appeared, the multithreaded drama has become the most widespread fictional genre on prime time:

St. Elsewhere, thirtysomething, L.A. Law, Twin Peaks, NYPD Blue, ER, The West Wing, Alias, The Sopranos, Lost, Desperate Housewives.

The only prominent holdouts in drama are shows like

Law & Order

that have essentially updated the venerable

Dragnet

format, and thus remained anchored to a single narrative line. Since the early eighties, there has been a noticeable increase in narrative complexity in these dramas. The most ambitious show on TV to dateâ

The Sopranos

âroutinely follows a dozen distinct threads over the course of an episode, with more than twenty recurring characters. An episode from late in the first season looks like this:

The total number of active threads equals the number of multiple plots of

Hill Street,

but here each thread is more substantial. The show doesn't offer a clear distinction between dominant and minor plots; each storyline carries its weight in the mix. The episode also displays a chordal mode of storytelling entirely absent from

Hill Street

: a single scene in

The Sopranos

will often connect to three different threads at the same time, layering one plot atop another. And every single thread in this

Sopranos

episode builds on events from previous episodes, and continues on through the rest of the season and beyond. Almost every sequence in the show connects to information that exists outside the frame of the current episode. For a show that spends as much time as it does on the analyst's couch,

The Sopranos

doesn't waste a lot of energy with closure.