Everything Bad Is Good for You (4 page)

Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

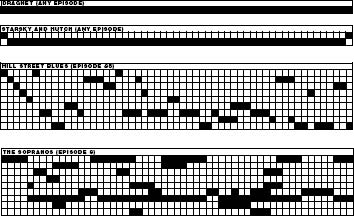

Put these four charts together and you have a portrait of the Sleeper Curve rising over the past thirty years of popular television.

In a sense, this is as much a map of cognitive changes in the popular mind as it is a map of onscreen developments, as though the media titans had decided to condition our brains to follow ever larger numbers of simultaneous threads. Before

Hill Street,

the conventional wisdom among television execs was that audiences wouldn't be comfortable following more than three plots in a single episode, and indeed, the first test screening of the

Hill Street

pilot in May 1980 brought complaints from the viewers that the show was too complicated. Fast forward twenty years and shows like

The Sopranos

engage their audiences with narratives that make

Hill Street

look like

Three's Company.

Audiences happily embrace that complexity because they've been trained by two decades of multithreaded dramas.

Is there something apples-to-oranges in comparing a boutique HBO program like

The Sopranos

to a network prime-time show like

Hill Street Blues

? Isn't the increase in complexity merely a reflection of the later show's smaller and more elite audience? I think the answer is no, for several reasons. First, measured by pure audience share,

The Sopranos

is a genuine national hit, regularly outdrawing network television shows in the same slot. Second,

Hill Street Blues

was itself a boutique showâthe first step in NBC's immensely successful attempt in the early eighties to target an upscale demographic instead of the widest possible audience. The show was a cultural and critical success, but it spent most of its life languishing in the mid-thirties in the Nielsen TV ratingsâand in its first season, the series finished eighty-third out of ninety-seven total shows on television. The total number of viewers for a

Sopranos

episode is not that different from that of an average episode of

Hill Street Blues,

even though the former's narrative complexity is at least twice that of the latter. (

The Sopranos

is even more complex on other scales, to which we will turn shortly.)

You can also measure the public's willingness to tolerate more complicated narratives in the success of shows such as

ER

or

24.

In terms of multiple threading, both shows usually follow around ten threads per episode, roughly comparable to

Hill Street Blues.

But

ER

and

24

are bona fide hits, regularly appearing in the Nielsen top twenty. In 1981, you could weave together three major narratives and a half dozen supporting plots over the course of an hour on prime time, and cobble together enough of an audience to keep the show safe from cancellation. Today you can challenge the audience to follow a more complicated mix, and build a juggernaut in the process.

Multithreading is the most celebrated structural feature of the modern television drama, and it certainly deserves some of the honor that has been doled out to it. When we watch TV, we intuitively track narrative-threads-per-episode as a measure of a given show's complexity. And all the evidence suggests that this standard has been rising steadily over the past two decades. But multithreading is only part of the story.

Â

A

FEW YEARS

after the arrival of the first-generation slasher moviesâ

Halloween, Friday the 13th

âParamount released a mock-slasher flick,

Student Bodies,

which parodied the genre just as the

Scream

series would do fifteen years later. In one scene, the obligatory nubile teenage babysitter hears a noise outside a suburban house; she opens the door to investigate, finds nothing, and then goes back inside. As the door shuts behind her, the camera swoops in on the doorknob, and we see that she's left the door unlocked. The camera pulls back, and then swoops down again, for emphasis. And then a flashing arrow appears on the screen, with text that helpfully explains: “Door Unlocked!”

That flashing arrow is parody, of course, but it's merely an exaggerated version of a device popular stories use all the time. It's a kind of narrative signpost, planted conveniently to help the audience keep track of what's going on. When the villain first appears in a movie emerging from the shadows with ominous, atonal music playingâthat's a flashing arrow that says: “bad guy.” When a sci-fi script inserts a non-scientist into some advanced lab who keeps asking the science geeks to explain what they're doing with that particle acceleratorâthat's a flashing arrow that gives the audience precisely the information they need to know in order to make sense of the ensuing plot. (“Whatever you do, don't spill water on it, or you'll set off a massive explosion!”) Genre conventions function as flashing arrows; the

Student Bodies

parody works because the “door unlocked” text is absurd overkillâwe've already internalized the rules of the slasher genre enough to know that nubile-babysitter-in-suburban-house inevitably leads to unwanted visitors. Heist movies traditionally deliver a full walk-through of the future crime scene, complete with architectural diagrams, so you'll know what's happening when the criminals actually go in for the goods.

These hints serve as a kind of narrative handholding. Implicitly, they say to the audience, “We realize you have no idea what a particle accelerator is, but here's the deal: all you need to know is that it's a big fancy thing that explodes when wet.” They focus the mind on relevant details: “Don't worry about whether the babysitter is going to break up with her boyfriend. Worry about that guy lurking in the bushes.” They reduce the amount of analytic work you need to make sense of a story. All you have to do is follow the arrows.

By this standard, popular television has never been harder to follow. If narrative threads have experienced a population explosion over the past twenty years, flashing arrows have grown correspondingly scarce. Watching our pinnacle of early eighties TV drama,

Hill Street Blues,

there's an informational

wholeness

to each scene that differs markedly from what you see on shows like

The West Wing

or

The Sopranos

or

Alias

or

ER. Hill Street

gives you multiple stories to follow, as we've seen, but each event in those stories has a clarity to it that is often lacking in the later shows.

This is a subtle distinction, but an important one, a facet of the storyteller's art that we sometimes only soak up unconsciously.

Hill Street

has ambiguities about future events: Will the convicted serial killer be executed? Will Furillo marry Joyce Davenport? Will Renko catch the health inspector who has been taking bribes? But the present tense of each scene explains itself to the viewer with little ambiguity. You may not know the coming fate of the health inspector, but you know why Renko is dressing up as a busboy in the current scene, or why he's eavesdropping on a kitchen conversation in the next. There's an open question or a mystery driving each of these storiesâhow will it all turn out?âbut there's no mystery about the immediate activity on the screen.

A contemporary drama like

The West Wing,

on the other hand, constantly embeds mysteries into the present-tense events: you see characters performing actions or discussing events about which crucial information has been deliberately withheld. Appropriately enough, the extended opening sequence of the

West Wing

pilot revolved around precisely this technique: you're introduced to all the major characters (Toby, Josh, CJ) away from the office, as they each receive the enigmatic message that “POTUS has fallen from a bicycle.”

West Wing

creator Aaron Sorkinâwho amazingly managed to write every single episode through season fourâdeliberately withholds the information that all these people work at the White House, and that POTUS stands for “President of the United States,” until the very last second before the opening credits run. Granted, a viewer tuning in to a show called

The West Wing

probably suspected that there was going to be some kind of White House connection, and a few political aficionados might have already been familiar with the acronym POTUS. But that opening sequence established a structure that Sorkin used in every subsequent episode, usually decorated with deliberately opaque information. The open question posed by these sequences is not: How will this turn out in the end? The question is: What's happening right now?

In practice, the viewers of shows like

Hill Street Blues

in the eighties no doubt had moments of confusion where the sheer number of simultaneous plots created present-tense mystery: we'd forget why Renko was wearing that busboy outfit because we'd forgotten about the earlier sequence introducing the undercover plot. But in that case, the missing information got lost somewhere between our perceptual systems and our short-term data storage. The show gave us a clear vista on to the narrative events; if that view fogged over, we had only our memory to blame. Sorkin's shows, on the other hand, are the narrative equivalent of fog machines. You're

supposed

to be in the dark. Anyone who has watched more than a handful of

West Wing

episodes closely will know the feeling: scene after scene refers to some clearly crucial piece of informationâthe cast members will ask each other if they saw “the interview” last night, or they'll make enigmatic allusions to the McCarver caseâand after the sixth reference, you'll find yourself wishing you could rewind the tape to figure out what they're talking about, assuming you've missed something. And then you realize that you're supposed to be confused.

The clarity of

Hill Street

comes from the show's subtle integration of flashing arrows, while

West Wing

's murkiness comes from Sorkin's cunning refusal to supply them. The roll call sequence that began every

Hill Street

episode is most famous for the catchphrase “Hey, let's be careful out there.” But that opening address from Sergeant Esterhaus (and in later seasons, Sergeant Jablonski) performed a crucial function, introducing some of the primary threads and providing helpful contextual explanations for them. Critics at the time remarked on the disorienting, documentary-style handheld camerawork used in the opening sequence, but the roll call was ultimately a comforting device for the show, training wheels for the new complexity of multithreading.

Viewers of

The West Wing

or

Lost

or

The Sopranos

no longer require those training wheels, because twenty-five years of increasingly complex television has honed their analytic skills. Like those video games that force you to learn the rules while playing, part of the pleasure in these modern television narratives comes from the cognitive labor you're forced to do filling in the details. If the writers suddenly dropped a hoard of flashing arrows onto the set, the show would seem plodding and simplistic. The extra information would take the fun out of watching.

This deliberate lack of handholding extends down to the micro level of dialogue as well. Popular entertainment that addresses technical issuesâwhether they are the intricacies of passing legislation, or performing a heart bypass, or operating a particle acceleratorâconventionally switches between two modes of information in dialogue: texture and substance. Texture is all the arcane verbiage provided to convince the viewer that they're watching Actual Doctors At Work; substance is the material planted amid the background texture that the viewer needs to make sense of the plot.

Ironically, the role of texture is sometimes to be directly

irrelevant

to the concerns of the underlying narrative, the more irrelevant the better. Roland Barthes wrote a short essay in the sixties that discussed a literary device he called the “reality effect,” citing a description of a barometer from Flaubert's short story “A Simple Heart.” In Barthes's description, reality effects are designed to create the aura of real life through their sheer meaninglessness: the barometer doesn't play a role in the narrative, and it doesn't symbolize anything. It's just there for background texture, to create the illusion of a world cluttered with objects that have no narrative or symbolic meaning. The technical banter that proliferates on shows like

The West Wing

or

ER

has a comparable function; you don't need to know what it means when the surgeons start shouting about OPCAB and saphenous veins as they perform a bypass on

ER

; the arcana is there to create the illusion that you are watching real doctors. For these shows to be enjoyable, viewers have to be comfortable knowing that this is information they're not supposed to understand.