Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (10 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

5.

Have you an approach to the patient which is sympathetic and practical? This means knowing at least enough about a patient’s non-medical circumstances to understand what might affect his or her ability to have treatment and how different treatments might affect the patient; for example, financially because of a particular occupation.

6.

Have you recognised the problem the patient thinks is most important?

These simple principles are worth keeping in mind as you interview and examine your long-case patient. They should help you work out what the examiners will consider important and what sorts of questions they are likely to ask.

CHAPTER 5

The cardiovascular long case

A rule of thumb in the matter of medical advice is to take everything any doctor says with a grain of aspirin.

Goodman Ace (1899–1982)

Ischaemic heart disease

Patients with recent acute coronary syndromes, including myocardial infarction, are always available for long cases if required. Many patients with more exotic medical problems will also have ischaemic heart disease. The whims of the long-case examiners may lead to concentrated questioning about the ischaemic heart disease of a patient in hospital for the management of, say, renal transplant rejection. These patients are more likely to present management rather than diagnostic problems once they reach the status of long-case patients.

There have been important changes in the classification of patients with episodes of acute coronary ischaemia. These are based on electrocardiogram (ECG) changes and on the detection of markers of myocardial damage (troponins), which have prognostic as well as diagnostic usefulness for patients with chest pain. Patients with chest pain and raised troponin levels have had a myocardial infarction, even if the creatine kinase level is not elevated. Those who present with chest pain and ECG changes of ST elevation have an ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Those without ST elevation are said to have a non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS), but once abnormal cardiac markers have been detected the diagnosis can be revised to a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI). The diagnosis

unstable angina

is no longer part of this classification, but is still often used to describe patients with increasing exertional angina.

Patients with ST elevation benefit from urgent action to re-open the blocked coronary artery (angioplasty or thrombolytic treatment). Those with non-STEMI are usually treated medically in the first instance. The presence of abnormal cardiac markers indicates an adverse prognosis (increased risk of further infarction or death) and these patients benefit from early but not immediate intervention (angioplasty or coronary surgery) and from immediate aggressive anti-platelet treatment and anticoagulation with fractionated or

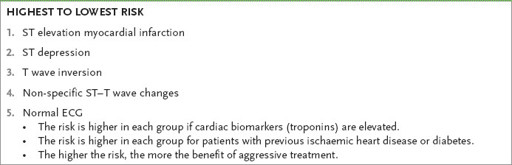

unfractionated heparin. Non-STEMI patients who have ST depression on the ECG have a worse prognosis than those with T wave inversion or flattening. The concept of risk stratification is based on these factors and determines the urgency and type of treatment.

The history

1.

Find out whether the patient has been or is in hospital because of a recent myocardial infarction or an acute coronary syndrome or for some other cardiac or non-cardiac reason. The patients with the worst prognosis are those with chest pain and ECG changes at rest (see

Table 5.1

). Clearly, these may represent different pathophysiological states, varying from occlusion of a coronary artery and inadequate collateral flow to rupture of a lipid-rich plaque with thrombus formation. Ask about obvious precipitating factors, such as a gastrointestinal bleed or the onset of an arrhythmia. Questions need to be asked about the character of the chest pain and what precipitated the admission.

Table 5.1

Risk stratification in patients with ischaemic chest pain at rest

Remember that the diagnosis of angina can be suspected from the history, but needs to be established by investigations – an abnormal ECG or exercise test at least. You should be suspicious of the diagnosis unless it has been confirmed by investigations. The most common differential diagnosis is gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). This can be difficult to prove without endoscopy (and, if normal, oesophageal pH testing), but an excellent response to a trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is very suggestive. Oesophageal spasm is another cause of central chest pain.

2.

Detail the patient’s current treatment. Oral medications will probably include:

•

aspirin with or without an ADP inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel)

•

a beta-blocker or occasionally a calcium antagonist

•

nitrates (intravenous, oral or topical)

•

statin

•

an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor (AR) blocker (ARB).

MANAGEMENT HISTORY

1.

Acute coronary syndromes are managed with heparin and aspirin and clopidogrel or prasugrel. Remember that prasugrel should not be used in patients older than 75.

Thrombolytic treatment is not effective for NSTEACS. This is possibly because acute coronary syndromes are not a single pathological entity and also because a state of increased thrombogenesis may follow initial thrombolysis with these drugs.

Most patients have early angiography (within 48 hours) with the intention of angioplasty to the culprit lesion if this is practical. Ask whether the patient knows details of what investigations or treatment were performed.

2.

If the patient has had an infarct during this or previous admissions find out about the management, which may have included primary angioplasty or thrombolysis, and treatment of complications such as arrhythmias, cardiac failure, further angina and embolic events.

3.

In many hospitals a comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation program will have been offered to the patient. Ask whether this has been helpful and ask about the hospital staff’s explanations to the patient about his or her condition and prognosis. Also ask questions about the effect of this illness on the patient’s life and work.

4.

Next ask standard questions about risk factors in addition to age and male sex. Remember that risk factors are of vital importance to long-term prognosis, but add little to the likelihood that undiagnosed chest pain is ischaemic. Risk factors include:

•

previous ischaemic heart disease

•

hyperlipidaemia

•

diabetes mellitus (the increased risk in these patients is as high as that in non-diabetics who have already had an ischaemic event)

•

hypertension

•

family history (in particular, first-degree relatives with ischaemic heart disease before the age of 60; 92-year-old great-uncles with heart trouble do not count)

•

smoking

•

use of oral contraceptives or premature onset of menopause

•

obesity and physical inactivity

•

high serum homocysteine levels, which may have been measured if the patient has premature coronary disease and few other risk factors – levels in the top population quintile increase coronary risk twofold; trials of treatment (mostly with folate), however, have been negative and routine treatment is not recommended

•

long-term use, in high doses, of cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (which should be stopped)

•

erectile dysfunction (which often precedes symptomatic ischaemic heart disease and is a marker of endothelial dysfunction). Remember that the presence of multiple risk factors is more than additive.

5.

Then find out whether risk factor control has been successful. Remember the important results of recent secondary prevention trials.

a.

Aggressive cholesterol lowering to below a level of 4 mmol/L of total cholesterol (LDL <1.8) is now considered appropriate for patients with established coronary disease.

b.

There is some evidence that statins have beneficial effects beyond their effect on cholesterol levels (pleotrophic effects).

6.

Find out what investigations the patient can remember.

a.

An echocardiogram may have been performed to assess ventricular function and possible complications of infarction, such as a pericardial collection, a left ventricular thrombus, mitral regurgitation or a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

b.

An exercise test, a sestamibi or a stress echocardiogram may have been performed to assess ischaemia or myocardial viability (MRI scan).

c.

Cardiac catheterisation is perhaps the most memorable of the investigations for ischaemic heart disease.

The patient may know how many coronaries are abnormal and whether angioplasty was performed. Ask whether a drug-eluting stent (DES) was used and for how long dual anti-platelet treatment was recommended. Remember clopidogrel, and most PPIs, use the same metabolic pathway in the liver and if used together may result in a theoretical loss of anti-platelet benefit. The clinical relevance of this is disputed.

7.

Complications such as acute mitral regurgitation or an infarct-related VSD are usually treated surgically but have a relatively poor prognosis. All complications are less common if early coronary patency and normal flow have been achieved.

The examination

Examine the cardiovascular system (Ch 16).

1.

Note the presence of intravenous treatment. This might include heparin, nitrates, inotropes, vasopressors or antiarrhythmic drugs.

2.

Record the blood pressure.

3.

Look for signs of valvular heart disease, cardiac failure, rhythm disturbances (e.g. atrial fibrillation, frequent ectopic beats) and murmurs suggesting mitral regurgitation or a VSD caused by an infarct.

4.

There may be spectacular bruises at venepuncture or femoral puncture sites if the patient has had thrombolytic treatment. Abdominal wall bruising suggests subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin therapy, and a bruise (sometimes very large) over one of the femoral arteries suggests cardiac catheterisation or angioplasty. If radial angiography was performed there may be a bruise over the radial artery at the wrist. Occasionally the radial pulse may be absent. More general complications include a stroke owing to embolism from the heart.

Management

It is best to concentrate on discussing the management of the presenting problem. If the patient has only recently been admitted with an infarct, this means a discussion of thrombolysis and primary angioplasty.

1.

Candidates should have some knowledge of the major thrombolysis and angioplasty trials.

a.

These have shown that early treatment has improved mortality. Treatment up to 12 hours after the onset of an infarct is worthwhile.

b.

The indications and contraindications to the use of these techniques need to be well understood. The major differences between streptokinase and the fibrin-specific drugs (tPA (alteplase) or reteplase) are important. Streptokinase is much cheaper. Alteplase and reteplase have been shown to produce a small survival advantage, probably because they are more effective in opening occluded vessels, but have a slightly increased risk of causing cerebral haemorrhage. Alteplase is the drug of choice for patients who have had a previous dose of streptokinase more than a few days before. This is because antibodies to streptokinase develop within a few days and may cause an allergic reaction to a second dose, thus reducing its effectiveness.

c.

Alteplase is given as a bolus followed by an infusion, and reteplase is given as a double bolus injection with a 30-minute interval. Even when thrombolysis seems successful (resolution of symptoms and ST depression) patients are now routinely transferred so that angiography can be performed as soon as practical.

2.

Urgent coronary (primary) angioplasty, if available, is of proven benefit and has been shown to reduce mortality compared with treatment with thrombolytic drugs.

a.

The advantages, theoretical and real, include definite re-opening of the infarct-related artery in more than 90% of patients (compared with <60% of patients given thrombolytics), normal flow in the infarct-related artery in most cases, dilatation and stenting of the offending (culprit) lesion and often removal of clot, very low risk of stroke and shortening of hospital stay, often to only 3 days.

b.

Patients are treated with potent anti-platelet drugs: aspirin, clopidogrel (or prasugrel or ticagrelor) and sometimes with one of the platelet aggregation inhibitors, abciximab or tirofiban. Prasugrel is more rapidly effective than clopidogrel and in

many protocols is now preferred for primary angioplasty patients. Ticagrelor may improve prognosis compared with the other drugs. Its most common side-effect is dyspnoea, which may develop after 5–10 days.