Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (30 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

The Romans were the first to draw glass into sheets for windows, around 400

B.C

., but their mild Mediterranean climate made glass windows merely a curiosity. Glass was put to more practical purposes, primarily in jewelry making.

Following the invention of glass blowing, around 50

B.C

., higher-quality glass windows were possible. But the Romans used blown glass to fashion drinking cups, in all shapes and sizes, for homes and public assembly halls. Many vessels have been unearthed in excavations of ancient Roman towns.

The Romans never did perfect sheet glass. They simply didn’t need it. The breakthrough occurred farther north, in the cooler Germanic climates, at the beginning of the Middle Ages. In

A.D

. 600, the European center of window manufacturing lay along the Rhine River. Great skill and a long apprenticeship were required to work with glass, and those prerequisites are reflected in the name that arose for a glassmaker: “gaffer,” meaning “learned grandfather.” So prized were his exquisite artifacts that the opening in the gaffer’s furnace through which he blew glass on a long rod was named a “glory hole.”

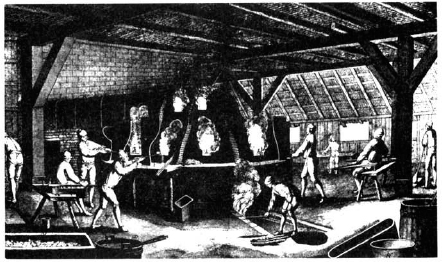

Glassmakers employed two methods to produce windows. In the cylinder method, inferior but more widely used, the glassmaker blew molten silica into a sphere, which was then swung to and fro to elongate it into a cylinder. The cylinder was then cut lengthwise and flattened into a sheet.

In the crown method, a specialty of Normandy glassmakers, the craftsman also blew a sphere, but attached a “punty” or solid iron rod to it before cracking off the blowing iron, leaving a hole at one end. The sphere would then be rapidly rotated, and under centrifugal force the hole would expand until the sphere had opened into a disk. Crown glass was thinner than cylinder glass, and it made only very small window panes.

During the Middle Ages, Europe’s great cathedrals, with their towering stained-glass windows, monopolized most of the sheet glass manufactured on the Continent. From churches, window glass gradually spread into the houses of the wealthy, and still later, into general use. The largest sheet, or plate, of cylinder glass that could be made then was about four feet across, limiting the size of single-plate windows. Improvements in glass-making technology in the seventeenth century yielded glass measuring up to thirteen by seven feet.

Gaffers producing glass windows by two ancient methods

.

In 1687, French gaffer Bernard Perrot of Orleans patented a method for rolling plate glass. Hot, molten glass was cast on a large iron table and spread out with a heavy metal roller. This method produced the first large sheets of relatively undistorted glass, fit for use as full-length mirrors.

Fiberglass

.

As its name implies, fiberglass consists of finespun filaments of glass made into a yarn that is then woven into a rigid sheet, or some more pliant textile.

Parisian craftsman Dubus-Bonnel was granted a patent for spinning and weaving glass in 1836, and his process was complex and uncomfortable to execute. It involved working in a hot, humid room, so the slender glass threads would not lose their malleability. And the weaving was performed with painstaking care on a jacquard-type fabric loom. So many contemporaries doubted that glass could be woven like cloth that when Dubus-Bonnel submitted his patent application, he included a small square sample of fiberglass.

Safety Glass

.

Ironically, the discovery of safety glass was the result of a

glass-shattering accident in 1903 by a French chemist, Edouard Benedictus.

One day in his laboratory, Benedictus climbed a ladder to fetch reagents from a shelf and inadvertently knocked a glass flask to the floor. He heard the glass shatter, but when he glanced down, to his astonishment the broken pieces of the flask still hung together, more or less in their original contour.

On questioning an assistant, Benedictus learned that the flask had recently held a solution of cellulose nitrate, a liquid plastic, which had evaporated, apparently depositing a thin coating of plastic on the flask’s interior. Because the flask appeared cleaned, the assistant, in haste, had not washed it but returned it directly to the shelf.

As one accident had led Benedictus to the discovery, a series of other accidents directed him toward its application.

In 1903, automobile driving was a new and often dangerous hobby among Parisians. The very week of Benedictus’s laboratory discovery, a Paris newspaper ran a feature article on the recent rash of automobile accidents. When Benedictus read that most of the drivers seriously injured had been cut by shattered glass windshields, he knew that his unique glass could save lives.

As he recorded in his diary: “Suddenly there appeared before my eyes an image of the broken flask. I leapt up, dashed to my laboratory, and concentrated on the practical possibilities of my idea.” For twenty-four hours straight, he experimented with coating glass with liquid plastic, then shattering it. “By the following evening,” he wrote, “I had produced my first piece of Triplex [safety glass]—full of promise for the future.”

Unfortunately, auto makers, struggling to keep down the price of their new luxury products, were uninterested in the costly safety glass for windshields. The prevalent attitude was that driving safety was largely in the hands of the driver, not the manufacturer. Safety measures were incorporated into automobile design to prevent an accident but not to minimize injury if an accident occurred.

It was not until the outbreak of World War I that safety glass found its first practical, wide-scale application: as the lenses for gas masks. Manufacturers found it relatively easy and inexpensive to fashion small ovals of laminated safety glass, and the lenses provided military personnel with a kind of protection that was desperately needed but had been impossible until that time. After automobile executives examined the proven performance of the new glass under the extreme conditions of battle, safety glass’s major application became car windshields.

“Window

.”

There is a poetic image to be found in the origin of the word “window.” It derives from two Scandinavian terms,

vindr

and

auga

, meaning “wind’s eye.” Early Norse carpenters built houses as simply as possible. Since doors had to be closed throughout the long winters, ventilation for smoke and stale air was provided by a hole, or “eye,” in the roof. Because the wind frequently whistled through it, the air hole was called the “wind’s

eye.” British builders borrowed the Norse term and modified it to “window.” And in time, the aperture that was designed to let in air was glassed up to keep it out.

Home Air-Cooling System: 3000

B.C

., Egypt

Although the ancient Egyptians had no means of artificial refrigeration, they were able to produce ice by means of a natural phenomenon that occurs in dry, temperate climates.

Around sundown, Egyptian women placed water in shallow clay trays on a bed of straw. Rapid evaporation from the water surface and from the damp sides of the tray combined with the nocturnal drop in temperature to freeze the water—even though the temperature of the environment never fell near the freezing point. Sometimes only a thin film of ice formed on the surface of the water, but under more favorable conditions of dryness and night cooling, the water froze into a solid slab of ice.

The salient feature of the phenomenon lay in the air’s low humidity, permitting evaporation, or sweating, which leads to cooling. This principle was appreciated by many early civilizations, which attempted to cool their homes and palaces by conditioning the air. In 2000

B.C

., for instance, a wealthy Babylonian merchant created his own (and the world’s first) home air-conditioning system. At sundown, servants sprayed water on the exposed walls and floor of his room, so that the resultant evaporation, combined with nocturnal cooling, generated relief from the heat.

Cooling by evaporation was also used extensively in ancient India. Each night, the man of the family hung wet grass mats over openings on the windward side of the home. The mats were kept wet throughout the night, either by hand or by means of a perforated trough above the windows, from which water trickled. As the gentle warm wind struck the cooler wet grass, it produced evaporation and cooled temperatures inside—by as much as thirty degrees.

Two thousand years later, after the telephone and the electric light had become realities, a simple, effective means of keeping cool on a muggy summer’s day still remained beyond the grasp of technology. As late as the end of the last century, large restaurants and other public places could only embed air pipes in a mixture of ice and salt and circulate the cooled air by means of fans. Using this cumbersome type of system, the Madison Square Theater in New York City consumed four tons of ice a night.

The problem bedeviling nineteenth-century engineers was not only how to lower air temperature but how to remove humidity from warm air—a problem appreciated by ancient peoples.

Air-Conditioning

. The term “air-conditioning” came into use years before anyone produced a practical air-conditioning system. The expression is credited to physicist Stuart W. Cramer, who in 1907 presented a paper on

humidity control in textile mills before the American Cotton Manufacturers Association. Control of moisture content in textiles by the addition of measured quantities of steam into the atmosphere was then known as “conditioning the air.” Cramer, flipping the gerundial phrase into a compound noun, created a new expression, which became popular within the textile industry. Thus, when an ambitious American inventor named Willis Carrier produced his first commercial air conditioners around 1914, a name was awaiting them.

An upstate New York farm boy who won an engineering scholarship to Cornell University, Carrier became fascinated with heating and ventilation systems. A year after his 1901 graduation, he tackled his first commercial air-cooling assignment, for a Brooklyn lithographer and printer. Printers had always been plagued by fluctuations in ambient temperature and humidity. Paper expanded or contracted; ink flowed or dried up; colors could vary from one printing to the next.

A gifted inventor, Carrier modified a conventional steam heater to accept cold water and fan-circulate cooled air. The true genius of his breakthrough lay in the fact that he carefully calculated, and balanced, air temperature and airflow so that the system not only cooled air but also removed its humidity—further accelerating cooling. Achieving this combined effect earned him the title “father of modem air-conditioning.” With the groundwork laid, progress was rapid.

In 1919, the first air-conditioned movie house opened in Chicago. The same year, New York’s Abraham and Straus became the first air-conditioned department store. Carrier entered a profitable new market in 1925 when he installed a 133-ton air-conditioning unit at New York’s Rivoli Theater. Air-conditioning proved to be such a crowd pleaser in summer that by 1930 more than three hundred theaters across America were advertising cool air in larger type than their feature films. And on sweltering days, people flocked to movies as much to be cooled as to be entertained. By the end of the decade, stores and office buildings were claiming that air-conditioning increased workers’ productivity to the extent that it offset the cost of the systems. Part of that increase resulted from a new incentive for going to work; secretaries, technicians, salesclerks, and executives voluntarily arrived early and left late, for home air-conditioning would not become a widespread phenomenon for many years.

Lawn: Pre-400

B.C

., Greece

Grass is by far humankind’s most important plant. It constitutes one quarter of the earth’s vegetation and exists in more than seven thousand species, including sugarcane, bamboo, rice, millet, sorghum, corn, wheat, barley, oats, and rye. However, in modern times, “grass” has become synonymous with “lawn,” and a form of the ancient once-wild plant has evolved into a suburban symbol of pride and status.