Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (25 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

In the chronological (and rapid) order of their debuts, giving early applications, the miracle plastics were:

• Cellophane, 1912—a transparent food wrap

• Acetate, 1927—soap dishes, bathroom tumblers

• Vinyl, 1928—tablecloths, garment bags, shower curtains

• Plexiglas, 1930—wall partitions, windows, boats

• Acrylics, 1936—novelty items, sweaters

• Melmac, 1937—dinnerware

• Styrene, 1938—drinking glasses, refrigerator egg trays

• Formica, 1938—kitchen countertop laminate; developed as a substitute

for mica

, a naturally occurring, heat-resistant mineral

• Polyester, 1940—clothing

• Nylon, 1940—toothbrush handles and bristles (see page 209), stockings (see page 346)

Tupperware: 1948, United States

To assume that Tupperware, developed by Massachusetts inventor Earl S. Tupper, is nothing more than another type of plastic container is to underestimate both the Dionysian fervor of a Tupperware party and the versatility of polyethylene, a synthetic polymer that appeared in 1942. Soft, pliant, and extremely durable, it ranks as one of the most important of household plastics.

Among polyethylene’s earliest molders was Du Pont chemist Earl Tupper, who since the 1930s had had the dream of shaping plastics into everything from one-pint leftover bowls to twenty-gallon trash barrels. Tupper immediately grasped the important and lucrative future of polyethylene.

In 1945, he produced his first polyethylene item, a seven-ounce bathroom tumbler. Its seamless beauty, low cost, and seeming indestructibility impressed department store buyers. A year later, a trade advertisement announced “one of the most sensational products in modern plastics,” featuring Tupper’s tumblers “in frosted pastel shades of lime, crystal, raspberry, lemon, plum and orange, also ruby and amber.”

Next Tupper developed polyethylene bowls, in a variety of sizes and with a revolutionary new seal: slight flexing of the bowl’s snug-fitting lid caused internal air to be expelled, creating a vacuum, while external air pressure reinforced the seal.

Plastic kitchen bowls previously were rigid; Tupper’s were remarkably pliant. And attractive. The October 1947 issue of

House Beautiful

devoted

a feature story to them: “Fine Art for 39 cents.”

As good a businessman as he was a molder, Earl Tupper took advantage of the windfall national publicity afforded Tupperware. He devised a plan to market the containers through in-home sales parties. By 1951, the operation had become a multimillion-dollar business. Tupperware Home Parties Inc. was formed and retail store sales discontinued. Within three years, there were nine thousand dealers staging parties in the homes of women who agreed to act as hostesses in exchange for a gift. The firm’s 1954 sales topped $25 million.

Satisfied with the giant industry he had created, Earl Tupper sold his business to Rexall Drugs in 1958 for an estimated nine million dollars and faded from public view. Eventually, he became a citizen of Costa Rica, where he died in 1983.

In and Around the House

Central Heating: 1st Century, Rome

There was a time when the hearth and not the cathode-ray tube was the heart of every home. And though it would seem that electronic cathode-ray devices like television, video games, and home computers most distinguish a modern home from one centuries ago, they do not make the quintessential difference.

What does are two features so basic, essential, and commonplace that we take them for granted—until deprived of them by a blackout or a downed boiler. They are of course lighting and central heating. A crisis with these, and all of a home’s convenience gadgets offer little convenience.

Roman engineers at the beginning of the Christian era developed the first central heating system, the hypocaust. The Stoic philosopher and statesman Seneca wrote that several patrician homes had “tubes embedded in the walls for directing and spreading, equally throughout the house, a soft and regular heat.” The tubes were of terra cotta and carried the hot exhaust from a basement wood or coal fire. Archaeological remains of hypocaust systems have been discovered throughout parts of Europe where Roman culture once flourished.

The comfort of radiative heating was available only to the nobility, and with the fall of the Roman Empire the hypocaust disappeared for centuries. During the Dark Ages, people kept warm by the crude methods primitive man used: gathering round a fire, and wrapping themselves in heavy cloaks of hide or cloth.

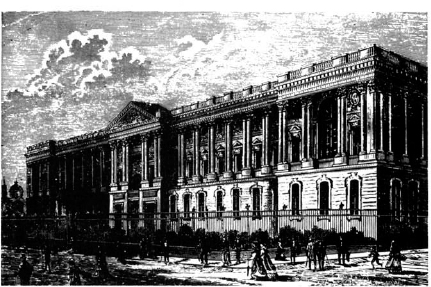

Louvre, Paris. Before its conversion into an art museum, the royal palace on the Seine boasted one of the first modern hot-air systems for central heating

.

In the eleventh century, huge centrally located fireplaces became popular in the vast and drafty rooms of castles. But since their construction allowed about eighty percent of the heat to escape up the chimney, people still had to huddle close to the fire. Some fireplaces had a large wall of clay and brick several feet behind the flames. It absorbed heat, then reradiated it when the hearth fire began to die down. This sensible idea, however, was used only infrequently until the eighteenth century.

A more modern device was employed to heat the Louvre in Paris more than a century before the elegant royal palace on the Seine was converted into an art museum. In 1642, French engineers installed in one room of the Louvre a heating system that sucked room-temperature air through passages around a fire, then discharged the heated air back into the room. The air, continually reused, eventually became stale. A hundred years would pass before inventors began devising ways to draw in fresh outdoor air to be heated.

The first major revolution in home heating to affect large numbers of people arrived with the industrial revolution in eighteenth-century Europe.

Steam energy and steam heat transformed society. Within a hundred years of James Watt’s pioneering experiments with steam engines, steam, conveyed in pipes, heated schools, churches, law courts, assembly halls, horticultural greenhouses, and the homes of the wealthy. The scalding surfaces of exposed steam pipes severely parched the air, giving it a continual

odor of charred dust, but this trifling con was amply outweighed by the comforting pro, warmth.

In America at this time, many homes had a heating system similar to the Roman hypocaust. A large coal furnace in the basement sent heated air through a network of pipes with vents in major rooms. Around 1880, the system began to be converted to accommodate steam heat. In effect, the coal furnace was used to heat a water tank, and the pipes that had previously carried hot air now transported steam and hot water to vents that connected to radiators.

Electric Heater

. In the decade following home use of Edison’s incandescent lamp came the first electric room heater, patented in 1892 by British inventors R. E. Crompton and J. H. Dowsing. They attached several turns of a high-resistance wire around a flat rectangular plate of cast iron. The glowing white-orange wire was set at the center of a metallic reflector that concentrated heat into a beam.

The principle behind the device was simple, but the success of the electric heater rested completely on homes’ being wired for electricity, an occurrence prompted almost entirely by Edison’s invention. Improved models of the prototype electric heater followed rapidly. Two of note were the 1906 heater of Illinois inventor Albert Marsh, whose nickel-and-chrome radiating element could achieve white-hot temperatures without melting; and the 1912 British heater that replaced the heavy cast-iron plate around which the heating wire was wrapped with lightweight fireproof clay, resulting in the first really efficient portable electric heater.

Indoor Lighting: 50,000 Years Ago, Africa and Europe

“The night cometh, when no man can work.” That biblical phrase conveyed earlier peoples’ attitude toward the hours of darkness. And not until late in the eighteenth century would there be any real innovation in home lighting. But there were simply too many hours of darkness for man to sleep or remain idle, so he began to conceive of ways to light his home artificially.

First was the oil lamp.

Cro-Magnon man, some fifty thousand years ago, discovered that a fibrous wick fed by animal fat kept burning. His stone lamps were triangular, with the wick lying in a saucerlike depression that also held the rank-smelling animal fat. The basic principle was set for millennia.

Around 1300

B.C

., Egyptians were lighting their homes and temples with oil lamps. Now the base was of sculpted earthenware, often decorated; the wick was made from papyrus; and the flammable material was the less malodorous vegetable oil. The later Greeks and Romans favored lamps of bronze with wicks of oakum or linen.

Until odorless, relatively clean-burning mineral oil (and kerosene) became

widely available in the nineteenth century, people burned whatever was cheap and plentiful. Animal fat stunk; fish oil yielded a brighter flame, but not with olfactory impunity. All oils—animal and vegetable—were edible, and in times of severe food shortage, they went into not the family lamp but the cooking pot.

Oil lamps presented another problem: Wicks were not yet self-consuming, and had to be lifted regularly with a forceps, their charred head trimmed off. From Roman times until the seventeenth century, oil lamps often had a forceps and a scissors attached by cord or chain.

To enable him to work throughout the night, Leonardo da Vinci invented what can best be described as history’s first high-intensity lamp. A glass cylinder containing olive oil and a hemp wick was immersed in a large glass globe filled with water, which significantly magnified the flame.

There was, of course, one attractive alternative to the oil lamp: the candle.

Candle: Pre-1st Century, Rome

Candles, being entirely self-consuming, obliterated their own history. Their origins are based, of necessity, on what early people wrote about them.

It appears that the candle was a comparative latecomer to home illumination. The earliest description of candles appears in Roman writings of the first century

A.D

.; and Romans regarded their new invention as an inferior substitute for oil lamps—which then were elaborately decorative works of art. Made of tallow, the nearly colorless, tasteless solid extract from animal or vegetable fat, candles were also edible, and there are numerous accounts of starving soldiers unhesitantly consuming their candle rations. Centuries later, British lighthouse keepers, isolated for months at a time, made eating candles almost an accepted professional practice.

Even the most expensive British tallow candles required regular half-hour “snuffing,” the delicate snipping off of the charred end of the wick without extinguishing the flame. Not only did an unsnuffed candle provide a fraction of its potential illumination, but the low-burning flame rapidly melted the remaining tallow. In fact, in a candle left untended, only 5 percent of the tallow was actually burned; the rest ran off as waste. Without proper snuffing, eight tallow candles, weighing a pound, were consumed in less than a half hour. A castle, burning hundreds of tallow candles weekly, maintained a staff of “snuff servants.”

Snuffing required great dexterity and judgment. Scottish lawyer and writer James Boswell, the biographer of Samuel Johnson, had many occasions to snuff tallow candles, not all successfully. He wrote in 1793: “I determined to sit up all night, which I accordingly did and wrote a great deal. About two o’clock in the morning I inadvertently snuffed out my candle…and could not get it re-lumed.”

Reluming a candle, when the household fire had been extinguished, could be a time-consuming chore, since friction matches had yet to be invented.

Cervantes, in

Don Quixote

, comments on the frustrations of reluming a candle from scraps of a fire’s embers. Snuffing tallow candles so often extinguished them, it is not surprising that the word “snuff” came to mean “extinguish.”

Up until the seventeenth century, part of a theatrical troupe consisted of a “snuff boy.” Skilled in his art, he could walk onto a stage during a scene’s emotional climax to clip the charred tops from smoking candles. While his entrance might go ignored, his accomplishment, if uniformly successful, could receive a round of applause.

The art of snuffing died out with the widespread use of semi-evaporating beeswax candles late in the seventeenth century. Beeswax was three times the price of tallow, and the wax candles burned with a brighter flame. British diarist Samuel Pepys wrote in 1667 that with the use of wax candles at London’s Drury Lane Theater, the stage was “now a thousand times better and more glorious.”

The Roman Catholic Church had already adopted the luxury of beeswax candles, and the very rich employed them for special occasions that called for extravagance. Household records of one of the great homes of Britain show that during the winter of 1765, the inhabitants consumed more than a hundred pounds of wax candles a month.