Extraordinary Theory of Objects (2 page)

Read Extraordinary Theory of Objects Online

Authors: Stephanie LaCava

When I was eleven, I decided to buy land in Brazil. It cost around fifty dollars, brokered through a mail-order conservation society. Two weeks after sending in payment, a sheet of paper arrived entitling me to an acre of rain forest. I thought that if I ever needed to run away, the plot would be there, undeveloped, with hundredsâthousandsâof

poison arrow tree frogs

*

surfing in wait for me. In the meantime, I had created the Amazon in my bedroom. Little figurines of the neon creatures were arranged throughout my bookshelves, while my walls were painted jungle green bordered with my best attempt at illustrated macaw parrots. My mother had let me decorate however I liked. I spent hours setting up my plastic frogs, finding the perfect spot for my favorite blue-and-yellow-speckled one. My love for him led me to lie on my bed, with its banana leaf sheets, and daydream of where I'd find his family and other crazy beasts. I didn't know then that I would soon have to leave this safe, make-believe rain forest.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

I learned of the upcoming change in the parking lot of a strip mall just outside of Boston. We were in Massachusetts for Thanksgiving with my grandmother, at the grocery store for some milk and life-changing news.

“You've always wanted to go to Paris,” my father said, staring at me from the driver's seat of the car. I knew his face as a composition of two brown dots and a neat half-moon of facial hair that moved whenever he spoke. Sometimes I would watch his

mustache

*

instead of looking at his eyes. He was always calm, measured, and unflappable, like a spy from the movies. Based on his demeanor, elusive work, and routine travels, I believed he was a real-life secret government agent. My father was rarely in the States for longer than three weeks, and I spent so many hours imagining him that he'd become something of a myth.

“We're moving to France,” he said.

I laughed. He did not.

“Seriously, Stephie.”

“Why?” I asked.

“My job. I have an assignment overseas.”

“Can't you just travel like you already do? Make a lot of conference calls? You could use that computer mail Prodigy-thing you just installed?” Before we left for the holiday, my father had shown me some strange device called a modem, which he plugged into the computer to send written notes over phone lines.

He shook his head. There was nothing for me to read. He rarely showed physical evidence of emotion. I was the opposite. The tears came immediately.

“IâI'm not sure I want to leave my friends.”

“You never stop talking about travel; and you tell us how you don't really get along with the girls here, except for Ashley and Claire.”

I bit my bottom lip and shook my head. He was correct. “Yes, but this is different.”

“Not so much. It's a great opportunity for you and your brother.”

“How?”

“Stephie, you will get to live in another country and understand it in a real way.”

“What does that even mean?”

“Trust me, it's different from taking a trip. You know little of what else is out there.” The mustache did not move. I had no choice but to trust him.

He didn't know that for all that opportunity there would be just as much pain.

I clutched my backpack to my chest as we cleared security at the airport. My long, unruly red hair kept getting tangled in the straps. My mother was occupied watching my brother as he tried to run ahead to the gate. She didn't ask why I chose to hold the bag so closely. The man at security didn't either. He waved me past. No one looked inside to see what I was carrying with me. Buried beneath two stuffed frogs, an

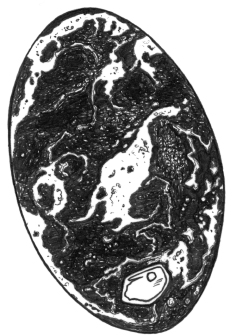

ancient Egyptian sarcophagus

*

â

shaped metal pencil case, and a Discman was a large,

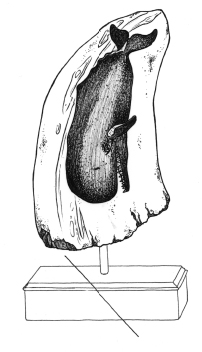

curved whale's tooth

.

*

My father had given the ivory piece to me some time ago, knowing I would keep it safe in my collection. I was told I had started stockpiling pretty things when I was three, beginning with a foil-covered egg I didn't realize was chocolate until a friend took a bite. The whale tooth was a souvenir from one of my father's Nantucket holidays as a child. I loved it. Not only did it belong to him, to his mustache and gentle heart, but the tooth also symbolized fantasy. To me, it could have been the horn of a narwhal, or part of a Minotaur, though neither was as exotic as my father. I could read about these creatures, whereas there was no guidebook for my parents. Before my father left to go ahead of my mother, brother, and me to France, we had all sat together at the kitchen table to discuss our strange future.

“Where are we going to live?” I had asked.

“We found a house.” The mustache did not move.

“A house? Don't people live in apartments in Paris?”

“We're going to be just outside the city, in a town called Le Vésinet.” It suddenly made sense why my father and my mother had gone overseas a month ago and left us to stay at my friend Claire's house. “Zach will have a backyard to play in, and you will love the park there, Les Ibis. It is filled with swans and there is a special pink palace, the Palais Rose.” I couldn't listen. I was angry with him for not asking us, for not even telling us, until the arrangements were all settled.

“Why didn't you tell me?”

“It didn't make sense to share the news until it was all set. You will go to a small international school in Neuilly-sur-Seine.”

I felt as though I was being briefed like one of his colleagues, which made me feel grown-up.

“We will leave the third week in April. You will start school the day after your birthday. You will fly with your mother and brother, as I will already be in France, working and making sure everything is ready. The movers will come and pack what we won't need right away to be shipped in a container at sea and arrive in a few months. Put aside what you'll need sooner. We are keeping our house here, so you can leave certain things behind.”

I didn't answer. Anything I would have said would be cut with sarcasm, which my father would not appreciate.

Again came the tears.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

The whale's tooth lay hidden in my backpack as we boarded the plane.

“Stephie, are you ready?” my mother asked. She tried to take my hand. I pulled away. The move could not have been an easy decision for her; she would play single parent much of the time in a foreign place. Yet I blamed her, because it was easyâshe was emotional, but not fragile. I was both.

“I'm fine.”

I held the tooth beneath a blanket the entire flight.

Upon arrival in France, I unpacked my little sack on the wooden floor of my new, empty bedroom. There was a large arched window on the left wall covered in rusty white-metal shutters that I couldn't figure out how to open. I stayed in the dark, exhausted to the point where I could barely sit up. One, two, three, there they were: my whale tooth, my poison arrow frog, and the sarcophagus pencil case. I lined the objects up around me on the floor where there was a little light coming through the slits of the shutters, so each one sat on a sunbeam. I spoke to the frog, “Welcome to France, I know it's not quite the rain forest.” He didn't say anything in return.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

I woke up later that night with my head nestled on my backpack. It was completely dark and very cold. A blanket was at my feet. My mother must have come in while I was sleeping. I had no idea what time it was or if anyone else was awake. There was a little light in the hall outside the door. I stood up and lifted the blanket, wrapping it around my shoulders. It was quiet; everyone was sleeping. I walked softly through the hall and down the stairs. There was another light coming from outside. I went across the kitchen and unlatched the back doors. A half-moon was in the sky over a broken-down little house that must have belonged to the gardener. I decided to have a look, trampling a few yellow tulips before finding myself at a rotting gray door. It opened easily, letting some little creature out with a gust of stale air. Inside, the floor was covered in shards of terra-cotta pots and remains of a stained glass window. I kicked something that made a sharp clang as it hit the wall. It was a

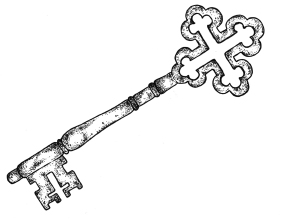

skeleton key

.

*

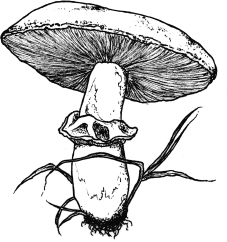

I bent down to pluck a

mushroom

*

from the wet ground. Clusters of them had sprung up along the path to the park. I sank deep into the mud, my new sneakers covered in thick brown paste. My mother had finally allowed me to buy a pair of skateboarding shoes like the other kids at school. Kneeling, I tried to keep my feet in the air as I pulled at the plant with its red cap and cream-colored spots. I braced my legs against a tree, lifting my thin slip dress to let my knees touch the earth. It was difficult to see. The sun wouldn't rise for another two hours.

I liked to walk alone in the dark. The first time I had tried a late-evening stroll was two days after our arrival in France, the night of the skeleton key. Sneaking out at night became my escape from days filled with books and silence, a boredom verging on insanity, locked inside with my little belongings and endless ruminations. My brother too had become uncharacteristically quiet and withdrawn since the move, shutting himself in his room, leaving only for a croissant from the kitchen before returning to his toy cars. He had always shown signs of being odd, evidence that I wasn't a changeling after all, but his behavior, like mine, grew stranger by the day. He, my mother, and I moved through the house, airy versions of our old selves, coasting over the cold marble floors. My mother's Oriental rugs wouldn't arrive for another month, the same for her toile de Jouy curtains, and the same for her husband. He'd been traveling for much of the year. The entire house was hollow and icy, even though it was only early September. It was warmer outside.

I had taken a pale tan

cardigan

*

with me when I left the house in case the wind stirred up as the sun started to rise over the streets. The left shoulder of the sweater slipped off, exposing the thin strap of my dress, as I yanked at the mushroom. The root gave way, and I fell backward. The slip flew up, and my bare bottom hit the ground. My back and legs, like my sneakers, were now covered in dirt. I stood, shook the dress down, and pulled the cardigan on, all with my left hand, as my right held tightly to the mushroom. The freshly picked plant wouldn't last forever, but long enough to sit on a shelf and lend its charm to my new collection.

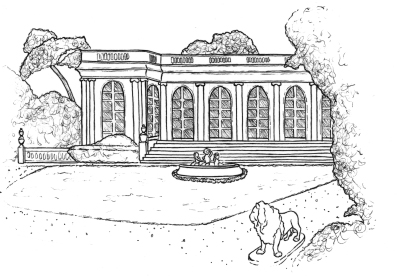

There were more patches of mushrooms huddled together at the corner of the street leading to the park. The mottled markings on my skin matched the patterns on their hats. I knew the park Les Ibis wasn't far from rue Ampère, where we lived, but I wasn't sure exactly how to get there, and I couldn't ask anyone. The few women I walked by looked at me with disdain, because of my sneakers. They were dressed in long skirts or tiny fitted suits with heels. I didn't care, feeling rather invisible anyway. I was the French cartoon character Fantômette. By following a young woman pushing an old-fashioned stroller, I found the entrance. We took two rights and a left, past a roundabout and the green painted gate. Two swans stalked nearby with beady eyes and orange beaks. One ducked its head into the neck of the other. This one then flicked her wings and spread her orange web toes as she waddled back into the water to float among branches and fallen leaves. Her friend followed, and they both coasted toward the Palais Rose across the pond. The mansion looked like a film set, with its pink-and-white pillar marble façade and massive black-and-gold gate. I read its history off of the plaque on the ground. In 1900, Arthur Schweitzer had commissioned the mansion to be built after the Grand Trianon at Versailles. It was then sold to Ratanji Jamsetji Tata for three pearls and an emerald. The next owner was Comte Robert de Montesquiou, Proust's “Professor of Beauty.” There, in Le Vésinet, Montesquiou entertained the likes of Sarah Bernhardt and Auguste Rodin. In 1922, the

Marchesa Luisa Casati

*

came to live at the Palais Rose with her library of books on the occult, pavilion of portraits, mechanical panther, stuffed boa constrictor, Blue Rolls-Royce, and wax effigies.

That morning, as my sneakers grew soggy in the manicured grounds, I stood in front of the grand house, trying to imagine its old owner, the insane and beautiful Marchesa Casati. I thought I saw someone in the window with almond eyes, holding a candle, though the image was only one of many daydreams. They happened often, because I was so unbalanced: on the best days, I experienced a realism deficiency with an excess of whimsy. Some people's bodies need to make extra blood cells or insulin for survival; mine manufactured fantasy. This marble palace at the end of my park was comfort against the creeping tediousness of my days and odd new faithless impulses. I had to try to sort through what exactly I was doing in this foreign place. The swans honked, and I stepped backward.

Without quotidian American distractions, I became aware of my thoughts as I never had before. My growing insecurity wasn't rooted in anything specific that happened, but rather what didn't happen. It was on walks like this that I began to notice how my head dealt with the world. I wasn't wired for contentment. All these fears, all these thoughts, they wouldn't stop, unless I buried them with stories and random information. Numbers suddenly became important to me. I liked to do everything in even counts. Some superstitious reasoning told me that odd meant something bad would soon happen.

Not once that morning had I considered the feelings of my mother back at the house, perhaps terrified, looking for me in an empty bedroom as the sun rose. I knew it was insensitive, but I couldn't bring myself to go home. Instead I walked around Les Ibis exactly four times and then toward town.

There were two shopping areas in Le Vésinet. The larger one was just beyond the silver stag roundabout with streets of gourmet shops, a general store, and an ice-skating rink near the site of the outdoor market. I walked toward the older, smaller center with its boulangerie, épicerie, North African traiteur, and papeterie. It had been over three hours since I'd left the house and I was feeling unusually hungry. I had a ten-franc bill rolled up in my shoe.

The man who ran the épicerie was a small, tan Algerian who spoke in patient unintelligible words. I liked him from my first visit to his shop, with my mother, to find some milk. He had offered me an electric-colored candy from the plastic bins he kept stacked by the cash register. I had chosen a red ribbon covered in little sour crystals. He recognized me immediately. I was thankful he was open so early.

“Qu'est ce que tu veux?”

he asked, looking at me with gentle eyes.

I lifted my shoulders knowing very little French yet.

“Des bonbons?”

He pointed to the stacked clear containers.

I nodded, not caring that this would be my breakfast. Those sorts of societal conventions had never meant much to me: mealtimes, talking in turn. He passed his hand over the bins of green frogs with crème bellies, sunny-side eggs with yellow centers, and rainbow sour strips. I shook my head. He lifted his finger.

From beneath the counter he pulled out a lovely little oval box printed with two lovers amid tiny purple flowers. I nodded. He pried it open, and inside were sugar-dusted

violet candies

.

*

I'd never eaten anything flower flavored before, but I picked one up and placed it on my tongue. It was wet, natural, and sweet, like I imagined the earth would have tasted had I taken a handful from the lawn in front of the Palais Rose and shoveled it into my mouth.

I left the little man with a small bag of the violet candies. He had refused my ten francs and insisted on giving me the sweets. I'd never been in a shop alone with its owner, nor one where we couldn't communicate, but we shared something of a bond. After all, he wasn't from France either. I paused for a moment in front of his green-and-yellow-striped awning with a white-spotted red mushroom in one hand and a bag of purple candies in the other. The sun had come up, lighting this part of Le Vésinet to resemble a scenic throwback to seventies small-town America. A Deux Chevaux crackled by a roundabout planted with primary-colored tulips and lilies of the valley, which would arrive from beneath the ground in the spring. I wasn't sure I knew how to get back to rue Ampère, to my house, and to my mother and brother inside. But I started home, eyes fixed on the street.

Then, I saw it: a violent blue spark in the sidewalk, which quickly paled to discrete white, like a shy phantom. It sparked again, this time, illuminating purple and pink. I bent over, holding the mushroom in one hand while letting the candy fall to the puddle-covered ground. My knees, caked with dirt, began to drip mud. I pulled my cardigan up over my shoulders as I picked up the glittering object. With my free hand I lifted the thing as if it were the tail of a snake covered in creamy blue and lavender spots. I was holding an antique

opal necklace

,

*

somehow lost and forgotten. It may have been exhaustion, or simply my anemic common sense, but it didn't strike me as that strange a discovery or that it belonged to someone else. I picked up the candies and continued walking back to the house with my mushroom, violets, and fiery jewelry.