Extraordinary Theory of Objects (3 page)

Read Extraordinary Theory of Objects Online

Authors: Stephanie LaCava

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A few days later my father was finally back. The last time he'd been in France was prior to the first shipment of furniture and before setting off to North Africa, or somewhere like that. He was at my bedroom door.

“Come in, Dad.” As I sat up he ran over to me and gave me a hug.

“I missed you.”

“Then why did you go for so long?” I asked. He said nothing and the mustache didn't move.

“What's this I hear about you bringing fungus inside?” My mother had been begging me to throw away the plant I had put on the shelf as part of my collection.

“It's my mushroom.”

“And you need it here on your windowsill, why?”

“Look at how beautiful it is!”

“That is one nice mushroom,” he said.

“Please, Dad, don't be like Mom, she's annoying enough.”

“How about I make a deal with you?”

“What?”

“You lose the mushroom, and I take you somewhere special today filled with things just like itâbetter things, things you can't even imagine.”

“I don't believe you.”

“Have I ever lied to you?” It was true; every crazy thing he'd ever said had come true.

“Fine, take my mushroom.” I sighed as I watched him walk over to the windowsill, crawling with little black bugs.

“You still have the tooth I gave you! The one from Nantucket.”

“Yes, I like it.”

“I loved that tooth when I was little. I took it with me everywhere. What's that key for?” he asked.

“I don't know.”

“We will have to find out. For now, get dressed, we are going on a little trip.”

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

It took us an hour and a half with traffic to drive from Le Vésinet to our destination in Paris. My father planned to park in a garage, which meant our car had to be inspected first by police. Everyone was on high alert because of the recent bombings by Algerian insurgents. My father showed the men his papers, and they seemed satisfied after a quick sweep of the backseat and trunk. When they were done, we drove down one level and found an empty spot. Neither of us said a word as we got out of the car and locked the doors. I quietly followed my father into the elevator to the ground floor. When we stepped onto the street he motioned me to the left, and we walked two blocks before reaching the entrance to the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, the museum of natural history.

“We're here,” my father said as we took our place at the end of the ticket line behind a tall teenage boy and his girlfriend. I suddenly felt self-conscious, having barely brushed my hair. I was wearing a blue-and-white long-sleeve sailor stripe sweater underneath a yellow T-shirt, and loose, faded black leggings with my skateboarding sneakers. My hair was matted and tumbling down my shoulders in gnarled red strands. I watched as the boy took the girl's hand after they paid and led her into the museum.

“Stephie?” my father said.

“Yeah?”

“Where are you? Let's go.” He put his hand on my shoulder and steered me to the main hall.

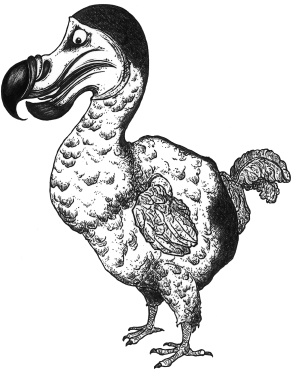

There, at the heart of the museum, was a taxidermy parade: a timeline of stuffed animals from prehistoric reptiles to present day. An enormous scaled lizard led creatures like a fat woolly mammoth, Indian elephant, Bengal tiger, and big-horned ram. I loved their beady eyes and frozen bodies and that unlike their dynamic former selves, they could go nowhere. They were enduring objects rather than beasts. “You see that?” my father said, pointing ahead. “That's a real

dodo bird.

*

They're extinct now. You can't find one anywhere.” But there one was, with its squat, feathered body and curved beak.

“How many are there in the world?” I asked, immediately enchanted.

“I think this is the only one left.”

“No?”

“Yes, unless you count those that survive in stories.”

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

We'd been in France for over six months, well, more like four, considering we'd spent the summer back in New York. Instead of growing familiar, my surroundings became filled with more curious customs, places, and people, but I no longer felt the excitement of initial discovery. Les Ibis, the Palais Rose, Paris even, I went to all of them each week, and while they still managed to mesmerize a little, they weren't enough to keep me from falling into a kind of numbness. Somehow cynicism had crept over my fantastical thinking. I was mostly alone that year. I rode the bus to school and listened to my Discman while the girl in the back row threw gum wrappers at my head. The girls at school didn't like me very much. They had never given me a chance, decided immediately that I didn't belong, which was funny, as they didn't eitherâat least not in France. They made me feel as if I had done something wrong, and they spoke badly about me to each other. Through my own odd rationalization, I decided excommunicating me meant they belonged to something, simply because I did not. They didn't like that I had a growing friendship with the boys, either, although the one I wanted most was taken. I had met all twenty of the other people in my grade, and none of them seemed quite right for me. If I did the math, one over twenty was the fractional equivalent in the world of negative-something-crazy over all the people out there, which meant there wasn't much chance at a real friend. Despite being so young, that's how I thought, in fatal absolutes and always in numbers.

Come the new academic year, the old class would be replaced with another set of students who had just moved overseas. Only a few remained year after yearâand still the same insensitivity.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

My family celebrated Halloween that October, as Americans tend to do. My brother and I hung white ghosts in the trees of the backyard and carved pumpkins. Our neighbor proceeded to complain to the town about the pagans living next door. As pagans, we also celebrated Thanksgiving together, while none of Europe did at all.

Much of the American population would take off to Euro Disney for the expatriate version of the holiday feast. My brother, mother, and I followed them. My father was away. There, we ran around and rode the rides before congregating for a faux turkey dinner at the Buffalo Bill's theme restaurant. The only problem was that I couldn't relax and enjoy the insanity of the whole scene: five hundred misplaced Americans in a cartoon fantasyland. I became obsessed with checking every gift shop, looking for the Alice in Wonderland section and maybe a stuffed dodo bird.

I hadn't left my bedroom in two days. My mother had tried to get me to come out for meals, but I'd refused. It was my plea to be recognized as prisoner-in-residence. I didn't eat all that much anymore. My face was permanently gaunt and red, a shade lighter than my hair, from hours of crying, and my body was pale and weak from the ongoing hunger strike. It didn't matter that my mother, my father, and my brother all loved me. I only felt dramatic rejection of everything. As a family we'd taken trips I should have been thankful for; to the rocky beaches in Marbella, the tiny town of Bruges, and then the last winter, skiing in Courchevel. Yet, on every holiday, I spent my time looking around for something else, waiting for someone to notice me, trying to engage with strangers, hoping to feel some kind of excitement. Inspired by Cécile in

Françoise Sagan

's

*

Bonjour

Tristesse

, I sought an understanding of grown-up affairsâand attention from grown-up men. Cécile had admitted that she was “more gifted in kissing a young man in the warm sunshine than in taking a degree.” It worried me that I was the opposite; I'd never kissed a boy, but school had never been a problem. I was dedicated to my studies; they distracted me from the other part of my mind. When Cécile mentioned she was trying to write an essay about Pascal, I immediately knew all about him. Adult attention, though, was only another daydream, as no one cared for a skinny little elf girl. I didn't want to swim or ski, I only wanted to know what it would be like to sit and laugh among friends or with a lover. The part of my mind that was supposed to rationalize a pragmatic approach to problems was led by an automatic calibration of negativity. It was a chemical sadness, a slowly growing depression.

There was a knock and then shuffling footsteps. Someone had pushed something under the door. I stood up from my bed. I'd been wearing the same pale nude slip dress for the past three days. After listening to make sure no one was in the hall, I slid the door open and found a tiny bouquet of

lilies of the valley

*

with a note on the floor. I had forgotten it was May 1, the day when the French celebrate hope and spring and give the tiny flowers to loved ones. I opened the piece of my mother's cream-colored stationery. “I grew these for you, Love, Mom.” It was true. She had planted them when we arrived. So much time had gone by since then, nearly two years, and now they were here and I wasn't any longer.

I knew it was incredibly thoughtful. The little blossoms looked perfect on my vanity's glass shelf next to the whale's tooth and tiny frog figurine. My collection had grown too large for the windowsill. I sat on the carved wooden stool in front of the round mirror and combed my tangled hair. I was newly aware of a tingling in my stomach and thighs that made me crazy to find someone, to think about sexual affairs, a fantasy love life. I wanted to be a player in the adult world. I imagined that a special man would give me the hope and confidence I lacked on my own. Yet instead of leaving my room to find him, or even make a friend, I shut myself inside. I preferred to sit on my bed Indian style and reread my worn copy of D'Aulaires'

Book of Greek Myths

. I liked to learn the details of each deity and try to pair him or her with someone I knew. It was a way of organizing everyone, fitting them into a system. The Greek gods were like people, but more beautiful and could do nothing terribly wrong.

I imagined I would like to be Iris. She seemed so lovely and carefree, wearing a dress of iridescent water droplets, making her way along the rainbow. And if I were a greater goddess, perhaps I would be Aphrodite emerging from a shell, my naked body covered in

pearls

.

*

My match was more Persephone, though, kidnapped into the underworld. Even her name sounded like mine.

At the top of Olympus was a girl in my grade named Charlotte. She had been at our school the longest, since kindergarten. Brought up in Switzerland, she spoke perfect French and was very pretty, with a small nose and ample chest. Her father was a powerful banker, her mother somehow connected to royalty. They lived in a two-floor town house, and her bedroom was still decorated with Ludwig Bemelmans's characters from

Madeline

. She always had crumpets from Marks & Spencer, the English store with shops throughout Paris. Her sister had already graduated and gone on to Lawrenceville in New Jersey for high school. When her sister visited she always wore punk-grunge clothing, like shirts from the brand Fuct or Stussy, or one of those orange-lined green bomber jackets from an army-navy store. I believed Charlotte led the other girls against me. She'd been there forever. It was easy to trust her word.

Then there was Natalie. Perhaps less interesting than Charlotte, though more beautiful, she was an army brat from California who had moved around her whole life. She was known for French-kissing under tables in the cafeteria and twirling her hair. She was the real Aphrodite. I admired her sexy, brazen ways. She sometimes talked back to Charlotte and always to our teachers.

Sarah's father was the CEO of some company that made things no one understood. She had moved to France from Connecticut, not far from the town where I had lived back in the States. Her thin blond hair was always pulled back in one of those silver clips you'd find at an American drugstore in the nineties. Sarah was Athena, smart and sturdy.

As for the boys, there were three who were particularly intriguing, and sometimes kept company with the above. Jake had moved to France from Tokyo and his father ran an American bank. He loved Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Quentin Tarantino, and Pamela Anderson. Navy blue sweat suits were his uniform of choice. He and I had similar spirits, and it may have been this bond that made me a little uncomfortable with him. Instead of embracing his quirkiness, I was sometimes repelled by it, because it mirrored so much of my own. Jake was American and best friends with Raees, who was half South African, half American. The two of them were inseparable, always making movies together with Jake's camcorder. I had fallen in a teenage love-obsession with Raees. Whereas Jake was just like me, Raees wasn't at all. He seemed stoic and confident and didn't really know that I existed, unlike Jake, who, in his own weird way, seemed to care about me. Raees's mother was a purported spy, newly married to a Swedish prince. Maybe she knew my father. Here were Apollo and Aries.

Michael, I knew only for a little while, as he decamped with his family to Rome soon after my arrival at school. He played Zeus, at least from what I had heard, for the duration of his rule.

Other classmates included Aashif, whose father was the ambassador from Kuwait, and Akiyo from Japan with his rocket-scientist mother. He was close with Seiya, who was also Japanese, and best friends with Palat, a Thai prince. They always seemed to have the latest gadgets and technology. They were the Three (Eurasian) Fates.

In the older crowd, there was a brooding boy named Tim, who was Hades. Then there was Sophie, who was Helen of Troy, beautiful and cool. She was dating a boy who was a skaterârough and rather grown-up and the brother of her best friend.

Among the younger children were Titans like Melanie, the daughter of the founder of the most fashion-forward store in Paris, and Henrik, the son of a famous tennis player and a model. He would grow up to be a professional basketball player, celebrated in his own right.

After some consideration, I decided that if I could choose, I would want to be Artemis, a waiflike virgin hunting goddess, rather than Iris. The mythology game worked well as a method of classification and exposition on character. That is, until everything went upside down. Problems started in our teenage lives because there wasn't the security of a Poseidon character to summon

rain

,

*

wipe out tragedy, and pacify uprisings and betrayals. We realized authority governed only in theory and as a construct of its own creation. We became aware that teachers and parents couldn't control what we thought they could when one of our classmates died of cancer and someone's father committed suicide. Around the same time, one of our teachers explained that when Kurt Cobain sang “Rape Me,” he meant it metaphorically, which became useful in social studies as a way to understand Rudyard Kipling's feelings about imperialism. I learned to play basketball in an empty pool at the American Church. Instead of crossing guards, men with machine guns sometimes stood watch at the school gate.

At least once a month, there was a bomb threat and we had to evacuate a few times. The news often reported the Algerians clashing with the French. Every time there was a Métro bombing, I worried that my father had been among the casualties. It mattered little that he was usually not in Paris at the time; I always assumed the worst.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

It was the sound of rain starting to fall slowly outside my window that made me finally leave my room come nighttime. I stood up, unhinged, and pushed open the rusted shutters to look into the garden. It was the perfect weather for a walk. I padded quietly down the marble stairs, through the kitchen, to the back door, which opened quietly. I was barefoot and the stones on the landing felt cold beneath me. I walked slowly with my head lifted to the sky, catching the raindrops in my hair. The shower was still soft enough that I could sit in the garden without shelter. There was a circular cement pedestal littered with birdseed offerings nearby the shed. I pulled myself up onto it. Again, I lifted my head to the sky. Something started to crawl over my foot. I looked down, and there was a

beetle

,

*

its shell burnt red with black markings. I tried to pick it up, but it opened its wings and flew away. Then I noticed all the other beetles. They were everywhereâshiny chartreuse shells, big black monsters, ladybirds, and tiny brown ones. I watched them tour the slab I had sat down on before escaping into the backyard at large. One went straight for the lilies of the valley. The rain began to fall harder around me. I had once read that beetles were the most diverse and populous species. I was comforted knowing there was nowhere I could go where I wouldn't be able to find some kind of beetle to keep me company.