Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (13 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

Here is Jane in American Constitutional Law…

This two-course sequence, which she took during the fall and spring semesters of her first year, was taught Tuesday and Thursday mornings by a regular law school professor,

Neil T. Dowling, a tall, dignified, fifty-three-year-old Alabamian with a bent for the Socratic method. It was said of him when he retired many years later that he had a gift for conveying “the inherent grandeur of the human effort represented by the Constitution”; that his aim always was “to create a feeling of involvement in an exhilarating inquiry.”

With Jane Butzner, it seems, he succeeded.

Jane was no lawyer and never aimed to become one. The course used Dowling’s own thick text,

Cases on Constitutional Law

, which featured debates bearing on the regulatory powers of government going back to before the Constitution. What motivated her to take it, and why she was permitted to—it was normally an elective reserved for second-year law students—is murky; by any standard, she was unqualified for it.

But at some point, probably as part of a class project, Jane found herself rooting through old articles, editorials, and speeches citing ideas voiced at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Soon she was poring through notes of the Convention proceedings themselves, as recorded by James Madison and others during those momentous days. And these, in turn, exposed her to a whole panoply of suggestions that had

not

made their way into the Constitution—that were rejected, seen as foolish or wrongheaded, or in the end simply voted down.

For example, the Constitution says legislative power is vested in a Senate and a House of Representatives. But Jane learned that William Paterson of New Jersey thought

a single house would be quite enough and that Benjamin Franklin thought so, too. Of course, Rufus King of Massachusetts thought there ought to be

three

houses—“

the second to check the first and to be proportionate to the population, the third to represent the states and have equal suffrage.” The Constitution says Congress can overturn a presidential veto with a two-thirds vote. But someone back in 1787 argued that three-quarters would be better, more stabilizing, that “the

danger to the public interest from the instability of laws is most to be guarded against.”

Here is where Jane’s story takes an improbable turn: somehow, in all those failed suggestions, those ideas that went nowhere, those thoughtful, or not so thoughtful, challenges to all we today take as Constitutional Truth, Jane Butzner found the material for her first book. Jane was a first-year college student, barely out of high school. She was new to constitutional law. Yet two decades before

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

made her famous, Columbia University Press in 1941 issued, under Jane’s own name,

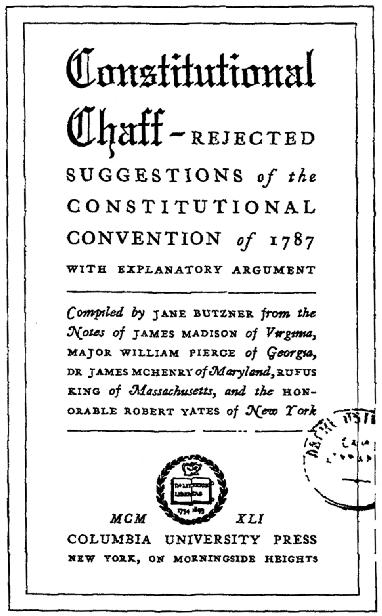

Constitutional Chaff—Rejected Suggestions of the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

It is easy to see in the very idea of the book hints of her contrariness, of a deep-lying anti-authoritarian sensibility; she herself seems to have been alive to it. “It seems like

a faithless thing,” she wrote in the introduction, “to

emphasize the differences of opinion, the plans which met disfavor.” But no, she made it clear, those errant, futile, or misguided arguments needed no apology. Some of them were quite ingenious. More striking to her yet was the grit and determination with which, through them, their proponents sought a common goal—“a government calculated for man’s, every man’s happiness.” Far from diminishing the achievement of the men of Philadelphia, she was saying, those “rejected suggestions” honored the American experiment.

Appearing twenty years before

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

was Jane’s first book

, Constitutional Chaff.

In her preface, Jane expressed hope that her book might invite speculation on how a different Constitution could have led to a different America—if, to use her example, it had decreed that the Senate remain always in session, and that it, rather than the president, preside over foreign affairs. Her book, then, was in the spirit of what today is called “counterfactual history,” the serious scholarly consideration of what might have unfolded had events turned out otherwise—if, say, Lee had won at Gettysburg.

She hoped her book would be enjoyed, she said, “by those who read for the

best possible reason—entertainment.” And there

was

a species of entertainment in

Constitutional Chaff

—in the brash conceit of its central idea; in the sheer perversity of some of the suggestions Jane dignified by her attention to them; in how the Framers cut and parried their way to the One True Constitution. And, of course, in her attached Appendix C—the delegate William Pierce’s sometimes wicked

Character Sketches

of his Convention colleagues: “With an

affected air of wisdom,” said Pierce of Delaware’s John Dickinson, for example, “he labors to produce a trifle.”

Set against Jane’s future work,

Constitutional Chaff

might be reckoned slight; it was merely a “compilation,” Jane’s own voice seemingly silent. But not entirely; it

did

reflect her sensibilities. It was contrary. It was serious; a “compendium of ideas,” she called it. It expressly valued reading pleasure. By early spring of 1940 Jane had probably finished putting together the text and proposed it to Columbia University Press. By May the press’s associate director, Charles G. Proffitt, wrote to Professor Dowling, then on sabbatical at the University of Virginia, for his views. Dowling wrote back that it was “

a well done job by a very careful student” and that the manuscript would be useful to scholars. But not

many

scholars, he felt bound to admit—“a most limited market, if indeed it could be called a market at all.”

On July 15, Jane learned that her manuscript was approved for publication, but that “finances” posed a problem. Some $350 beyond the press’s own resources would be needed to go ahead with it. Did she know “

of any source from which we might draw this amount…?” If so, they’d be happy to place her under contract and schedule the book to appear the following year.

Three days later, Jane called Henry H. Wiggins, the Columbia Press officer who’d written her of this little wrinkle, peppering him with questions about how her book would be distributed, how much it would sell for, and the like. She admitted, as Higgins wrote in a memo, “that she would have

some difficulty in raising the money, but would think the matter over and let us know.”

Three hundred and fifty dollars was seven months’ rent for Jane and her sister; or, when she was working, three months’ pay. Think of it as at least $5,000 today. Where would she get such a sum? Could she?

Her father’s death had begotten a substantial

life insurance settlement,

which would support Mrs. Butzner for the rest of her life and had probably loosened things up financially for the family. Soon after his death, Jane had stopped working and enrolled at Columbia. The following January,

Mrs. Butzner sent her a check to help her visit Philadelphia; plainly, Jane had not cut the purse strings. Now, with opportunity beckoning, she doubtless turned to her family once more. She may also have turned to her first employer in New York, Robert Hemphill, who had become both her friend and, very much more, Betty’s, and was often to be seen around the Morton Street apartment until his death the following year at age sixty-four. In any event, on July 22 Jane wrote Wiggins that she could come up with the money.

The book appeared, in an edition of about eleven hundred copies, at $2.25 each, in January 1941, early copies reaching her in time to hand out to her family at Christmas. “

I am delighted with the appearance of the book,” Jane wrote Proffitt on January 2, “and am very much impressed with the care and taste which the Press has given it in every respect.” She liked the type used. She liked the binding. Even the book’s eight-page index “fills me with awe.”

The book was published by an important university press, the fourth-oldest in the United States and publisher of the works of two U.S. presidents. It found its way into libraries. It was reviewed here and there, cited in the literature. It bears reading even today—maybe especially today, when endless partisan infighting saps the nation’s strength and confidence. Jane writes of Hamilton, Franklin, and Edmund Randolph of Virginia, each with reservations about the Constitution, yet urging its ratification, or in other instances acting counter to their own convictions; the country’s good, in Jane’s words, “could best be obtained by

composing their own divergences, by compromising with one another.”

It is tempting, and true, to see this book, by an undereducated twenty-four-year-old, contributing to questions plumbed since the very birth of the republic, as early evidence of genius. We may see it equally, however, through the lens of Jane’s acknowledgment that her book “would not have been made without the encouragement and assistance of the members of my family.” From what we know of her growing-up years, this seems heartfelt and entirely genuine, and reaching far beyond that $350. In a copy of the book she gave her brother John, probably that Christmas, she thanked him for the book’s title and for his “

helpful counsel.” But the book’s dedication is neither to him, nor her mother, nor her

recently deceased father, but rather to something larger than any of them individually—“to 1712 Monroe Avenue,” her Scranton home, and all, and everyone, who had nurtured her there.

—

Just before registering for her first classes at Columbia in 1938, Jane took a

boat trip up the Atlantic coast to New England with Betty on something like a real vacation. Jane fell in love with Boston, at the time very much down on its economic luck. They visited Cape Cod, too, just missing the killer hurricane that swept through New England the following weekend.

In 1940, the two of them took a week-long bike trip in Quebec Province, where they visited, among other places, Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, a pilgrimage site whose Roman Catholic church had become a repository for crutches said to be discarded by the miraculously cured.

When, for six months each in 1939 and 1940, the New York World’s Fair took over Flushing Meadows Park, Jane visited its iconic Futurama Exhibition, boarding one of the little cars that introduced her and millions of others to General Motors’s modernist vision of fast and easy personal transportation, the superhighways of the future spread beneath them.

“I

thought it was so cute,” she’d tell an interviewer years later. “It was like watching an electric train display somewhere.”

“Did you have an inkling that this was going to turn out to be Dallas in 1985?”

“No,” she replied, “of course not.”

—

Also before starting at Columbia, Jane heard from her aunt Hannah, her grandmother’s seventy-seven-year-old sister, with a request she could not ignore.

After leaving Bloomsburg late in the last century, Hannah had gone on to study at the University of Chicago, teach Indians in the American West, then Aleuts and other natives for fourteen years in Alaska. Once back in Pennsylvania, where she regaled audiences with her adventures, she was won over to the idea of setting them down in print. Retrieving from her correspondents some of the letters she’d written from the wild, she put together a manuscript,

“A Woman Blazes a Trail in Alaska.”

Put together a manuscript?

“It would be more accurate, though uncharitable,” Jane would later write, “to say she

threw together a manuscript.” Aunt Hannah’s years in Alaska were no doubt trailblazing, but her account didn’t do them justice. “Reading it was a bit like contemplating a box of jigsaw-puzzle pieces,” Jane wrote. “The fragments were fascinating but maddeningly unassembled.” When Hannah first approached her, Jane said as much: the manuscript needed revision. At her age, though, Hannah was not about to tackle it herself. But

Jane

had written published magazine articles.

Jane

was a pro. Would

Jane

help her?

Jane tried. Hannah had had her manuscript typed up. Jane now worked up a new draft and, as she would write, sent it out over the next two years “to

some admirers who liked it, and to publishers who did not.” An awkward and belabored correspondence with a Philadelphia publisher, Dorrance, came to nothing. So did an approach to the University of Washington Press. So did all of Jane’s other efforts on Hannah’s behalf. “The book as a whole

moves along too slowly and does not make dramatic enough use of the incidents as they occur,” one publisher wrote back.

That was April 16, 1940. Aunt Hannah died a few days later. Jane put away the manuscript, not to take it up again for fifty years. “I

lacked sufficient craftsmanship” to make it into a good book, she’d write, “and knew it.”

—

By the spring of 1940, Jane had taken classes at Columbia for two years and was halfway toward a bachelor’s degree. She had sampled the sciences, and decided she “passionately

loved geology and zoology.” She’d taken four courses in economic geography, the field in which much of her later work could be said to belong. “For the first time I liked school and for the first time I made good marks,” mostly As.