Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (21 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

Later, she’d say that in a way she

hadn’t

been doing a good job at

Forum

—that as she’d listened to planners and architects, she’d too readily accepted what they had to say; did not question whether their lovely renderings and pretty models perhaps lacked something, or were misguided, or were just plain wrong. And that until she came to see it that way,

she

was wrong.

If we had to pin down a moment when that began to change, when Jane Jacobs began to see in a new way the streets and cities, buildings, plans, and architectural visions she had been writing about, it would probably be sometime in early 1955, in Philadelphia.

PART II

In the Big World

1954–1968

CHAPTER 9

DISENCHANTMENT

P

HILADELPHIA

, Jane wrote in a story about the city’s redevelopment in July 1955, was perhaps the only American city really grappling with the stark contrasts of urban life. She saw “an atmosphere of hope” there, in the initiative of private citizenry “thriving in the little and the large.” She marveled at the sheer scope of the city’s efforts, scattered over more than a dozen sites and ten thousand acres. She wrote of sunken gardens; of a food distribution center that would eliminate squatters’ shacks and burning dumps; of the architect Louis Kahn’s “clever and practical devices” for improving a poor district called Mill Creek. She lauded an “embrace of the new” that in Philadelphia “has by some miracle not meant the usual rejection of whatever is old.”

At intervals, Jane quoted the city’s planning commission director, the already legendary

Edmund Bacon, on his way to the cover of

Time

for his leadership of the city’s redevelopment programs. A native Philadelphian, forty-five, born of a staunchly conservative publishing family, Bacon was a graduate of Cornell’s school of architecture. He’d used an inheritance from his grandfather to travel the world, had wound up in Beijing, won a fellowship to study city planning at the University of Michigan, worked as a planner in Flint. By 1949, he was back in Philadelphia, pushing his ideas through the local bureaucracy, determined to clear away the debris of the city’s industrial past and create gleaming new modernist vistas; the city had not seen a major new office building go up in almost twenty years. Bacon, it could seem, was not just Philadelphia’s master planner, but America’s.

Not everyone liked him. “

Arrogant, arch, pompous, and wrong,” an architect who knew him later, Alan Littlewood of Toronto, would blithely call him. To Bacon’s enemies, an article in

Harper’s

would say, “he had risen too fast, succeeded too soon…‘Lord Bacon,’ they called him across the Schuylkill, at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts, disliking his arrogance, theatrical manner and impresario air.” Yet many appreciated that “he had accomplished more than any other town planner in the United States.” And, of course, it was Bacon—thin, ascetic looking, driven—who had helped fill Jane’s head with visions of Philadelphia’s future and supplied the sketches, plans, photos, and maps she’d expertly folded into a coherent narrative heralding a city on the move.

And yet it’s not clear how

much—or even, just possibly,

whether

—Jane visited Philadelphia to research her story. A certain remove from the city runs through her ten-page article, which is subtitled “A Progress Report” but reads more like a preview. Early on, she laments of American cities generally that the urban deserts within them “have grown and still they are growing, the

awful endless blocks, the endless miles of drabness and chaos.” Yet she is moved to the brink of poetry by the thought of all “the work that went into this mess,” the energy just below the surface, curdled into urban grit, which says “as much about the power and doggedness of life as the leaves of the forest in spring.” Later pages, stocked with illustrations of the new Independence Mall, Penn Center, and Mill Center, tell of “what is happening” in Philadelphia, or “will be happening,” or what “is going up,” of projects “under construction,” or “nearing completion.” But not much of the real, under-the-skin city emerges.

At some point, certainly, Jane did visit Philadelphia. There

she joined Bacon for a tour, letting him show off to her all he was proudest of. He was, of course, practiced at such showmanship, at one point treating Jane to a kind of before-and-after exercise in urban redevelopment. First they walked along a down-and-out street in a black neighborhood destined later for the Bacon treatment. It was crowded with people, people spilling out onto the sidewalk, sitting on stoops, running errands, leaning out of windows. Here was Before Street. Then it was off to After Street, the beneficiary of Bacon’s vision—bulldozed, the unsavory mess of the old city swept away, a fine project replacing it, all pretty and new.

Jane

, Bacon urged her,

stand right here, look down this street, look what we’ve done here.

She did. And certainly she could appreciate the vista Bacon offered her;

Yes, it’s very nice.

But there was something missing: people. Especially

so in contrast to that first street, which Jane recalled as lively and cheerful. Here, amid the new and rehabbed housing, what did she see? She saw one little boy—she’d remember him all her life—kicking a tire. Just him, alone on the deserted street.

Ed

, she said,

nobody’s here. Now, why is that? Where are the people? Why is no one here?

The way Jane told the story, Bacon didn’t offer a

Yes, but…

by way of explanation. He didn’t say,

Well, in a few years, as the neighborhood matures, we’ll see…

He offered no explanation at all. To Jane, he just wasn’t interested in her question, which irritated the hell out of her. She was puzzled, he wasn’t, and that was itself noteworthy. But more, for Jane the two streets seemed to point up some opposing lesson, or value, or idea, from that of Bacon—some sharply different sense of what mattered in a city and what did not, a divergent way of seeing. For Bacon, the new street exemplified all that was best in the new world that planners like him were making. For Jane, Bacon’s perspective was narrowly aesthetic, a question mostly of how it

looked;

to her, the new street represented not entirely a gain over the old, maybe no gain at all, but a loss, one that mocked Bacon’s plans and drawings and the glittering future they promised. “Not only did he and the people he directed not know how to make an interesting or a humane street,” she’d say, “but they didn’t even notice such things and didn’t care.” In time, scholars managed to find a measure of common ground between Bacon and Jacobs. But just now, they stood at the same spot, viewed the same streets, and saw them through different eyes.

Perhaps Bacon’s Philadelphia diverged too far from the one Jane had heard about from her parents, who’d met and courted there; or the Philadelphia she’d seen herself in the 1930s

visiting sister Betty at school; or on trips down from New York for

Iron Age

in the 1940s; or from some pure Platonic vision of City that had become part of her after twenty years in New York. Whatever the reason, the vehemence and frequency with which she’d later bring up the Bacon incident suggest no cool dissonance of values. Jane was angry—angry, it seems, at having been duped.

Jane’s recollections of her early years at

Forum

hint at a still youthful naïveté on which she’d look back ruefully. She’d visited Philadelphia, she’d say,

and found out what they had in mind and what they were planning to do and how it was going to look according to the drawings, what great things it was going to accomplish…I came back and wrote enthusiastic articles about this, and subsequently about other [cities], and all was well. I was in very cozy with the planners and project builders. I suppose my readers…well, I must ask them to forgive me now, whoever they were.

For what she saw now in Philadelphia was that the new projects didn’t look the way they were supposed to look and, more important, didn’t

work

the way they were supposed to work. Not if the boy kicking the tire down the street was any indication. Not if projects she’d heard glowingly described, or had even written about, were turning out as they did: “They weren’t delightful, they weren’t fine, and they were obviously never going to work right,” she wrote the Louisville writer Grady Clay in 1959. “Harrison Plaza and Mill Creek in Philadelphia were great shocks to me.”

“The artists’ drawings always

looked so seductive,” she’d all but shake her head in recalling. Yes, drawings specified the thickness of concrete walls and how air-handling systems were to be laid out. But they also

showed off.

They represented aesthetic vistas, how buildings, projects, and cities were to work. They showed people using them, trees and walkways, visions of the good life—often in bird’s-eye views that left the viewer with a sense of promise and parade at the urban prospect before her. And, of course, they were the work of architects and planners with a cultivated sense of design, drama, and spectacle. What Jane found in Philadelphia was that these visions didn’t match the city she met on the ground—not, at least, in ways that mattered to her.

The year or two before Jane’s Philadelphia article appeared may have been a bit stale for her at

Forum;

she’d written, for example, about how self-service displays were influencing store architecture. She tried doing a little freelancing on the side. She tried to interest

Reader’s Digest

in some

slices of Americana that had come down to her through the Butzner side of the family. She tried

science fiction, a retelling of the Adam and Eve story. She didn’t get very far.

But after Philadelphia, Jane returned to the

Forum

offices on fire, began talking of her disenchantment. Her disenchantment, you might ask, with just what? Actually, she may not have been able to put it very articulately or profoundly as yet. At

Forum

she had imbibed the architectural and planning truths of her day as much as anyone; whatever

bothered her was still new to her, something she probably didn’t entirely understand herself.

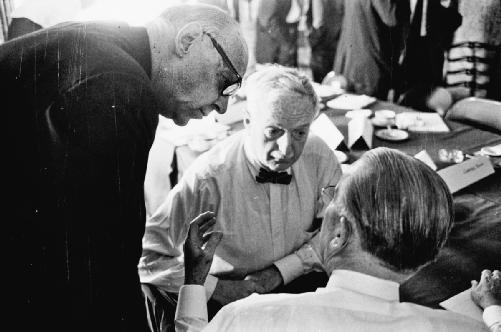

Doug Haskell, editor of

Architectural Forum,

during the time Jane worked there

Credit 10

In February 1955, about when Jane’s Philadelphia article was making its way through editors and graphic artists to publication, Doug Haskell wrote to his staff about how, “in view of

the terrific acceleration in the urban redevelopment picture,”

Forum

now planned to treat the nation’s cities more comprehensively. Philadelphia would get ten pages of the magazine in July; that was Jane’s article. Cleveland would be next, and Jane—was she by now the magazine’s resident urban expert?—got that one, too.

Cleveland had plenty going for it, she wrote in the article that appeared in August, but its future seemed to stop dead at the city line; suburbanites wanted nothing to do with it.

It is hard for an outsider to understand why Cleveland as an organism, as an idea, fails to captivate the suburban imagination in the immemorial way of big cities. For Cleveland has individuality, and visually it is a stirring sight. It deserves neither to be thought of as a mere facility, nor to be snubbed. Inherently, it is anything but monotonous; industry-lined river and creek valleys slash deeply through its hills. Bridges, ore-loaders, stacks put their peculiar zing into the humdrum commercial and residential scene. Maybe industry cutting through the city is not “nice,” but from the freeway alongside or banks above, it makes a vista as exciting as the tumbled excesses of nature.

Jane went on to tell of the city’s lakefront plans, news of freeways and rapid transit, as well as proposed redevelopment of Garden Valley, which, she wrote, would “transform a desolate industrial wasteland and an enormous, steep, barren ravine into a neighborhood” of low- and middle-income housing. If she had doubts about any of this—as she might well have, for Garden Valley became an awful slum—they didn’t surface.

So whatever was going on in Jane’s fecund brain, it didn’t make for a wholesale break with the past. She had a good job. She was writing. Everything was fine. Except, everything wasn’t: Bacon’s Philadelphia remained a mental irritant, like a grain of sand in the eye that won’t wash away.

—

If during the mid-1950s you came for dinner at the Jacobs house on Hudson Street, the first thing you’d see as you came in, parked just off the kitchen, was a bike, wicker basket suspended from its handlebars. Come 9:30 or 10 weekday mornings, garbed in respectable office dress, sometimes even pearls, Jane would pedal it up one of Manhattan’s broad north-south avenues the two and a half miles to the

Forum

offices at Rockefeller Center. It was an era before bicycle lanes, helmets, and ten-speeds, much less messenger bags and fixies; navigating Midtown Manhattan by bike, especially for a middle-aged mother of three, was outlandish enough to earn Jane a place in her own magazine.