Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (32 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

Nobody cared what we wanted when they built this place. They threw our houses down and pushed us here and pushed our friends somewhere else. We don’t have a place around here to get a cup of coffee or a newspaper even, or borrow fifty cents. Nobody cared what we need. But the big men come and look at that grass and say, “Isn’t it wonderful! Now the poor have everything.”

“

There is a quality even meaner than outright ugliness or disorder,” wrote Jane in one of her most quoted passages, “and this meaner quality is the dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and be served.”

—

Death and Life

was not the work of a day. It was “much more difficult than I imagined it to be,” Jane would say. “I was filled with anxiety the whole time I was doing it,” occasionally tempted “to put everything into a garbage bag” and set it out for pickup. It was packed tight with ideas many of which traced back not to the few years of the book’s actual composition but, as we’ve seen, to 1955 and long before; some of Jane’s thinking harked back to her Columbia days. Set against the articles she wrote for

Forum

, the book was virtually unrecognizable, its flavor markedly different even from that of her 1958

Fortune

article. For most of her career, an article meant a few days or weeks of work, then on to the next one. Now, in late 1960, she was concluding a project that dwarfed by a factor of twenty or thirty anything she’d done before. “

This is the fourth draft of this damn chapter,” she wrote Jason Epstein on December 15, “and it probably needs a fifth and a sixth. I have forgotten how to write & this makes me very worried. Four more to go seems like forty more to go.” Just now, approaching the end, she was showing portions of the manuscript to Epstein, his assistant Nathan Glazer, and Chadbourne Gilpatric, each of whom responded with opinions, objections, and last-minute questions.

One editorial interchange concerned her last chapter, “The Kind of Problem a City Is,” the very strangeness of its title calling attention to itself as a separate species, set apart from the rest of the book. Jane took as inspiration an essay (appearing in the same 1958 report of the Rockefeller Foundation that listed her original grant) by retiring vice president Warren Weaver, a mathematician who had helped develop the philosophical implications of Claude Shannon’s famous 1947 paper on information theory,

a founding document of the digital age. Weaver’s focus was mostly on the biological sciences; Jane would apply his thinking to an intellectual regime, cities, which he’d probably never thought about at all. It seemed to her that Weaver’s breakdown of the types of problems with which scientists grapple summed up, “

in an oblique way, virtually the intellectual history of city planning.”

Weaver described, first, a class of simple scientific problems: you strike one billiard ball with another, at a particular spot, from a particular angle, and with a particular force, and you can predict in some detail what will happen. This was old-hat physics, explored before the twentieth century, relatively straightforward, mathematically navigable.

A second category of problem was one of “disorganized complexity,” which you might find on a giant billiard table cluttered with not one, or fifteen, balls but millions of them; no way, even in principle, could you trace the path of any one ball amid all that clacking chaos. On the other hand, you could probably come up with useful averages and broad patterns; you could approach statistically and probabilistically, for great numbers of balls, what you couldn’t for any one of them. This approach was applicable to a welter of real-world problems, from life expectancy tables to thermodynamics.

The study of living systems, Weaver observed, yielded to neither approach but rather fit a third category. “

What makes an evening primrose open when it does? Why does salt water fail to satisfy thirst?” These, Weaver’s own examples, were more complex by far than plunking billiard balls together. But they were by no means “disorganized,” and weren’t much illuminated by statistics. Rather, they were problems of “organized complexity”—in Weaver’s words, marked by “a sizable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole.”

Like, Jane now argued, a city.

How to understand, she offered as example, a neighborhood park, with its slew of interacting forces? The physical design of the park itself figures in. So does its sheer size. So do its users, who they are, when they use it, the pattern of the surrounding streets, and much else. You might wind up with a fine, well-used park, happy and safe; or one that proved barren and dangerous, unappealing to adults and children alike. Either way, the outcome didn’t depend on any one single factor; it wasn’t one of Weaver’s simple problems. Nor could statistics, maybe some crude ratio of open space to local population, shed much light. Rather, the problem occupied

Weaver’s third category, where, as with the evening primrose, numerous interrelated factors figured in. There was “

nothing accidental or irrational about the ways in which these factors affect each other,” wrote Jane. But understanding it required close-in, almost microscopic study that resisted, as she wrote in relation to a related problem, “easier, all-purpose analyses, and…simpler, magical, all-purpose cures.”

This was the

kind

of problem the city represented, the kind that the Ebenezer Howards and Le Corbusiers of the world didn’t see. For Howard, the city reduced to housing and jobs. For Le Corbusier, as Jane wrote, “his towers in the park were a celebration, in art, of the potency of statistics and

the triumph of the mathematical average.” With statistical techniques, the relocation of people uprooted by the planners “could be dealt with intellectually like grains of sand, or electrons or billiard balls.” But so crude an approach fell woefully short of real understanding.

Jane’s final chapter didn’t read much like the rest of the book. It read suspiciously like science. And Nathan Glazer, for one, was little sympathetic to it. “

I am somewhat allergic to talking about science in situations where a general intelligence and sensitivity are demanded,” he wrote Jane. She’d made too much of Weaver’s distinctions. He saw little value in them. Stick to more concrete arguments, he advised her. Maybe, he allowed, his was “an over-personal reaction to abstract and theoretical points,” but still, he hoped Jane would reconsider.

In retrospect, it shouldn’t be surprising that Jane turned now to science. Back at Columbia she’d relished her dips into biology, psychology, geology, and zoology. And what was her “method” generally in

Death and Life

but a careful, fine-grained

seeing

common to much of science? She emphasized less what cities were than how they worked; not the nature of a slum but how it got that way; process more than product. (In a note I found among her papers, she takes issue with a scholar’s assertion that “

the task of science is to lessen the pain of encountering the future by anticipating its problems.” No, it was not, she insisted. “The task of science is to understand how things work.”) She was not, of course, a scientist herself; she didn’t count galaxies or trace metabolic pathways for a living. But as a leading Jacobs scholar, the architectural historian Peter Laurence, would observe, even her earliest New York essays from the 1930s reveal a “deeper, protoscientific curiosity about the city’s underlying processes.”

Death and Life

, meanwhile, retained “

the freshness and immutability of scientific principle.”

We don’t know how much thought Jane gave Glazer’s suggestions. We do know that two days later, she fired back a reply: “

I very strongly disagree with you about the last chapter.” For one thing, she wasn’t making analogies to science, as Glazer had implied, but was discussing “methods of thinking and analyzing that are

common

to science and various other kinds of thinking, not analogous.” No, “that last chapter may take a while to sink in, but if and when it does, it will change planning more than any other idea” in the book.

The chapter stayed.

Of course, at this point it little mattered. By now, any issues Glazer and Epstein were raising (and on which they mostly deferred to Jane) could be seen as narrow, even technical. For the manuscript, all 150,000 or so words of it, was now all but done; whatever tweaks it would require over the coming months, its nature was fixed.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

was, Epstein weighed in, “

the most exciting book on city planning that I have ever read—and one of the most exciting books on any subject I have ever seen. I’m delighted with it and proud of you and I eagerly await the manuscript in its final version.”

On January 24, Jane wrote Nathan Glazer, saying,

“Here is chapter 22, the

last

! Now I am going out and getting two martinis. Maybe three.”

CHAPTER 13

MOTHER JACOBS OF HUDSON STREET

I

N 1961, A BLISTERING REVIEW

of

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

would dismiss its author, in its very title, as “Mother Jacobs.” Later, when Jane led the fight to block a highway backed by Robert Moses, he would declaim in a fit of pique that the only people who opposed it were “

a bunch of mothers.” Now, whatever else Jane was when she left her job at

Forum

in 1958 and set to work on the cities book, she was indeed a mother. Her three children, Jim, Ned, and Mary, were ten, eight, and three respectively. By the time the family left Hudson Street for Toronto in 1968—with

Death and Life

published to much acclaim and Jane a public intellectual and community figure of note—Mary was an adolescent, the two boys were men, and Jane had been a Greenwich Village mother for two decades.

In the fall of 1958, Jane was forty-two years old. It was the first time she hadn’t reported to work at a Midtown office since 1946, when she’d briefly freelanced from home. Actually, she didn’t work from home now, either, but in a rented office. Early on she’d realized, as she wrote to Chadbourne Gilpatric the following July, that she needed “

a room to work in, where I am uninterrupted by people, telephone, etc.” She found one on

Bethune Street, a five-minute walk from home, on the second floor of an old 1830s-vintage rooming house that shook to the rumble of trucks bound for the West Side Highway. It was Bob who arranged it, for $45 a month, and when Jane moved in, rumors spread that, as son Jim would tell the story, she was “a kept woman.” Later, the building was sold out from under her (to a literary agent), so she had to find another place, and

she wound up in the Sheridan Square building she mentioned in

Death and Life.

Mary would remember that “stark little room” of an office, with its shouts and thumps of boxing from the gym next door.

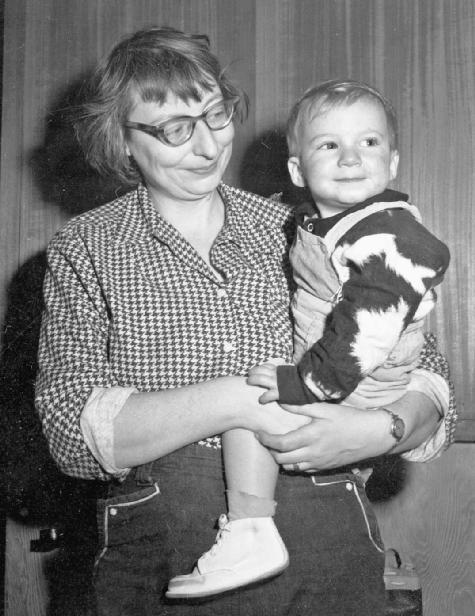

Jane and her son Ned, about 1952

Credit 17

Meanwhile, Jane paid for the help she needed at home. During these years, up until 1960 when she died, Glennie Lenear, the woman whom Jane had hired after Jimmy’s birth, was a conspicuous figure in all their lives. When she was still at

Forum

, Jane’s routine was to wait until Glennie arrived in the morning, then haul off on her bike for Rockefeller Center. Glennie cared for the kids when they got home from school and prepared their meals, staying until Jane got home at around six. “She looked after me in the nicest way,” says Mary, who, groping for words, opens her arms wide, hugging Glennie’s remembered girth fifty years later. “She was wonderfully capable. I just loved her. She was like another mother.” Ned walked Mary to kindergarten, Glennie picked her up. With school about to let out for the boys, she might be heard to groan, “Oh, it’s time for those devils to come home.” Jimmy and Ned could be a handful; their cousin Jane, Jim Butzner’s girl, remembers them as “wild, rambunctious, mischievous,” her own visits to the house welcomed by Glennie

as those of, finally, “a girlie girl.” The rented office and Glennie’s ministrations over many years (which Jane acknowledged in

Death and Life

) let her keep her writing time sacrosanct.

Jane cooked for Bob. She read to her children before putting them to bed. She could be counted on to get what the kids needed for school or play, to head up to

Macy’s to buy ankle straps for the kids’ ice skates or a corduroy jumper for Mary. Sundays, she and Bob took the children to church, St. Luke’s Episcopal, a few blocks down Hudson Street. Jane wasn’t religious. She felt scant attachment to the Presbyterian church of her childhood. She saw people of a spiritual bent as misguided. And yet, she wrote one correspondent, services at St. Luke’s “gave me the satisfying, in fact inspiring feeling that I was a link in a long, sinewy, living human tradition of being.” This worked for Jane, anyway; for the kids, who attended Sunday school, not so much. A “vaccine to stave off religion,” is how Jim came to see their Sundays at St. Luke’s. In the end, seen through a liberal-minded enough lens, Jane was just another American mother, doing her parental best.