Fail Up (19 page)

As I've frequently said and written: When we make Black America better, we make all of America better. No matter what nation we call home, all of us celebrate our true humanity when the least of us are economically, socially, and spiritually uplifted.

Justice for all

Service to others

Love that liberates

This is the diversity imperative that will truly make America a nation as good as its promise.

T

he phone call came every year for 15 years: “I know your life is moving along, but I know you, Tavis. I know you are not feeling complete about this. You've got to finish. If not, it's going to come back to haunt you one day.”

It was Ms. Dorothy, my counselor from Indiana University. She knew that I had left the university in my senior year without completing my degree. Ms. Dorothy had been keeping up with my career. Even though I was on national radio and TV, she worried that one day my reputation might be damaged if it were ever discovered that I hadn't “officially” graduated.

“I don't want you lying,” Ms. Dorothy usually continued. “We can do it by correspondence, but I want you to finish. You're too close, and your future is so promising.”

Fortunately, I hadn't told any lies. Interviewers didn't probe the “attended Indiana University” line on my résumé. My ascension in media was based on previous jobs. I went from local media to national media in steady succession.

Yet Ms. Dorothy did indeed know me. I didn't feel complete without the degree. Not because I didn't have it, but the reason why I didn't have it was what bothered me. I paid a huge penalty for backing someone into a corner and failing to save space for grace.

Finishing the Task

“Once a task you have first begun,

never finish until it is done.

Be the labor great or small,

do it well or not at all.”

â

BIG MAMA

I intended to follow Big Mama's sage advice, but the “labor” was indeed great.

As my three-month internship in Los Angeles came to a close, I found myself deeply in love with the city. I started telling friends I wasn't going back to Indiana. I'd transfer to UCLA, USC, or anywhere in California to finish my senior year.

Somehow, Mayor Bradley got wind of my plans. He called me into his office:

“Tavis, you're going to go back to school, and you are going to get that degree,” he said resolutely. “If I had known that this internship would cause you to not finish your education, I wouldn't have let you come.”

The mayor didn't completely burst my bubble though. He offered a deal: Once I finished my education at Indiana, he'd have a job waiting for me after graduation. How could I refuse? There weren't many of my classmates who had a prestigious job lined up a year before they graduated.

I went back to Indianaâbegrudgingly. After my internship in fast-paced LA, Bloomington seemed as slow as frozen molasses. My parents, who I always believed would grow old together, were embroiled in a bitter divorce. I was burnt-out, tired, and depressed, but determined to finish the task.

My mood was already sour the day one of my teachers popped a quiz on her students. The classroom wasn't your typical, spacious lecture hall; it was so small that the hundred or so students could barely turn without bumping noses.

Two days later, the teacher returned our graded papers. I missed only one or two questions, but there was a circled, red “F” at the top of my paper, with a handwritten message from the teacher: “Next time, keep your eyes on your own paper.”

I hadn't cheated. I was livid.

“What is the meaning of this?” I stood and shouted.

“It's self-explanatory,” she quipped; “keep your eyes on your own paper.”

Oh, it was so on!

With my honed debating skills, I reamed her. Like F. Lee Bailey or Johnnie Cochran, I relentlessly deconstructed her defenses. She insisted she saw me cheating. How is that possible? We were packed in the classroom like sardines! How could she tell who was cheating or who was simply turning their heads? If I supposedly cheated, I argued, she was obligated to call me out at that time, not two days later.

“Who else cheated?” I spat. “For all I know, you could have just picked me out for other reasons and given me an âF' to justify your biases.”

“W-w-what do you mean?” the teacher stammered.

“What part do you not understand? I'm the only Black person in this class.”

She stammered, broke into tears, and grabbed her things as she dismissed the class and bolted out of the room.

Perhaps I was taking my frustrations out on that teacher. Although she certainly deserved to be checked, I left no wiggle room for a graceful retreat.

If I had, maybe it wouldn't have taken me 16 years to get my degree.

What Goes Around â¦

There was no reprimand for my outburst. In fact, after hearing both sides, the dean told the teacher that she hadn't handled the situation correctly. If I had cheated, she was obligated to inform me at that time. He made the teacher restore my grade.

After the humiliated teacher left his office, the dean asked that I stay behind.

“I highly recommend you switch out of that class,” he said. “I have the feeling this tension is not going to get any better. This course is a requirement for you to graduate. Don't put yourself in a bad situation.”

Feeling highly justified, I thanked the dean for his advice but insisted I had done nothing wrong and didn't plan to drop the class. She was wrong, not me. If anybody should drop the class, it should be the teacher, I insisted.

The rest of that semester was torture. I had an internship in the chancellor's office, debate team duties, and several other challenging classes; the conflict between my mother and father also unsettled me. I was bored with the class in which I had the confrontation, and I skipped the majority of those classes.

At semester's end I was in trouble. I absolutely had to pass the student teacher's class to graduate. Since I skipped the class, I knew none of the material. The course was a requirement, but all I needed was a pass/fail grade. In other words, a “D-” would do. I sweated through long nights of intense study to get ready.

I took the test and flunked it. Miserably.

Now I was backed into a corner. I had to go see the teacher and share my woeful tale. I told her about the job waiting for me in California that I just couldn't miss. I begged her to let me take another exam or make it up in some way.

“Is there anything you can do?” I pleaded.

“Anything I can do?” she said, unmoved, defiantly looking into my eyes.

“Why, Mr. Smiley, surely you're not asking me to inflate your grade? You of all people aren't asking me to give you a grade you didn't earn?”

She took so much joy and delight in the turned tables. I can't say I blamed her. The first week of the semester, I got her in trouble. The last week, there I wasâin troubleâbegging her for a “D-,” anything but another big, fat “F.”

Apparently done with the conversation and me, the teacher pointed to my test paper: “This is what you got. This is the way it's going to be. Sorry, can't help you. Bye, bye.”

Thank You, Ms. Dorothy

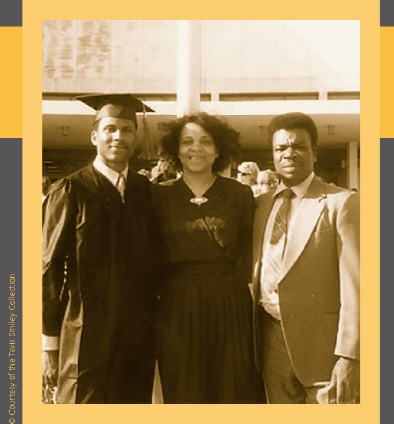

Luckily, I had enough credit hours to participate in the graduation ceremony that May. At least I could look like I was graduating on time. My entire family came to the ceremony, but I didn't have the courage to tell them I hadn't actually completed my degree. I'd have to deal with that unfinished business later. In California. Mayor Bradley was expecting me to start on a certain date, and I was determined to show up for work on that day.

After arriving in LA, to my surprise and disappointment, I had to wait more than a year to rejoin the mayor's staff. I was stuck in California hustling just to eat and pay rent. Going to summer school to earn the credits I needed to get my degree was impossible.

The mayor's staff assumed I had a degree. But over the years, the guilt was eating at me. I attended my siblings' college graduations, knowing that neither they nor Mama and Dad were aware that I wasn't a certified graduate. What made this all so ironic was that I was the one paying most of the bills for my younger siblings to attend college, and they had degrees conferred on them while I had still not completed all of my course requirements! Interestingly, I had received a number of awards and recognitions from colleges and universities for my societal contributions before I had secured my bachelor's degree in public policy from Indiana! But even the high honor of being recognized by some of the nation's top schools didn't alleviate my guilt of not having completed the requirements to graduate.

But what really got to me even more was Ms. Dorothy. She called again, 15 years after I had left Indiana, to say she planned to retire that year:

“I do not intend to retire without you having your degree,” she said.

That was it. I made arrangements to complete my studies from Los Angeles. When I finished the course work months later, I was told the degree would be mailed to my home.

Dr. Kenneth R. R. Gros Louis, the chancellor I interned with in my final year at Indiana, had a summer home in Santa Barbara, California. One day, he called and asked if I could meet him for lunch while he was on the West Coast. At the conclusion of our lunch, Dr. Gros Louis said he had something for me. He stood, reached into his briefcase, pulled out my degree, cleared his throat, and ⦠well, he described it best in the March/April 2004 edition of

Indiana Alumni Magazine

:

“I said, âBy the authority vested in me, through the president and the board of trustees, I'm pleased to confer upon you your degree.' And he got quite teary. He didn't cry, but it was a much more emotional moment than I thought it was going to be. It was a nice meeting and a long conversation, and I was very impressed with his intelligenceâand always have beenâbut also the warmth of his personality.”

After Dr. Gros Louis gave his formal conferral presentation, people started clapping, I started cryingâit was a delightful, emotional moment on a beautiful day in sunny Southern California.

Indiana Alumni Magazine

did the cover story with a picture of me holding my newly conferred degree. The caption read: “Tavis Smiley finally gets his degree 16 years later.” I sent it to my parents. Albeit 16 years later, they finally learned their son was indeed a college graduate.

So Right Can Be So Wrong

We've all encountered people who push our buttons. They wrong us, insult us, and sometimes embarrass us in public. Their comeuppance is deserved, we rationalize. If they push, we can feel perfectly justified in pushing back in kind, right?

Maybe not, especially when we consider the consequences. Sometimes you can be so right and so wrong at the same time. Millions of Americans have lost their jobs in the past few years. I'm sure some who were unceremoniously escorted off the job felt justifiably betrayed, demeaned, or humiliated. Wars start because leaders often leave no room for compromise and their opponents have no graceful exit. Many individuals in relationships who feel wronged or abandoned react violently, and too many kids use guns to settle perceived disrespect.

Yet the way we leave our last job affects how we get the next one. Payback may feel great at the time, but as my situation demonstrated, what goes around sometimes comes back around. There are better ways to diffuse volatile situations than humiliating an adversary. Instead of excoriating the teacher in front of the class, I should have gone straight to the dean. As a third party, he could have helped us respectfully detach from our emotions.

In the CBS.MoneyWatch article, “Laid Off? 7 Rules for a Graceful Exit,” Amy Levin-Epstein offers useful tips that apply outside of job-loss situations. She suggests we avoid taking slights personally, remain cool in confrontational situations, and find “safe places” with therapists or friends where we can discuss feelings of humiliation, shame, and terror.