Falling to Earth (34 page)

Authors: Al Worden

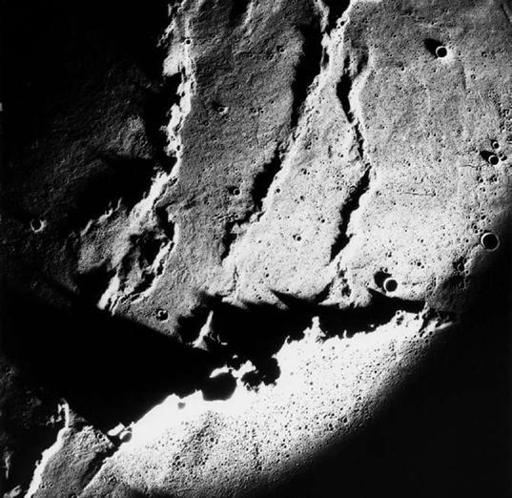

With no atmosphere, the line between day and night was strikingly distinct. Mountains cast long slashes of blackness across the landscape, and features stood out as if I had placed a flashlight against a rough stucco wall. I was fascinated by the starkness of the peaks. I loved to take photos in these shadowy regions—and not only because it helped the scientists. Back on Earth, they could use the shadows to measure the height of lunar features. But there was also a drama and beauty in these locations, and I concentrated much of my photography there.

Streaks of light would create alternating light and shadowy waves that once again stretched and seemed to billow and flutter as I curved into blackness. I felt like a sailor crossing a dark ocean. I knew photos could never capture what I observed. Neither can these words.

Once in darkness, I tried to take low-light-level photos of astronomical objects. With the moon cutting off light from the sun and Earth, the blackness was total. I would put my camera in the window and try for a ten-second exposure, using very fast film. It was tough to hold the spacecraft steady. I spent a lot of time working to keep

Endeavour

motionless, but in the end I decided it was impossible for more than a few seconds at a time. The spacecraft just wasn’t that delicate to maneuver. But I still took some great photos.

Endeavour

had one window with no ultraviolet shielding or any other protection. Made of quartz, it was absolutely clear. I’d been warned never to look out of that window without sunglasses or be caught in a direct sunbeam. It could have ruined my eyes and burned my skin. But that window was invaluable for photos when

Endeavour

was in complete darkness.

I was fascinated by the dramatic long shadows where the sun was rising or setting on the moon

.

As I would be the first person to fly over the Aristarchus crater, scientists had asked me to study it closely. Astronomers thought they had seen reddish glows there, suggesting the crater was volcanically active. It was such a pale, smooth, almost mirror-like crater that even in shadow it looked as if it was gleaming in sunlight. “Looking at Aristarchus, a little bit in awe,” I later told Karl.

I didn’t see any glowing, but other instruments picked up possible traces of seeping radioactive gases.

Something

interesting was going on there. I hoped my measurements would help scientists puzzle it out.

Most of my observations grew out of my extensive training with Farouk. But the perception of human eyes allowed me to note subtle differences from Farouk’s photos and theories almost right away. For example, as I flew over the immense Tsiolkovsky crater, I saw that the enormous central peak was a little higher and the outside rim better defined than we had imagined. In photos, the smooth, lava-filled crater floor looked darker than its surroundings, but with my own eyes I could see that it was different only in texture, not color.

The crater was so vast that when I crossed it I could see little else. The central peak rose like a Swiss alp, a towering pale slab of rock surrounded by boulders hundreds of feet wide. Gazing closely, I could see details of rock layers no camera had ever captured. It looked like something had smashed into the moon eons ago like a stone into a pond, leaving a rippled crater, a smooth basin of lava, and a central peak rebounding out of the lunar depths. It reminded me of a bright island rising from dark, smooth waters.

Gliding over Picard crater, I could see delicate layers of lava, like rings on a bathtub, all the way down the crater walls to the bottom. They alternated between thin light and dark bands. This beautiful effect was hard to capture on camera, but I could observe with my eyes and describe it in detail.

The moon was overwhelmingly majestic, yet stark and mostly devoid of color. Every orbit, however, I was treated to the sight of the distant Earth rising over the lunar horizon.

In my entire six days circling the moon, no matter what I was doing, I stopped to look at the Earth rise. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen or imagined.

Our planet was the only place with color—distant blues, browns, and greens—all focused in one tiny globe. Ethereal and small, it shone in the deep black of space, much brighter than the full moon appears from Earth. Photos of Earth from the moon have a flat quality, but looking at it with my own eyes Earth felt alive and captivating. It seemed to beckon like a warm refuge. More than a gorgeous sight, it was home.

Earth had seemed limitless when I had walked out on launch morning. Now it was a faraway sphere, so small that it was hard to believe everything I had done, everything I had seen, had happened down there. I now felt apart from Earthly affairs in a way I can’t describe. Perhaps you have to go to the moon to feel it. But I could see that Earth was truly finite. That distant ball could only support so many people and contain so many resources. Once it is gone, it’s gone. If humans didn’t unite and organize their lives, I pondered, we’d be in trouble. Our parochial interests, whether religious, economic, or ethnic, are all best served by trying to keep our tiny island in space livable. In fact, to live any other way suddenly felt like insanity to me.

I never grew tired of watching Earth rise above the moon

.

It sounds cliché to write, and perhaps a little surprising coming from a military officer, but the experience was mind altering. And when I experienced the feeling for myself, I knew in my gut it was the truth. Ironically, I had journeyed all this way to explore the moon, and yet I felt I was discovering far more about our home planet, our Earth.

As the days passed I watched the Earth change phases just as the moon does from Earth. When I arrived, the Earth was about half full, but it gradually diminished to a delicate crescent. Only when I looked back at the Earth rising did I understand how far I had traveled. I was isolated, with only the radio to stay in touch. If I thought about it too much, it was almost a little scary—not the isolation, but the sheer distance. We had a long journey back.

Farouk and I had worked on something special for every time I saw the Earth rise. I’d noticed that, to the public, guys flying around the moon seemed kind of ho-hum, nothing exciting. How could I make it interesting? I talked about it with Farouk, and we decided the best way might be for me to say something interesting every time I came back into radio contact. We came up with a phrase that we thought might grab everyone’s attention: “Hello Earth, greetings from

Endeavour.

” Farouk wrote it out for me phonetically in nine foreign languages: Arabic, Chinese, French, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, German, Spanish, and even Russian. Along with English, I’d have ten different ways to say hello to the citizens of our planet and make the point that the Apollo program was for the whole Earth, not just America.

It worked. I tried to transmit a different variation on every solo orbit, and the world press paid a little more attention.

I had brief opportunities each day to talk to Dave and Jim down on the surface. It sounded like they were toiling through an impressive science exploration schedule of their own. I could even look down into the deep rille while passing over the Hadley plain and see enormous rocks in the canyon at the exact same moment Dave and Jim were parked at the rim in their rover.

“Pretty spectacular up beside that mountain, I bet,” I asked Dave one time.

“Oh man, it was super, just super,” he replied. “We’ve got some great pictures for you.”

“I hope I’ve got some good ones for you, too,” I happily replied. It was great to hear from them.

But I guess Jim was feeling grungy from all that moon dust. “Hey, Al, throw my soap down, will you? And my spoon,” he radioed. “I really need my soap.”

“Don’t mind if I use it, do you?” I responded, teasing him a little.

“Save me a little bit!” he pleaded in return.

Dave and I then bantered about saving the soap until we were all back in lunar orbit again. The conversation was lighthearted, but once again we were reassuring ourselves that everything would go to plan.

Falcon

would lift off and rendezvous with me in space. We were going to survive and see each other again.

I looked for Dave and Jim every time I flew across the landing site. It was never easy to find them, and usually I only caught a quick reflection from

Falcon

before I lost them. And yet I felt closer to them than the people on Earth I was talking to all the time. It was reassuring to chat briefly every day and confirm I was still there for their return trip. “Save us some food!” Jim quipped as I sailed overhead.

While they were roaming the surface, I was hanging in weightlessness, so I needed to exercise. I had a small cylindrical device called the Exergym. A nylon rope wove through a series of friction pulleys, so when I pulled on it the friction created tension that I could exercise against. It was a great idea, but the damn thing didn’t work.

We hadn’t even reached the moon when the nylon started to fray. It heated up when we used the device and stretched the rope into useless threads. This was puzzling, because crews before us had taken it and said it worked fine. I suspected they hadn’t used it much.

I still needed to exercise, so I improvised. With the center couch removed, I could hold on to the two struts in the middle of the spacecraft and push against them. I could do knee bends and run in place with my legs freewheeling in air. I felt my heart rate rise and could watch the attitude indicator and see the entire spacecraft rocking back and forward.

I’d been looking at the Littrow region of the moon a lot, because scientists were curious about the darker soils there. Were they evidence of volcanic activity? On one pass, I spotted something unusual. “There are a whole series of small, almost irregular-shaped cones,” I reported, “and they have a very distinct dark mantling … It looks like a whole field of small cinder cones down there.”

Unlike craters created by meteorites, cinder cones build up as debris is pushed out from a volcanic vent. I was seeing features that met the definitions I had studied.

“They’re somewhat irregular in shape,” I continued. “They’re not all round … and they have a very dark halo, which is mostly symmetric, but not always, around them individually.”

Mission planners had told me I wouldn’t be able to see features that small. But that wasn’t true. If I stared hard at a fixed point, it was tough to resolve. But if I swept my eyes around the general area, I could pick up a lot more detail.

As I described these funnels surrounded by dark rings, the geologists back on Earth grew excited. So much so that the last Apollo lunar mission, Apollo 17, was targeted for the Littrow region. That mission didn’t reach any cinder cones. Instead they found an impact crater that had punched through the surface, throwing up an unusually dark ring of subsurface volcanic ash and bright orange glass beads. Good enough.

My work days were busy, but I was floating around so I didn’t burn up much energy. The ground had assigned me seven or eight hours to sleep. I found I only needed three or four. It wasn’t because I was nervous; it was more because I was excited. I had a lot to do. I didn’t bother telling mission control I was awake. I used some of the time to finish up experiments and take photographs, but I also had hours of free time around the moon to just look out, marvel, and think.

I orbited alone in a detached, eerie silence, my spacecraft on a smooth trajectory. When I flew jets back on Earth, I was used to little bumps as I cruised through air and the roar of the engine. Here there was stillness and peace. It was more like riding in a hot-air balloon, drifting with no sensation of motion. I felt like an imaginary alien might when visiting Earth in a UFO, that this was not my planet. I was not from here, and perhaps not even supposed to be here. I was spying on an alien place.

The only noise came from pumps and fans running in the background, which I only noticed if something did not sound right. Just like driving a car, you only snap alert when you hear something unexpected. Since my life depended on this machine, I was hyperaware of unusual sounds.