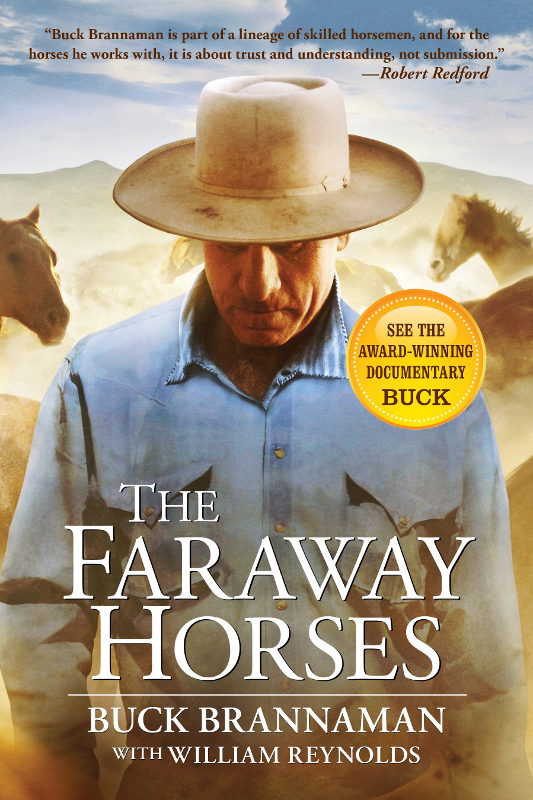

Faraway Horses

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

The Faraway Horses

The Faraway

Horses

The Adventures and Wisdom of One of

America’s Most Renowned Horsemen

Buck Brannaman

with William Reynolds

Lyons Press

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of The Globe Pequot Press

Copyright © 2001 by Buck Brannaman and William Reynolds

First Lyons paperback edition, 2003

All photos are from the personal collection of Buck and Mary Brannaman unless otherwise stated.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

ISBN 978-0-7627-9608-3

The Library of Congress has previously catalogued an earlier (hardcover) edition as follows:

Brannaman, Buck.

The Faraway horses : the adventures and wisdom of one of America’s most renowned horsemen / Buck Brannaman with William Reynolds.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-58574-352-6

1. Brannaman, Buck. 2. Horse trainers—Wyoming—Biography. 3. Horse whisperers—Wyoming—Biography. 4. Horses—Training. 5. Horses—Behavior. 6. Human-animal communication. I. Reynolds, William, 1950– II. Title.

SF284.52.B72 A3 2001

636.1′0835′092—dc21

2001038854

[B]

A

good idea for a book starts out like a young horse—lots of promise but it’s all in the follow-through. Over the four years we’ve worked on this book, there have been some significant people who have entered our lives and given us counsel on this project. Special thanks goes to Betsy and Forrest Shirley, Tom Brokaw, Robert Redford, Patrick Markey, Bernie Pollack, Kathy Orloff, Donna Kail, Craig and Judy Johnson, Suzanne and Paul DelRossi, John and Jane Reynolds, Lindy Smith, Verlyn Klinkenborg, Chas Weldon, Joe Beeler, Elliott Anderson, Adrianne Fincham, Steve Price, and Jesse Douglas. At The Lyons Press, we thank Tony Lyons for seeing the vision and Ricki Gadler for putting up with us.

Our biggest thanks goes to the two women who believed in us all along—Mary Brannaman and Kristin Reynolds.

—Buck Brannaman and Bill Reynolds

M

Y

“

LIFE RELATIONSHIPS

” with horses started after childhood, but I had wanted a pony as far back as I can remember. As a child of the 1950s and of a father who was a pioneer in television, I was never unaware of the impact of the TV western in my life. It fed my need for horseflesh at an addictive rate. This ultimately alarmed my parents. We were urban-bound and landlocked on three sides, so to slip a pony into the backyard would have been quite impossible without the fabric of the neighborhood coming apart at the seams. Of course, I knew and actually understood the problem, but I refused to let the pressure off my parents. They tried valiantly with riding lessons and trips to dude ranches during school vacations, but it was never enough.

My first horse, unlike the Will James book of the same name, arrived during my early twenties. She was a young liver chestnut Quarter Horse mare with a flaxen mane and

tail and was, if in my eyes alone, perfect. I should have sensed some trouble when it took us three hours to load her into a neighbor’s trailer. It required all sorts of ropes and pulleys, with lots of yelling and screaming, but we got her in. My adventure had begun.

* * *

I met Buck Brannaman in 1985. He was at a local arena in Malibu, California, and to see a Montana cowboy work with a bunch of hunter/jumper riders was a sight I didn’t want to miss. I had heard a little bit about Buck from my friend Chas Weldon, the legendary saddlemaker in Billings, Montana. Chas spoke quite highly of him, and said he was designed to ride horses. When I first saw Buck, I knew Chas was right. Buck is three-quarters leg, the kind of rider who can touch his heels under the belly of a horse at the lope. I later found out that he was rather short going through high school, but grew a full six inches in his senior year, which landed him on the basketball team. Is he tall? The man could hunt geese with a rake.

The first time you see Buck ride is a moment of lasting impression. It isn’t just the way he sits a horse, although that in itself is rather impressive. As he rides, he seems to disappear into the action. People speak of “becoming one with” something. Buck doesn’t ride a horse, he merges with it. The essence of this merger is a friendly takeover.

I’ve seen him ride hundreds of different horses, and it happens every time. There is a moment when these two beings open doors to each other and communication happens.

He creates an environment—unique to each horse he rides—that enables the two of them to work together. It still astounds me every time I see him ride a new colt. Each one is different, each is unique, and that’s how he treats them. If this sounds like a good way to be with people, you’re catching on.

Buck has done more good for families, as well as their horses, than any man I know. He does this by getting people to slow down and listen: listen to their horses, their kids, their husbands, and their wives. He is about respecting others, whether they are people or horses—they’re all the same to him.

T

HE

F

ARAWAY

H

ORSES

opens a door into the life of Buck Brannaman. He has chosen to open it and let us all in. In his own words, he takes you through his difficult childhood and his youth growing up in a foster home. It is the story of a life of discovery, of pain and tragedy, and of finding one’s way and then giving back to the ones who saved him. For Buck, it was horses. The horses saved his life.

These stories make up a significant young man’s life, a young man who changes for the better the lives of every horse and rider he comes in contact with. I am proud to call him my friend and to have worked on this book. Quite simply, we need a lot more like him.

Bill Reynolds

Santa Ynez, California

2001

T

HE STORIES IN THIS BOOK

are scenes from the private movie of my life. They have helped me understand the big picture, and they have influenced directions I’ve taken since the events happened. In many ways they have affected the way I work with certain horses. I know they have influenced me in the way I deal with people, but horses have always meant a certain level of consistency in my life. They respond with all their being. All they know is honesty.

On my way to a horsemanship clinic I was putting on in Ellensburg, Washington, I decided to make a little detour through Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. It’s a peaceful town, and its beauty is magnetic. I can see why so many people have come here to retire.

I sat looking out my truck window, with my horses standing quietly in my trailer, at the old house at 3219 North Fourth Street. That’s where my older brother, Smokie, and I lived with our mom and dad for a few years in the mid-1960s. Seeing it more than thirty years later brought back a flood of memories.

The shed, not much more than an overhang to the back of the house, made me think of milking cows there, and how, in the eyes of a kid just four feet tall, that pitiful little shed seemed like a huge barn. When I saw the basement window, I remembered struggling to drag a hose through it so I could water our horses, cows, and pigs, and how more often than not that hose would hang up at the hose joint a few feet short of the stock tank.

The yard was where Smokie and I learned to ride and spin a rope, little knowing we would soon be performing on TV and at rodeos and fairs around the country as “The Idaho Cowboys, Buckshot and Smokie, from Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.”

The number on that beat-up old mailbox stared back at me: 3219. I was tempted to knock on the door to see who lives there, and maybe walk around a little.

So many memories. So many times the ambulance would arrive at the house to collect my mom because she was having a diabetic reaction. And so many times our neighbors would call the sheriff because old man Brannaman was working his kids over again.

But today, I’m no longer afraid, not even of the memories. In a strange, almost melancholic way, it felt good to be here. Who would have thought that one of those “Idaho Cowboys” would grow up and have the joy of working with so many people and their horses, trying to help create relationships based on trust? It’s ironic. Trust was something I had in short supply as a youngster.

Ride with me now, and I’ll tell you some of what’s happened along the way. It’s been kind of bumpy, but well worth the trip.

Things are so good for me now due, in large part, to my wife, Mary. It is to her, to my family, and to the Horse that I dedicate not only this book, but my life.

Thank you for your interest, and may your life be filled with good horses.

Buck Brannaman

Sheridan, Wyoming

2001

Growing Pains

I

’

M ABOUT HALFWAY THROUGH

a year’s worth of giving horse clinics around the country. I love what I do, but I’m away from my family for long stretches at a time, and that’s tough. My wife, Mary, stays at our ranch with our three daughters doing all the things a working ranch demands. Leaving them is hard. My youngest daughter still asks, “Why, Daddy, do you have to go and ride the faraway horses?”

So off I go for three to four days at each stop, meeting people and their horses, helping them get along and get things done together. Then I leave. I’m always starting, but I’m always leaving. When the expressions of the horses and the people start to become more pleasing to the eye, I have to say so long.

It’s hard to explain how other people’s horses could save your life, but that’s exactly what happened to me. I’ve been thinking about this quite a bit lately.

Today my horses and I rolled into a clinic in North Carolina. It’s a fall day, and the sun is just up. It’s just past that time in the early morning when you can close your eyes, turn around, and pinpoint the first fingers of the rising sun. I love that time. Everything starts fresh from that point on: the day, the horses, and the people. It’s a quiet time, as well.

I talk all day for a living, so I do appreciate quiet. I get to feed and saddle horses in the quiet. The only sounds are those of the horses as they eat. There is a wonderfully predictable sameness to this scene, yet there is a newness that seems to permeate each first day of a clinic. I can feel the possibilities. It’s a reassuring constant. The idea of constancy is something that I’ve valued ever since I was little, because it wasn’t there much then.

I was born in 1962, in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, but I grew up in Idaho and Montana. My family lived in California for a little while, but by the time I was two years old we were living in the house on North Fourth Street in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

Given all that happened when I was little, the geography probably saved me as much as the horses did. The populations of Idaho and Montana are about the same as many small cities in this country, so you can imagine how small some of the towns in these states can be. Those stories you hear about towns being only “a bar and a post office” are true in many cases.

My dad, Ace Brannaman, was a talented man who had many jobs. He was a union cable splicer, and he worked on

construction crews building steel towers carrying power lines from the hydroelectric dams that were being constructed across the West and up in Alaska. He had a saddle and boot repair shop, and he was a private security cop for a while. Then he worked in a sheriff’s department as a deputy, which is kind of ironic when you look back at some of the things he did later on in his life.

My mom, Carol Alberta Brannaman, worked for General Telephone and Electric in Idaho, then as a waitress when we moved to Montana.

I went through a bunch as a little guy, and I can tell you there were times when I wondered if my brother and I would make it. I can remember looking up at the sky and, however simplistic it may seem now, wondering if there was a God up there. I’m sure at times we all ponder whether or not there’s a God. I find myself asking “big” questions when I’m driving or riding alone on horseback, and I’m here to tell you there is a God; if you don’t want to call Him that, call Him—or Her—what you want.

I was thinking about this quite a few years ago when Mom was still alive. She had diabetes, and it was real serious then. Medical science didn’t have much luck controlling diabetes in those days, and even though she gave herself insulin shots, she’d been in and out of the hospital a number of times.

Dad was working in Alaska, and my older brother, Smokie, and I were at home in Coeur d’Alene with her. I

was five years old, the same age as my daughter Reata is now. Late one night, Smokie and I heard something that woke us up. My mother was having a diabetic reaction, going through the stage of delirium that typically precedes a coma unless treatment is given right away. We ran into the bedroom, terrified. Mom was having a hard time. Smokie was only seven, and as he was trying to settle her, he hollered for me to run into the living room and call an ambulance.

I raced into the living room, but the phone was up on a railing, and I couldn’t reach it. As I was scrambling up a chair back, the phone rang. I still couldn’t reach it, so I grabbed a towel from the stove in the kitchen and snapped the receiver down from its perch. Scared that my mom was going to die, I yelled into the receiver, “I don’t know who you are, but my mom’s going to die if you don’t help me. We need an ambulance because my mom’s a diabetic.” And then I stood up on the chair and hung it up.

The call had come from an old gentleman named Mr. Thompson. The Thompsons were probably the only black family in Coeur d’Alene in those days. Mr. Thompson had come to build a life for his family by running a dairy herd on the backside of Lake Coeur d’Alene. My dad had about seven years of vet school when he was a young man, and when he was home from a construction job, he ran sort of a black market veterinary service. He’d pull calves, and doctor cattle, and sew up horses for people. Mr. Thompson had called to have a calf pulled.

When I told Mr. Thompson to call the ambulance and then hung up, I had no idea who I was speaking to. Of course, he called the ambulance and sent it to our house, and within just a few minutes it arrived. The paramedics took my mother to the hospital, and Smokie and I were taken to the neighbors and stayed the night. After a few days of worry, my mom was home, and everything was fine again.

It was uncanny how the phone happened to ring just as I’d gotten to it. If I’d picked it up a second sooner, Mr. Thompson’s call would have been cut off.

Timing is everything.

Timing was always a part of my young life. Timing and practicing. My entire youth was spent practicing. Not the piano or tennis, but rope tricks.

As a young man, my dad admired the famous trick roper Montie Montana, and he became infatuated with Montana’s life. After returning from World War II, he realized he would never be a Montie Montana, but he decided that his boys would be. He would live vicariously through Smokie and me—Dad figured “Buckshot” and “Smokie” would sell better than Dan and Bill, so I became Buckshot and Bill became Smokie.

Dad pushed us real hard. My brother and I would practice for hours each day. We had the choice of practicing rope tricks or getting whipped. After just a few whippings,

we sorted out pretty quick that practicing our rope tricks was the wise choice to make.

The reward was to travel around the country and perform. We all went as a family, and Mom would hover over us making sure life went on as normally as possible. Although I enjoyed the audience’s applause and attention, there were days when we’d have given anything to go out and play baseball. We did a bit, but most days consisted of getting on a horse and practicing roping.

I learned to ride when I was three, about the same time I started practicing rope tricks. Dad got Smokie and me some gentle horses, put us on, and away we went, taking easy rides around the yard. My dad could ride a little bit, but he just didn’t seem to have talent for working with horses. I wouldn’t say that he was abusive, at least not all the time, but he didn’t have feelings or compassion for horses. He was of the old school, like a lot of people were then, and looking back, I just don’t think he knew a hell of a lot about horses. His folks were farmers—he had been raised on a farm in Indiana—so he never really learned much about working with horses.

Our first performance as trick ropers was two years later on a Spokane, Washington, TV talent show called the

Starlit Stairway.

It was on Channel 6 and was sponsored by Boyle Heating Oil. A couple of little girls sang the jingle for Boyle Heating Oil, and I thought they were the most beautiful girls I’d ever seen. Granted, I was only five or six years old, but I guess I must have had an eye for the ladies even then. I thought they were big stars because I’d see them every week on TV.

Buck practicing his blindfolded routine. This picture was featured in a story about Buck and his brother that ran in the newspaper

Montana Standard.

The talent was mostly local kids, tap dancing, singing, or playing musical instruments. During the auditions, there was a girl ahead of us tap dancing. She had her long blond hair all done up in curlers, and as she was dancing this little

routine, the curlers started falling out of her hair almost in time with the music. I was just a little guy, and I thought that was the neatest thing. I couldn’t imagine how they had done those curlers up so they could fall out in perfect time like that, and how she didn’t run out of curlers until the dance was over. The girl was so embarrassed she started crying. I wondered why in the world she would be crying after such a nice performance.

When Smokie and I did our rope tricks, I had to stand on a box. I was a bit of a runt in those days, so my dad made a cube out of plywood and painted it white, and I stood on top of it. If I didn’t, I was so short my rope would hit the ground when I spun it.

We did rope tricks like Wedding Rings, the Merry-Go-Round, Ocean Waves, and Texas Skips. During the commercial break, the judges were talking about who they were going to award first place. Our family was kind of huddled together, and I remember hearing the judges say, “Let’s give it to those Idaho cowboys from Coeur d’Alene.” And they did. They awarded us first prize for the talent show that night. I don’t remember what the prize was, but the name “The Idaho Cowboys” stuck. From then on, we were billed as “The Idaho Cowboys, Buckshot and Smokie.”

By the time I was six or seven, Smokie and I joined the Rodeo Cowboys Association, now called the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA), and had started performing at local rodeos around the country. Most of these shows were little “pumpkin rollers” that didn’t amount to much, but they were a big deal to us.

A rodeo performance in Spanish Forks, Utah, in 1971. From left: Ace Brannaman, Buck, bullfighter Tim Oyler, and Smokie.

My dad changed jobs quite a bit during this period, but most of the time he was working for himself in his saddle and boot repair shop. He worked around our roping career so he could haul us to rodeos. The money that we made all went into his pocket, so the trick roping was kind of his job, too, or so he looked at it.

Our mom was quite a seamstress. She’d buy material and make us flashy outfits like the singing cowboys used to wear on stage and in the movies. I still have some of them. Other than a couple of pictures and some really nice memories, they’re all I’ve got left of her. I wish I could have known her as an adult.

In 1969, Smokie and I performed at our first indoor rodeo, a big one called the Diamond Spur Rodeo in Spokane, Washington. We had done trick roping at quite a few amateur rodeos, and we were getting to where we were fairly well known in northern Idaho and eastern Washington, but we were just starting our professional careers elsewhere.

It was a Thursday, the opening night of the rodeo. I looked into the coliseum from the back gate and saw eight thousand people in the grandstands. It was the biggest crowd I had ever seen, and I was very nervous. There were horses of every color moving in and out—it seemed like chaos at the time—but everyone knew where they were going. For a little kid who had barely been outside the Idaho panhandle, it was an amazing spectacle.

The rodeo clowns were getting their jalopy-car act prepared near one gate, while the barrel racers were blasting up and back along one of the handling chutes. Then the announcer started giving his introductions for the evening performance, and through all the confusion I heard, “Ladies and Gentlemen, The Idaho Cowboys!”

The plan was that Smokie and I would gallop into the arena on our pintos, make a full circle, do a sliding stop in the center, and then stand up on our horses and begin spinning ropes. When we made our grand entry, I had no time to be scared. Smokie took off first. He tipped his hat and made his circle, and I was right behind him. I got about a quarter of the way around when my mare Ladybird decided she was going to save us a lot of time. Evidently she thought

making a full lap was pointless. She cut hard to her left and took me right out toward the center of the arena.