Faraway Horses (8 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

Buck on an international tour with the Friendship Force, spinning ropes for the local media in Newcastle, England.

My stint with the Friendship Force convinced me there was no reason I couldn’t make a good living doing rope tricks. I put what money I had together and took off for Denver and the big stock show held there every year.

The rodeo producers held a convention at the Brown Palace Hotel, where you went to get your jobs for the year. You promoted yourself by renting a booth and putting up a little display. Because my dad had always handled that part of the business, I knew very little about it. I hadn’t realized

there was a lot more needed than just being a good trick roper, so I wasn’t prepared at all.

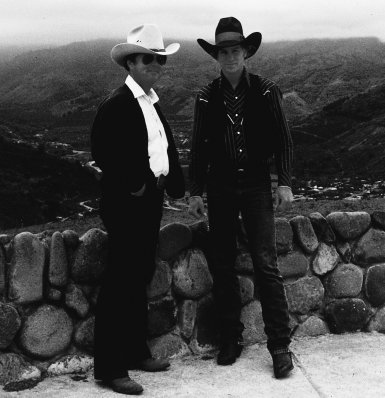

Buck in Costa Rica with Mike Thomas, manager of the Madison River Cattle Company.

I spent most of what little money I had on a hotel room, and most of the rest for booth space, but I had nothing to put on the booth. A friend named Doug Deter helped me take some pictures out in the snow, and we put them on a poster board and tried to make some sort of a display. In addition,

I had some pictures in a photo album that showed some of my rope tricks, but on the whole it was a pretty sorry presentation.

I sat for three days and watched the rodeo producers walk by and stop at the other booths. Every producer had a little contract book, and I saw contracts being signed right and left. It seemed as if everybody was signing contracts, but by the third and last day of the convention, I hadn’t signed a single one. All the money I had saved up was gone, and I had no prospects. Although I was really a good trick roper, probably the best one there, no one knew.

Every day at 4:00

P.M.

was happy hour, when the convention committee members passed out free booze and everybody joked, laughed, and told stories. During happy hour on the last day, a very influential rodeo producer passed my booth.

Forcing myself to summon up the courage to speak with him, I stopped him and asked, “Sir, would you take a moment and look at my album in case you would ever want someone to do some rope tricks at one of your rodeos?”

He just looked at me and said, “Son, I’ve looked at so goddamn many pictures today, I don’t care if I look at another one.”

“Well, I’m committed now,” I told myself, then practically begged him to look at my pictures.

The producer didn’t sit down. Instead, he just flopped my album open on a table in somebody else’s booth and started flipping through the pages. He never looked at a

single one. He was laughing, joking, and greeting people across the room.

Buck practicing his roping around the time he was looking for rodeo work.

When he spilled his drink in the middle of my book, I took it away, slammed it shut, and said, “Thanks for your time.”

He just glanced at me. He didn’t say anything. What happened to me meant nothing to him. As you can imagine, happy hour wasn’t so happy for me. I went upstairs to my room, threw down my photo album, lay on my bed, and cried. Nobody cared.

I went back to ranching and really thought about quitting rope tricks. I had a good cowboying job, but I had no roping jobs and no prospects.

Later on that summer a rodeo contractor named Roy Hunnicut out in Colorado called me. He said, “Son, I’d like

to hire you to do some rope tricks for me in a few rodeos. A guy who was trick riding for me broke his leg. You’re the only one who’s not working. I want to give you a try at one in Rock Springs, Wyoming. If I like what you’re doing, I’ll give you the rest of my rodeos.”

The manager of the ranch where I was working was happy for me. “As long as you come back in time to get the colts ready for the fall sale,” he told me, “you go ahead and hit some of these rodeos.”

I drove all night to get to Rock Springs for the Red Desert Roundup Rodeo. I didn’t have much of a fancy truck, trailer, or horses. In fact, my old horse trailer featured a variety of spreading rust motifs by way of decoration. But I had some damn good rope tricks.

There were five or six thousand people in the audience. I did my best stuff, and it brought the house down. I got a standing ovation.

Since I hadn’t been sure whether Hunnicut would take me on for the rest of the season, I had left some of my stuff back in Montana. A friend named Bob Donaldson had asked me to give him a ride to Douglas, Wyoming, on my way back to pick up my things. Bob, who was working the high school rodeo finals there, offered to introduce me to the producer of that event. He said, “I think he’d really like to talk to you. He’s heard that your rope tricks are really good, and he really wants to give you a job. He could be a great connection for you.” I knew who the man was but I didn’t say a word.

When we got to Douglas early the next morning, this big-time producer was sitting around and drinking coffee with a

bunch of his cronies. Bob introduced me to him, but the rodeo producer didn’t recognize me. Of course he didn’t; he had been too full of himself that afternoon in Denver.

He said, “Well, I’m so-and-so, and I’ve got a lot of big shows, some of the biggest rodeos in the business, and I heard you’re really a hell of a performer. I’d like to give you some work, son.”

I replied, “Well, sir, I know you don’t remember me, but I certainly remember you. And it’s not that I don’t need the work, because I do. But working for you and going to those big rodeos wouldn’t mean near as much to me as telling you to kiss my ass. You still don’t remember me, and it doesn’t matter. But because of what you did to me at one of the lowest points of my life, I’ll never forget you. It’s people like you who are going to make me successful one day.”

Thanks to Roy Hunnicutt, I had plenty of success with my rope tricks, if you want to call it that. I was good at them, but it was kind of a dead-end deal. I was lucky to make $200 a performance, and by the time I’d paid my expenses, I was making less money than cowboying for $450 a month. Besides, I had a lot better time on the ranch than I did on the rodeo circuit—the loneliness of being on the road got to me, too, so after a few years, I went home to the ranch.

However, I’ve never forgotten the impression that “big-time” rodeo producer made on me. He wouldn’t give me his time because he didn’t figure I could do anything for him. He didn’t respect me as a person. That was a good lesson I’ve never forgotten.

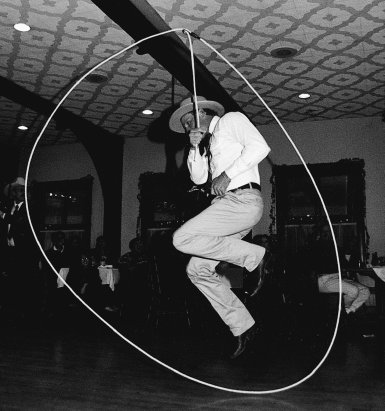

Always up for a good cause, Buck does the Texas Skip at a benefit for the Sheridan Inn in Sheridan, Wyoming.

Now that I’ve reached the point where I have a certain amount of influence, I try real hard to take time out for people who may expect not to be noticed. If somebody writes me a letter or comes up and talks to me, I appreciate the courage the effort may have taken, and I try to give them my time. I try to learn their names.

It hasn’t been that long since I was in their position.

Learning to Listen

B

Y THE EARLY

1980

S

I had spent a lot of time with a lot of great horsemen. I was learning how little I knew about horses and how much more I needed to learn. I’d ride horses all day and then consider the day’s work while trying to sleep. I was constantly confounded, but eventually solutions would present themselves.

When I moved to Gallatin Gateway, Montana, I didn’t have any customers, but I had a horse or two of my own. I rented an indoor arena up Gallatin Canyon, at the Spanish Creek Ranch, and then took an apartment in the old Gallatin Gateway Inn.

The inn, which has since been renovated, is a beautiful turn-of-the-century hotel now, but in those days it was pretty run-down. The owner had been trying to remodel the place, and like a lot of owners before him, he had run out of money. Of the two apartments next to the downstairs

bar, I took the one with the broken windows because it was cheaper. It had a few carpet remnants on the floor, but it wasn’t much beyond that. The bunkhouse at Madison River seemed like the Taj Mahal by comparison. The bar still had a liquor license, so a few of the local winos would come in and have a drink or two in the evenings. Otherwise, the building was vacant.

After renting the apartment and the arena, I was down to a roll of dimes, which I used to start making phone calls from the pay phone outside the bar. I called everybody I knew with a horse who might know somebody who had colts I could ride. I scored a couple, but I wasn’t going to get paid until I’d ridden them and their owners were satisfied. That meant I was at least a month away from getting a paycheck.

All I had in my cupboard were a box of Krusteaz Pancake Mix and a big tub of margarine. That’s pretty much what I lived on for a few weeks. And even after I was paid, there were still bills to be paid, so I continued to live on Krusteaz Pancake Mix and canned chili.

The arena at Spanish Creek was about five miles up the canyon from the inn. Times were so tough I didn’t even have the money to put gas in my truck, so getting there and back meant riding a horse along the side of a fairly busy highway. In the evenings I’d trot down in the dark with the logging trucks that roared by on their way out of the mountains. I’d hobble my horse in the tall grass behind the inn and let him graze there all night. The next morning I’d get up before

daylight and trot him back up to the arena. Of course, the inn’s owners would have run me off if they had found out I had a horse in the backyard, but they never found out.

It was another month before I was able to put a little gas in my truck and drive back and forth.

Spanish Creek was right next door to The Flying D. I got paid to ride some of their colts, which is how I met my “partner in crime,” Jeff Griffith. Jeff’s dad, Bud, was the manager of The Flying D. Jeff was still living at home with his folks, and we spent quite a bit of time at Spanish Creek riding horses. During the week I helped him with some of his dad’s colts, and we cowboyed together. On the weekends we’d head out to the local cowboy bars. We spent most of our money on girls and booze, and the rest of it we wasted.

In those days I was charging $125 a month to train a colt. At that rate, it worked out to close to a dollar a ride. I was still trying to get a business of my own going, and I was still practicing my rope tricks to see if I could score some TV commercials. I didn’t have an agent at the time, but I was acquainted with a commercial director from Bozeman named Marcus Stevens. Marcus and I met in Gallatin Gateway and got to be friends, and he gave me quite a bit of work over the years. I also got calls from a few producers who learned about my rope tricks through the PRCA. I made commercials for, among others, Visa, Best Western Hotels, and Busch beer. The commercials took a while in coming, but once they started, they helped pay the bills.

I lived at the Gallatin Gateway Inn for a year or so; then in 1983 I moved into a trailer house on The Flying D. It wasn’t much better than the room at the inn, but it was closer to my horses and saved me the drive to the arena.

After I had moved out of Forrest and Betsy’s house, their son-in-law Roland, who was married to their daughter Elaine, took over the ranch. Forrest retired to Arizona, but Betsy didn’t—she couldn’t leave her kids and the ranch. Roland, Elaine, and Betsy stayed on the ranch many years.

Forrest died during the winter of 1984. I didn’t get to go to the funeral. It was the dead of winter, and I couldn’t get away; luckily I had seen him about two weeks before. I had taken a trip to Mexico with my foster brother Stuart Shirley and his wife, Annie, and we stopped over and saw Forrest for a couple of days. Forrest had just come back from the VA hospital with a clean bill of health. We had a great visit, and it never crossed anyone’s mind that he wasn’t going to be around much longer.

It was a real shock when Stuart called me in the middle of the night to say that Forrest had passed away. The cause was an aneurysm in his lungs. I can’t describe how bad I felt. At the same time, I felt guilty. My dad was still alive at the time, and I found myself thinking I would have gladly traded my dad’s life for Forrest’s. I thought there must be something wrong about that, but I couldn’t help feeling that way because of everything Forrest had taught me.

Solutions to problems often come from knowing when to ask for help.

While I was riding colts for the public at Spanish Creek, I was having trouble with a roan horse. I’d been working for a while on getting him to turn around and on getting him balanced. By “balanced” I mean getting him so he’d move the same way in both directions. At that point he was pretty much the same on both sides, but it was sticky going either way.

It was early morning on a fine summer day. As I looked over the top rail of the round pen, the only sound was that of my horse catching his breath. Through the steady rhythm, I realized how desperate I was to solve the problem. Nothing seemed to work. I did everything I thought was correct; for example, I tried leading with my right rein and supporting with my left rein against the base of his neck and putting my left heel against his side. Still, I didn’t get any response. I couldn’t get the horse to put out any effort. If I asked him to put any effort into turning to work a cow, he wouldn’t go any faster. It was as if he was going in slow motion. The more I kicked and the more I pulled, the worse it got.

I was frustrated to the point of tears. I couldn’t seem to make any headway.

Now, Montana may be short on population, but it fills the void with a fine lot of colloquialisms. “If you don’t get it, you’d better be barking at the hole,” is one of them. It means “keep trying.”

I knew I needed some guidance, and since Ray Hunt was off doing a clinic and I had no way of getting ahold of him, I figured it was worth a shot to call Bill Dorrance.

Bill was Tom Dorrance’s brother. He and I hadn’t met yet, but for years Mike Beck, a good friend from the Madison River days, had been telling me about the man’s horsemanship. They had spent quite a bit of time together on Bill’s ranch near Salinas, California, and according to Mike, Bill’s skill with a bridle horse and the way he handled a rope were legendary. If I was ever to be a Jedi, I needed an Obi-Wan, so I took a deep breath and called him.

“Bill, you don’t know who I am,” I stammered, “but I need some help with my horse. Mike Beck told me what a great horseman you are, and I’ve admired the things you’ve shown him. I hope you can help.”

He didn’t say anything, so I went on. “My horse turns around pretty good, but I can’t seem to get him to put any effort into it.” I told him all the things I had done with the horse, how frustrated I had become, and how worried I was that I was pushing this nice little horse harder than he deserved.

When Bill finally spoke, he acted as if he’d never heard a word I said. He started talking about the hindquarters. “You know, Buck, if you can move the hindquarters right or left, you can get his body arranged to where he can do some things that you didn’t think he could do.”

I just sat there and thought, How sad. Poor Bill has gotten so much age on him that he didn’t hear what I asked him. I suppose I was hoping that Bill would tell me just to take the tail end of my McCarty rein and whack the horse

across the shoulder, or maybe to turn my toe out and use my spur to move his front quarters. I had no idea why he was talking about moving the hindquarters right or left.

I asked him again, “How can I get my horse to turn around a little sharper so I can get him to work a cow a little better?”

Again he said, “You know, if a fellow can get a horse reaching backward a little bit, it will help him. It’s amazing how much the hindquarters have to do with all the things you do with a horse to get a job done.”

There he goes again, I told myself, he’s talking about the hindquarters and avoiding my problem. It was as if he hadn’t heard a word I said.

I asked Bill one more time what I should do about my problem with the front quarters because I was sure that’s where the problem was. Again we ended up talking about the hindquarters. I decided that no matter how I asked him about the specifics of my problem, he wasn’t able to understand me.

I decided to give up on it for that day, and we finished our conversation talking about horses we had ridden and folks we both knew. I thought we’d just had a nice conversation. At least I’d had a chance to talk to the legendary Bill Dorrance, which really meant a lot to me. So I left the other part alone.

The next day I went down to the barn to see the horse. I stood there looking into his eyes as he ate. I felt sorry for him, and I felt sorry for myself. I was feeling down on myself

about the way I had been with the horse. I had been riding him really hard for a few days just to get this one fast turn out of him, and it wasn’t fair of me. So I decided I would just take a ride and not fight with him. That day we would simply enjoy each other. We’d take a ride out through the hills, and I wouldn’t ask him to do anything difficult or anything I didn’t think we could do.

It was the fall of the year, and the leaves had started turning up in the aspens. I sensed the urgencies that seem to effect the change of seasons, and I got to thinking then about other kinds of changes, too. Perhaps this horse thing was something I wasn’t going to be able to do very well. Maybe I’d rekindle my trick-roping career because I’d been pretty successful at that.

All throughout that ride I just tried to leave the horse alone, but on the way back to the barn, I stopped. The message Bill had given me kept creeping into my brain. I decided to see whether, if I could stop the horse with one rein and untrack his hindquarters a little bit, I just might get him to step over behind.

When I tried to do what Bill had so subtly suggested, my rein felt as if it was tied off to a big rock or the back of a truck going the other way. I couldn’t get the horse to budge in the direction I was asking him to go. He hardly had any bend in him at all. I couldn’t get him to step over with his hindquarters (move his hindquarters right or left), and that kind of surprised me.

And so I worked on getting him to step over. As down on myself as I was that day, I figured I could at least accomplish that much. At least I could get him to bend.

After much leg-pressure urging, I got the horse to untrack his hindquarters a little bit, to step over behind and bend more through his loin and rib cage. He had a little more “give” on the end of the rein, and was a little more supple in his movements. He felt lighter in my hands.

After having accomplished that little bit, I tried to keep my promise to the horse not to bother or pick on him, so I started back to the barn with a loose rein. But something continued to eat at me. I asked the horse to turn around over his hindquarters. And to my great surprise, he spun so fast that he reminded me of Ayatollah’s high-velocity turns, yet he was relaxed.

I did this once, and then, remembering the other roan horse with a sagebrush stuck in his butt, I reminded myself, “You know, you better leave that horse alone because it’s not going to get any better than this, that’s for sure. The way you’ve been riding the last few days, you’ll probably wreck it in the next few minutes.” So I walked a brisk walk back to the barn and unsaddled the horse before I destroyed what I’d been trying to get.

While I was putting my gear away, I reviewed what had happened. There was no way I was going to get that horse to turn around any faster without freeing up his hind end. Somewhere along the line I’d lost the hindquarters. I’d had

control of them at one point, but I got so busy trying to be a “horse trainer”—and I say that with much chagrin—I’d lost the basics that prepares any horse in the first place.

I also reviewed my own attitude. “I’ll be damned,” I told myself, “Bill tried to tell me which end of the horse needed work, but I couldn’t hear it.”

I called Bill again a few days later. I really wanted to tell him about my progress with the horse. We chatted about this and that, and after a few minutes, he asked, “How did things work out with that roan horse that you were telling me about?”

I said, “Well, Bill, I found that those hindquarters were not shaped up very well. His hip was in the way, it wasn’t underneath him, and considering the way he was prepared, he was turning about as fast as he possibly could. I got him all shaped up now, and he’s happy to turn for me. We’re getting along well again.”

I’ve often said that if you took away the fact that Bill was a great hand with a rope and a gifted horseman, what you’d have left is a really fine human being. Considering I hadn’t really been listening to him the first time we talked, he could have replied in any number of ways. He might have said, “Well, I told you so,” or, “If you had listened to me in the first place.”

But Bill didn’t. He didn’t rub it in. It wasn’t about being right or wrong, and he was a gentleman about it. He just said, “Well, that’s real good that worked out for you, Buck. I’m

glad that things are starting to shape up between you and that horse.” That was characteristic of Bill Dorrance’s approach. He had the answer, but he never tried to ram it down my throat. That hadn’t been my way: I thought I had the answer, and I had been trying to ram it down the horse’s throat.