Faraway Horses (11 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

I’ll never be able to repay Bif for what he’s taught me about working with horses. He represents a lot of horses and people, too, who simply got a bad deal at the start. He proves to me that you don’t give up, and that even if you’re going through something that makes you think your life is over, you can still have a future.

I travel all over the country and get an opportunity to see lots of different people, and lots of different lifestyles and ways of doing things. All in all, I’m actually pretty optimistic about the human condition. I think of all the people who are unfortunate, who don’t have good jobs, or who are on welfare. Granted, some of these people are just lazy, and even though they could work, they won’t. Maybe they weren’t raised right, or maybe they weren’t influenced by the right set of circumstances or the right person. But there are other people who aren’t lazy and who do want good jobs, and for them, welfare can help. Some of these people prevail despite a rough start and end up with successful lives. There are Bifs all over.

I’m often asked about a welfare program for wild horses called Adopt-a-Horse. It’s been quite a hot issue in the

West, where a lot of people on both sides are trying to do the right thing.

Nobody wants to see wild horses disappear from the western landscape. The activists who regard them as indigenous and want to protect them all certainly don’t. Neither do most ranchers, some of whom consider the horses to be simply feral. Although the media paints the rancher as the great Satan because he’s in favor of culling the wild herds, the rancher is not a bad person. His concern is overgrazing. He wants all animals to have enough to eat, including his cows. Most real ranchers love horses, and they love the freedom that the wild horse represents. They just don’t want to see the population become so large that the animals will starve to death.

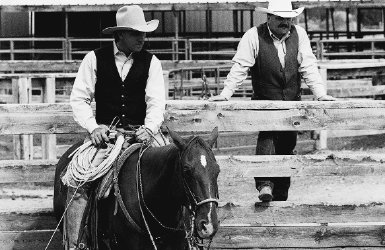

Buck shows how calmly a young sale horse responds to his “big loop” demonstration at the Dead Horse Ranch Sale in New Mexico.

In their infinite wisdom and in an attempt to resolve the issue, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) created the Adopt-a-Horse program. Government officials started rounding up wild horses and holding them in concentration camp–like environments called feedlots, where they were made available for adoption by anyone who wanted a horse.

The BLM thought this would satisfy both the ranchers who wanted a solution to the problem of overpopulation and overgrazing and the activists, mainly people from towns, who wanted to prevent the horses from going to slaughter.

Although the BLM was trying to do the right thing, Adopt-a-Horse didn’t work. Allowing people without any qualifications to own a horse, much less a wild one, put lives in danger. That’s an injustice to both the horse and his owner. If the horse hurts an owner, the animal gets the blame.

The BLM also created a program in which prisoners are given the opportunity to work with captive wild horses. They gentle them and get them to the point where they are ridable. This is an excellent idea. People who want to own a horse, especially those who have no experience with horses, are a whole lot safer. The horses don’t end up in a can of dog

food, and the prisoners learn skills that can benefit them when they’re released. If nothing else, they’re doing something they can feel good about.

I have hope for these wild horses. They are a part of the American West that most people want to see survive. Most of you who are reading this book feel a deep-down ancient bond, a connection between yourself and horses.

Down the Road

T

HE FIRST CLINIC I EVER DID

was in 1983 in Four Corners, Montana, at an indoor arena owned by Barbara Parkening, the wife of Christopher Parkening, the famous classical guitarist. She had a little group of four or five lady friends who all rode together. I’d started a couple of colts for Barbara’s brother-in-law, Perry, and he had been trying to get me to give them a horsemanship class.

As this point in my life I was really shy about talking to people in public. I didn’t mind performing—my rope-tricks career proved that—but I didn’t feel comfortable speaking to groups. Even when I was riding colts, I didn’t like people coming around and watching me. They made me nervous. I didn’t want the social interaction because it scared me. All I wanted was to be left alone with a pen full of horses.

Perry kept encouraging me, telling me that I had a lot to offer and that I’d do fine in a public situation. I had gotten

to know and trust him, so finally I offered him a deal. “All right,” I said, “I need maybe a dozen people to make it work. If you get everything lined up, if you make all the arrangements, collect all the money and rent the indoor arena, I’ll do the clinic.” I figured that if I gave Perry all of the responsibility and I didn’t take any interest at all in the deal, he’d just forget about it.

That’s not what happened. Perry came back a week later with the news that he had the people signed up, he’d collected the money, and he’d rented the arena I wanted.

Since Perry had done what I’d asked him to do, I had to be good to my word. I showed up and put on a clinic, but to be honest, I don’t know if anybody learned anything. I did what many people do when they first get in the teaching business: I tried to sound as much like the teachers I’d had as I could, parroting things that I’d heard over the years.

That’s because I had more confidence in my teachers than I had in myself. I couldn’t consider myself an authority, someone with anything to offer, when I’d never done something like this before. I was so unsure of myself speaking to a group of people, let alone teaching them, that I really don’t know if they learned anything.

When the clinic was over, a little gray Arab was still in his trailer. One of the students had loaded him because she’d wanted to ride him, but she couldn’t get him to back out.

I often tell people that if they can’t get a horse to back up on the end of a lead rope in the open, they may have a little difficulty getting him to back out of a trailer. A lot of times

a horse would rather flip over than step down into the unknown.

One of Buck’s greatest pleasures is to put on clinics with the friends who were there for him when he started his career. Here Buck engages a crowd in Billings, Montana, at a clinic sponsored by his friend and saddler, Chas Weldon (standing at right).

The horse was terrified to come out. I did the best I could to get him to step six inches back, then step a foot or two forward and another foot back. This was to help him gain some confidence moving forward and back in the trailer before he stepped down.

It wasn’t easy, but I finally got him out of the trailer. He didn’t hurt himself, but he could have. Then I explained to the woman the mistake she had made in the first place. Rather than loading her horse all the way into the trailer before she was sure she could get him out, she should have had

him step carefully into the trailer with his front feet, then had him back up while his hind feet were still on the ground. Doing this procedure a few times would have given him the confidence he needed to back out once he was loaded.

If you ever make the mistake of loading a horse into a trailer without having taught him to back up, the best thing to do is park your truck and trailer inside a corral, leave the back door of the trailer open, shut the corral gate, and go to bed. During the night, the horse will get it worked out. He’ll come out. That’s the lowest-risk way of getting him out of the trailer.

Or, if you’ve got just one horse loaded in a two-horse trailer, you could remove the dividers. Even though it’s a pretty cramped space, you can often encourage the horse to turn around.

Many people consider loading horses into a trailer as something akin to having open-heart surgery. They know they need to do it, but they’ll do everything in their power to avoid it. That’s because they don’t understand what loading is really all about. It’s really quite simple, though: if a horse leads well, if he walks with you wherever you wish to go, he’ll load well. It’s an act of trust between two beings.

At a clinic in California a few years ago, a lady hired me to do a trailer-loading demonstration with her horse. A couple of handlers walked him down to the arena where I was waiting. Then someone drove her trailer up. A few

minutes later, the owner herself showed up driving a Rolls-Royce. She stepped out of it and said, “Mr. Brannaman, I’m the owner of this horse, and I’m the one paying you to trailer-load him. I understand your fee is one hundred dollars. If you’re able to load him without too much trouble, I want to make sure I get a discount.”

No horse is a problem horse; there are only problem people. Of the more than ten thousand horses Buck has started in his clinic career, he has never failed a horse. Here he starts a big warm-blood in Malibu, California.

The hackles on the back of my neck raised a bit. Here the woman drives up in a two-hundred-thousand-dollar car, and she’s worried about not getting her hundred dollars’ worth (if the stories I’d heard about her own trailer-loading expertise were true, she’d never find a vet to stitch her horse up for any less than that).

I said, “Ma’am, if you don’t feel like you got your money’s worth by the time I’m done, then you don’t owe me anything.”

I started the horse on the end of the halter rope, shaking the rope just enough to get the horse to move his feet back. I was being as subtle as I possibly could, trying to offer him a good deal. When I didn’t get the movement I wanted, I got a little more active with the rope until the discomfort of the swing caused him to back up. The effect of the rope wasn’t a lot different from a big horsefly buzzing around his head. The rope made him drop his head and back up, the same way a horsefly would.

Once I laid the foundation of getting the horse to move his feet, I could back him just about anywhere I wanted him to go. After just a little while, he was backing very nicely on the end of a sixty-foot rope. I then fed out the rope’s coils and backed him up the ramp and into the trailer. His hind end was all the way in the manger and his head hung out the back door. I even got him to where he would start beside the driver’s window of the pickup, walk down alongside the truck and trailer, turn the corner, and back up the ramp on his own.

That’s when I put the halter back on the horse and handed him to his owner. “There you go, ma’am,” I told her. “I’ve finished with your horse.”

Her eyes bugged out so far you could have knocked them off with a stick. “You never loaded my horse.”

“Oh, yes I did, ma’am,” I replied and turned around to the crowd. “Did I not load this lady’s horse?” Everyone confirmed that I sure had.

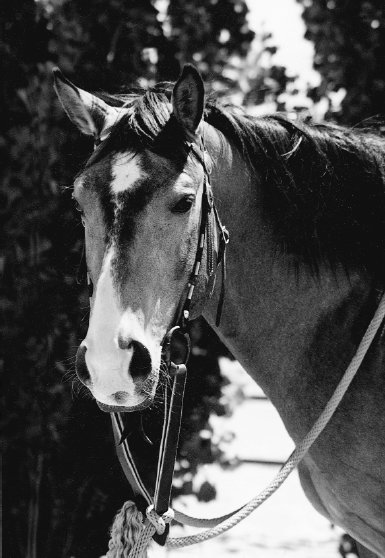

Buck’s little buckskin gelding, Cinch, has traveled with Buck over the years and become almost as well known as Buck himself. Cinch is retired today on Buck’s ranch in Sheridan.

She said, “Well, yes, you loaded him, but you loaded him backward.”

I put a puzzled look on my face. “Well, ma’am, you didn’t say which way you were looking for me to load him, so I don’t know how I was supposed to know.” With that, I reached into my pocket and gave her back her check. “You have a good trip home, ma’am. I hope everything goes fine for you and your horse.”

The last thing I saw at the end of the day was the horse on his way out of the arena, his butt in the manger and his head hanging out the back of the trailer. As he went out the gate, he whinnied at me as if to say, “Well, thanks. It wasn’t really what I expected, but I’m in anyway.”

The last I heard, that lady was successfully loading her horse on her own. She was still loading him backward, but she was loading him, nevertheless.

It’s kind of like the old saying: Be careful what you ask for; you just may get it.

Loading wouldn’t be a problem if leading weren’t a problem. I wish I had a dime for every horse I see either dragging his owner along at the end of a lead rope or else being dragged. Or make a right turn by being turned to the left three times. You’d think the person would be embarrassed to death, but he’s not. I know I would be.

Problems with leading happen because the basic groundwork is lacking. A horse that has learned to hook on to a human and to free up his feet will follow the person calmly and willingly.

One thing, though: People often lead from the wrong place. They walk either directly in front of the horse or back at the hip. Both spots are blind spots where the horse just can’t see you, so no wonder he’ll run over the top of you or swing into you and knock you flat. Try to be enough to the side and ahead so he can see you. You should be able to make a right turn and not run over the horse to get there.

And speaking of embarrassment, I can’t imagine why people who have to stand on a box to get a halter or bridle on their horse’s head aren’t mortified to let others see them do it. Any horse that can reach down to graze—and that would be every horse—should be able to lower his head so even the shortest person can put on a halter or bridle.

That’s why when I start working with young horses or help older troubled ones, I always rub them along on the neck and around the ears. Comforting and supportive touching around the head means a great deal to them. They’ll welcome it and put their heads down for more, even when you have a halter or bridle in your hand.

I also make sure that I don’t slam a bit into their mouths. That’s a quick way to make a horse head shy.

Okay, one more point in this area: A horse that walks off while the rider is stepping on is a reflection of the owner’s weak horsemanship. It puts the rider in a precarious position, and it shows that the rider has lost control. All my horses stand while I mount, and they don’t move off unless and until I ask, even if they see other horses moving around.

My horses listen to their rider, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Nor do my horses leave me when I turn them out in a paddock or pasture. They stand quietly while I remove their halters, and they continue to stand while I leave them. That is, I walk away from them and not the other way around. That way, there’s never any spinning around and kicking out, so nobody gets hurt.

Early in my teaching career, I gave a summertime clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was 117 degrees, and the dust in the arena was like flour. Nowadays I wouldn’t put horses or people through that torture, but we all suffered along. So did the arena crew, who did the best they could to keep the footing watered.

The horsemanship class had about forty people trotting around on their horses in the dust. The sun was blazing, and about halfway through the class, I suggested that everyone take a break for a few minutes.