Faraway Horses (15 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

I loped up, swung my mallet, and when I hit the ball, the sound was the same as a perfectly hit baseball. What’s more, the ball soared about 125 yards through the air. Cool, I thought, but I also thought, What blind luck! I hope I don’t

have to hit another one … maybe I’ll just let Brett go ahead and hit the rest.

But Brett hit a ball, then looked over at me, backed his horse up, and sort of pointed to the balls as an invitation to go again.

Off we went. We went through all the polo shots: neck shots and tail shots, forehands and backhands, from the near side and the off side. I don’t know how it happened, I still can’t explain it, but every shot I took, I hit the ball like Willie Mays hit baseballs. I never missed a shot. It worked out great, but I still couldn’t wait for the whole thing to be over with.

That was a lucky day in more ways than one. I met some wonderful people, including Prince Charles. Considering my humble beginnings, I never imagined that one day I’d get to shake hands with a prince, and I was grateful for the opportunity. I also met George Plimpton, who’s made a career of being “someone else” and then writing a book about it. So I felt a kindred spirit, since I was impersonating a polo player.

I don’t know if I’ll ever go back to Palm Beach for another polo season, but I met some good folks that winter, and I learned a lot about polo ponies. The experience made me a better hand with horses, and I know it made me a better teacher in terms of being a little more well rounded.

On the downside, I did see an awful lot of troubled horses. But that was one reason I was there: to help fix some

of the horses. I saw a lot that wouldn’t have had so many problems if they’d had better handling. And as for those masters with a polo mallet, some could handle a polo ball like nothing you’ve ever seen, but if you hanged them for being horsemen, you’d be hanging innocent men.

That’s true of a lot of other horse events. The horse kind of takes a backseat to the event itself. The horse becomes the vehicle. So maybe that’s the reason there’ll always be somewhere for me to go. Those horses need someone on their side.

As long as I live and can swing a leg over, the horse has a friend who’ll fight for him.

Farther Along the Road

W

E HAD TAKEN TWO TRUCKS

full of horses down to Florida that winter, and we laid over in Baton Rouge for a few days’ rest. While we were there, someone arranged for me to do a free demonstration to drum up interest in clinics in that part of the country.

Angel Benton, a friend from Colorado, asked a local trainer who was in the gaited horse business to find a horse for me to work with. I guess the fellow was insecure about a stranger from out of town coming in to show how to work with horses. He must have thought, This’ll be good, and he lined up a horse.

He also didn’t keep it a secret. “Hell of a crowd, for people who don’t know me,” I said to myself when I showed up.

A gray horse waited in the round corral. Before I went in, a Cajun man took me aside said, “I don’t know you, Mr. Buck, but you watch that sum-bitch because I know him.” No one else volunteered a thing.

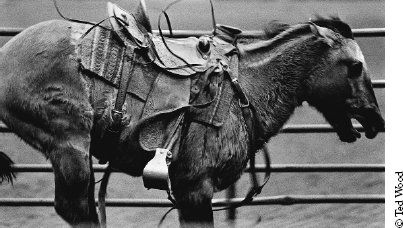

A never-before-saddled colt at the Denver Stock Show, bucking wildly after Buck saddles him. Buck allows the horse to buck and run, getting used to the saddle.

I asked what had been done with the horse. When I do that, I’m not fishing for information about the horse. I’m interested in finding out about the person or people who’ve been working with the animal. That’s because a horse’s behavior reveals as much about a person as it does about the horse. Then, too, if my well-being depended on the accuracy in reporting a horse’s background, whether intentionally or inadvertently, I’d have been dead a long time ago.

I was told the horse’s owners had tried to start him a couple of times. He bucked off lots of people, and once, when he ended up with the saddle under his belly, he went through a few fences. That didn’t surprise me. It happens all the time—it’s as common as morning coffee.

Buck approaches the same colt in a gentle and friendly way after it finishes bucking.

As I started moving the horse around the corral, I asked myself, “This is supposed to be a two-hour demonstration?” Although I knew the fellow who found the horse thought it would take only a few minutes for the horse to eliminate me, I also knew I’d have the horse ridden in no time. Then what the heck was I going to do for the two hours?

The horse bucked pretty hard when the girth was tightened, but that was the extent of the excitement. So, to fill the rest of the two hours, I came up with every trick I could think of. I led the horse by one ear, by the lip, by his tongue. I even led him by his feet.

These things are based on the unspoken but very evident draw or appeal to which another creature responds. Please

note that I say “creature” because the connection works for us humans, too. For example, you can ask another person to dance, but even though you say the right words, the way you say them may not attract him or her. On the other hand, the right “feel” can be sensed across a room without a word being spoken—think of the lyrics to “Some Enchanted Evening.” The other person may have seen you and then made up his or her mind to dance the whole night with you even before you said a word.

And how do you know? You feel it. “Feel” is the spiritual part of a person’s being. There are a thousand explanations for “feel,” and they’re all correct. Horses have it, and they use it all the time. You can’t conceal anything from a horse: he’ll respond to what’s inside you—or he won’t respond at all.

I ended up the demonstration by riding the gray horse all around and then swinging a rope around him. When I had finished, I stopped the horse, who stood there hip shot (meaning he was so relaxed, his hindquarters weight rested on one hip).

I looked around at the crowd. “I know a lot of you came here to see me fail, the way lots of people go to an auto race to see bad driving, not good driving. And then there’s this boy here who lined up the horse for me.” I called him a boy because he hadn’t earned the right to be called a man. “The sad thing is he didn’t know or care what would happen if I, a stranger to him, got hurt. Or worse. I might have a family to feed or a mother to support. All to try and prove a point that seemed important to him.”

I turned to the guy. “I want to know what makes you so different from me. I say different because I can’t imagine doing such a thing. Why did you do it to someone who

might

be a wonderful person, someone you might have liked knowing if only you got to know him? Just what is it that makes you so different?”

Of course the guy denied knowing anything about the horse—he was just getting me a horse.

I wasn’t about to let the guy off so easy. “I’m not the only one here who knows you can’t talk your way out of this,” I said. “Now let me give you a piece of advice. You were sure this horse would eat my lunch. Well, you’re a long way from where I live. Don’t come out to my playground because we play a lot rougher out there. We have this sort of horse for breakfast. Heck, our kids have this sort for breakfast.”

Later, as I was set to leave, I noticed three Cajuns standing off to one side and looking at me. I smiled and said hello, but they turned away. The fellow who had given me the warning saw what was going on. “Mr. Buck,” he said, “those men don’t want you to think they didn’t appreciate what you did today, but they suspect you have the voodoo.”

When I replied that I had no mojo—I was just a cowboy from Montana—the man laughed. “Well, they’ll sure be happy to hear that!”

People want to know whether my approach works with other animals. It certainly does.

Hooking on with a dog is easier than with a horse. Dogs are predators, not prey. Dogs respond to food, while food training spoils a horse. It’s seldom successful in the long run. The key to hooking on with a horse is to provide comfort. Comfort means more to a herd animal than it does to a predator.

Dogs are much more trainable than cats are. Characterizing cats is a lot like a husband observing his wife or a wife her husband: cats are gratifying, interesting, perplexing, frustrating, loving … all of these things and more. You control the destiny of a relationship with a cat the same way you control it with a spouse: peaceful coexistence.

When I worked at a ranch near Harrison, Montana, a cat showed up on my porch one day. He had pinkeye, so I doctored him with the pinkeye medication we used on cattle. The cat stuck around, and I named him Kalamazoo, after a Hoyt Axton song that was popular that year. For the want of something to do, I tried to see how much I could get done with Kalamazoo. I got him so he’d lead with a string around his neck, sit down, and roll over. He’d jump in the back of the truck. He always came when called. And I accomplished all of that without using food as a reward. Kalamazoo just had the capacity and the interest to learn.

Eventually, the coyotes got him.

Much can be learned from the nobility of horses, and from how genuine and pure their thoughts are. There is no reason for a horse to look at you any differently from how

he would look at any other predator. But when he learns that the two of you can go together and that going with you is better than resisting and going in the opposite direction, a feeling of comfort settles in him. His frame of mind begins to change, and he begins to view you differently.

Sometimes you’ve done your groundwork and your horse is comfortable. You get on but you’re tight, or worried. In that case, your body language is doing everything it can to get you bucked off, but your horse may remain settled even though you aren’t doing much to help him. That’s what I mean when I talk about the horse filling in for you. And filling in can be accomplished only after helping the horse gain a large amount of confidence before you step on.

Filling in comes from the horse’s being comfortable and trusting, both of which come in turn from groundwork.

People often ask, “How much groundwork do I need to do?” The answer is, enough to keep your horse and yourself out of trouble; enough to keep yourself from getting bucked off and from getting yourself and your horse in a wreck.

In other words, the amount depends entirely on how much you have to offer the horse when you get on his back. If you’re an experienced rider and can go with the motion without clashing with the horse’s energy, the amount of groundwork is a lot less than if you haven’t ridden much. If you’re inexperienced, unsure, and fearful, you’ll need to do a lot more.

Do people expect too much too soon? Most certainly. And a lot of times the people who expect too much too soon are the ones who are afraid. They want the horse to

come through, to get over all the things that he’s doing that frighten them without their putting in the time to help him. They want him to become advanced as soon as possible—if not sooner.

“Always go back to the basics” is something Buck stresses. As with playing scales on the piano, allow the horse to warm up with you. Here Buck does a little reminder groundwork with Bif.

On the other hand, people who have realistic expectations and enjoy working with a horse, allowing him to come along at his own pace, are the people who are confident. These are the people who don’t work with horses to stroke their own egos. They feel comfortable with the horse because they’re comfortable with where they are now. And that helps them be comfortable with where they’re headed.

People talk about horses that are lazy. That may be their opinion, but a lot of times I know it’s something else. Having

been through hard times myself, I know what it’s like to be in a situation where you’re basically a captive. That’s where many of these so-called lazy horses are. They’re captives doing time. As a kid, I couldn’t go anywhere else physically, but mentally I didn’t have to stay. Often the only way I could survive a really stressful situation was to go somewhere else in my mind.

Many people survive just that way when they’re young, and I feel sure that horses do, too, a lot of the time. They can’t open a gate, hitch up the trailer, load themselves, start the truck, and drive off. Physically they’re captives, and they have no choice but to remain. Because of a stressful life, an unhappy life with a human, those horses have to go away somehow. They have to leave in order to survive.

When horses do go somewhere else, their response may be very aloof. Humans will think that they’re lazy or that they don’t care, that they lack desire. These horses do not lack desire. They have lots of desire, but their desires can’t be fulfilled because they’re living in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Therefore, I’ll tell people who ask me whether their horse is being dull or listless or lethargic that the horse may have had to go away mentally to preserve the one and only thing that means anything to him. That’s his state of mind, his well-being. It isn’t always the case, but I’ve seen it happen quite a bit.

I don’t know that there is such a thing as a bad horse, but some are certainly more difficult to work with than others.

It isn’t always the fault of the owner. Sometimes, the owner has the best of intentions but lacks the knowledge, the ability, or the means to work with a horse that is in trouble. Horses just want to survive, and it can be hard for them to fit into the world we have created for them.