Father of the Bride (4 page)

Read Father of the Bride Online

Authors: Edward Streeter

Tags: #Fiction, #Humorous, #Romance, #Romantic Comedy, #Family Life, #Thrillers, #Suspense

• • •

“Are you awake?” asked Mr. Banks. “Hey, Ellie.” Mrs. Banks stirred uneasily.

“Are you awake?”

“What’s the matter?” she asked, noncommitally, regarding him with one unfriendly eye.

“I’ve been thinking,” said Mr. Banks. “I’ve been thinking all night. I haven’t slept.”

“You were snoring when I woke up,” she said, without sympathy.

Mr. Banks ignored the remark. It was merely part of Mrs. Banks’ morning routine.

“I’ve been thinking about Buckley,” he said. “I’m worried. Good and worried. Do you realize, Ellie, that we know next to nothing about this boy? Just because his family has a big house and a couple of maids doesn’t mean anything. What do we know about

him?

”

He raised himself on his elbow. “Think it over a minute. One day Kay comes home and says, ‘This is Buckley. Isn’t he cute? I’m going to marry him.’ And we all make faces at him and dance around. But what do we

know

about him?”

Mr. Banks began to check off his points on his fingers. “Has he got any money? You don’t know. What’s he making? Nobody knows. Can he support her? We just don’t know a darn thing about the guy. He walks in the door and we hand him Kay and—”

“Darling,” interrupted Mrs. Banks, “we’ve been through all this before. Ask Buckley. Don’t ask me.”

“Don’t try to laugh it off.” Mr. Banks was working himself into one of his pre-breakfast frenzies.

“I’m

not going to support him. Not by a damn sight. I’m—”

Mrs. Banks interrupted again. “Listen, dear. I think you’re absolutely right. I’ve told you so every time you’ve brought this up. We should have found out about these things long ago. I don’t know why you haven’t. You’ve been going to have a talk with Buckley ever since Kay first told us. Sometimes I think you’re a little afraid of him.”

Mr. Banks snorted. “That’s a fine remark, I must say. I intend to have a talk with him, all right. We might just as well have it out.”

He sat on the edge of his bed radiating aggressiveness. Mrs. Banks thought he looked rather gray and tired.

By the time he reached home that evening he had decided not to make a direct approach. No use scaring the boy to death. Instead he told Kay that he wanted to have a little talk with Buckley about finances. You know—what he was earning and all that sort of thing. As a sop to liberalism he indicated that he thought Buckley was entitled to know something about

his

affairs.

Kay accepted this with irritating patience. She said O.K. if that was what he wanted. Buckley was big enough to take it.

She

knew what he was making and that should be all that was necessary,

but

if Pops wanted to go into all that old-fashioned rigamarole—O.K. She’d give Buckley the message.

Several nights later Buckley arrived for dinner carrying a bulging briefcase. Mr. Banks eyed it dubiously. What did the fellow think he was—a C.P.A.? On the other hand, if he had enough papers to fill that thing, the picture might not be as grim as he had feared. Rather decent of the boy to take it so seriously.

Mr. Banks had visualized a quiet, dignified conversation during which he would be seated in a large armchair and Buckley in a straight chair facing him. Instead he found himself sitting beside Buckley on the livingroom sofa making old-fashioneds.

He finished his quickly. Somehow he felt the need of fortification. After a while Ben and Tommy drifted off on their own affairs and a few minutes later Mrs. Banks and Kay disappeared in the direction of the kitchen. It was Delilah’s night out. Mr. Banks was glad of this. Buckley would see that they were a quiet, simple family, well able to take care of itself, but not equipped to assume extra burdens.

They were alone. The time had come. Mixing himself another old-fashioned, he plunged.

“I guess Kay has told you,” he said, “that I wanted to have a little financial chat with you.” He thought this rather a footless opening in view of the briefcase resting at Buckley’s feet.

Buckley continued to regard him like a family doctor.

“Yes, sir,” said Buckley, reaching for the briefcase.

Mr. Banks raised a delaying hand. “In the old days,” he continued, “fathers used to say to prospective sons-in-law, ‘Are you going to be able to support my daughter in the manner to which she’s accustomed?’ ” Unintentionally he gave a throaty laugh. Buckley did not even smile.

“I know what you kids are up against, though, and I’ve got modern ideas about these things.” He stopped himself from adding, “although I may not look it.”

Buckley nodded understandingly. He reminded Mr. Banks more and more of a family doctor paying a professional visit.

“What I mean is I know what you young people are up against. You all need help and I believe parents should give it as far as they are able.”

“Yes, sir,” agreed Buckley.

“What I was going on to say,” continued Mr. Banks hurriedly, “is that parents are also up against it these days.”

“They certainly are,” said Buckley.

“You know what I mean—with high taxes and high prices and one thing and another.”

Buckley nodded sympathetically.

“The long and the short of it is I think you’re just as entitled to know where I stand as I am to know about you.”

“Yes, sir,” said Buckley, reaching for his briefcase.

Mr. Banks hurried on. “So here’s what I propose. I’ll start out and tell you a little about my own setup. You and Kay ought to know just how much you can count on us for help in the pinches—and just how much you can’t. Then you can go into your financial picture. How about it, eh?”

Buckley continued to regard him gravely.

“What I mean is, we ought to know about each other,” added Mr. Banks.

“Yes, sir,” said Buckley.

Mr. Banks took a thoughtful drink. “I’ve often wished my father-in-law had sat down with me before Kay’s mother and I were married and told me more about himself. Young people are so apt to take things for granted and expect things that aren’t possible.”

“That’s right,” said Buckley.

Mr. Banks glanced at him quickly, but Buckley was fumbling with the catch on his briefcase.

“Well, to begin with—” said Mr. Banks nervously.

At the end of fifteen minutes Buckley knew more about Mr. Banks’ affairs than Mrs. Banks had been able to dig out in a lifetime. He listened with grave attention and nodded understandingly from time to time. Mr. Banks’ feeling that he was consulting his doctor became stronger as he went on. When he had finished if Buckley had pulled a stethoscope out of his briefcase and asked him to strip to the waist he would have complied without question. Instead Buckley removed a large sheaf of papers from the briefcase.

“I’ve brought some papers,” he said, somewhat unnecessarily.

“Soup’s on,” cried Mrs. Banks from the livingroom door, in her gayest company manner. “My, you two look solemn. Come now or it will get cold.”

“That’s all right, my boy. We’ll do your side later.”

• • •

Kay jumped up from the table before they had finished dessert. “Come on, Buckley, we’re late. Sorry, Mom, we promised to meet the Bakers and go to the movies. Pops kept Buckley talking too long. You don’t mind if we skip the dishes do you?”

“Of course not, dear. Run along.”

• • •

“Did you have a good talk with Buckley?” she asked as they cleared the dining-room table.

“Very satisfactory,” said Mr. Banks moodily.

4

THE NEWS IS BROKEN

It had been agreed that only a few intimate friends and members of the family were to be told before the engagement was formally announced in the papers. Kay said this involved a cocktail party for everyone but the relatives. She would write them when she had a chance.

The news was too big, however. It was more than she could cope with. She told everyone she met—in absolute confidence, of course—with the result that in twenty-four hours the only ones who did not know were those who would be mortally hurt if not told first.

Mr. Banks said that, under the circumstances, the cocktail party was about as necessary as a G. I.’s pajamas. Kay said that was

ridiculous

. She had only told a few people and they had

promised

to say nothing about it and

everybody

announced their engagement to their close friends at a cocktail party whether they knew about it already or

not.

And so it was that, a few days later, Mr. Banks came out from town on the three-fifty-seven, composing an informal and, he hoped, dryly humorous little speech. It was to be about Kay as a little girl, Kay growing up and finally, in a big surprise climax, Kay announcing her engagement.

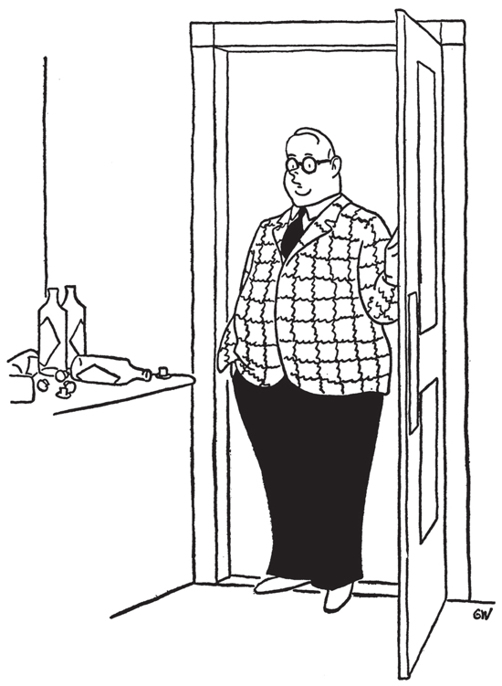

. . . Composing an informal and, he hoped, dryly humorous little speech.

She had estimated that there would be between twenty-five and thirty people at the party. Experience had taught him that on this basis he could expect between thirty-five and fifty. In the pantry he stared with a sinking heart at the neatly arranged phalanxes of glasses that Mrs. Banks had borrowed during the day from unwilling friends. Clearly he hadn’t thought this thing through. How was any one man to make drinks for a crowd like that? It would take a trained octopus.

However, this was no time for panic. Decisive action was called for. Martinis for everybody. That would be simplest. With perhaps just a few old-fashioneds ready for those allergic to gin. He pulled two large pitchers from a cupboard and went to work.

Mr. Banks was a hospitable man and in many ways a generous one. There were limits, however. He groaned with pain as he listened to one bottle after another of his best gurgle its lifeblood into the pitchers. But when it was all done and he stood back to inspect the result, he realized that it had been a labor of love. He cherished a special fondness for these kids who had been running through his house for twenty years and whose names he could no longer remember now that they had suddenly grown up.

The early ones were arriving. He could hear the high-pitched entrance screams of the females. He wiped his hands on a dishcloth and was about to go out and greet them when the pantry door was blocked by a rosy-cheeked young man with a disarming smile.

“How are you, sir?”

“I’m fine, how are you?” said Mr. Banks, trying to remember where he had seen him before. “Are they starting in already?”

“That’s it, sir. I was wondering if I could have four old-fashioneds.”

“No martinis?” suggested Mr. Banks.

“Oh, no indeed, sir. That’s very kind of you. Just old-fashioneds.”

Mr. Banks filled four of his emergency glasses with ice cubes and pushed them down the pantry shelf. “Thank you, sir. That’s service,” said the young man. His place was immediately taken by a stout youth with horn-rimmed glasses.

“Sir, four old-fashioneds and one scotch and soda.”

“I haven’t any scotch,” said Mr. Banks. He hoped that his voice did not betray the fact that he had just hidden three bottles in the end cupboard behind Mrs. Banks’ flower vases.

The stout young man looked nonplused. He was silent for a moment as he considered this unexpected situation from every angle.

“I don’t know, sir. I guess bourbon and soda will do.”

Mr. Banks, irritated by a sense of guilt, poured a highball from a bottle labeled “Whiskey—A Blend.” “Wouldn’t those people like martinis?” he asked.