Fenway Park (11 page)

Authors: John Powers

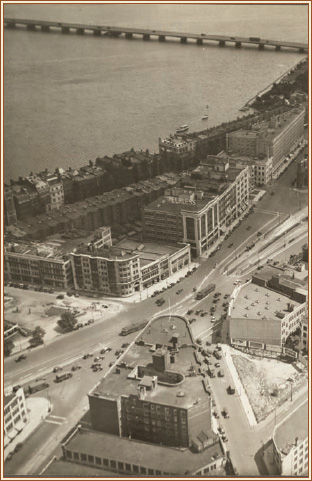

CHAOTIC KENMORE SQUARE

When the Red Sox play a home game, Kenmore Square is the conduit for the lion’s share of the more than 35,000 fans who converge on the ballpark. And like the Fenway neighborhood itself, Kenmore Square didn’t exist until the late 19

th

century.

The land the square sits on was then called Sewall’s Point, and it was pretty much surrounded by tidal salt marsh. Sewell’s Point was connected to downtown Boston by a narrow road (later to become Beacon Street) that ran atop a dam along the Charles River. When the Back Bay was filled in the late 19

th

century, the former dam road became Beacon Street, which connected to Brookline Avenue. A short time later, Commonwealth Avenue was constructed, and the three roads converged at what became known as Governor’s Square.

Governor’s Square (renamed Kenmore Square in 1932) became an important local transportation hub. The Peerless Motor Car Building on the west side of the square now houses Boston University’s Barnes and Noble Bookstore, but its main claim to fame is the Citgo sign on its roof; it was born in the 1950s as a Cities Services billboard, and it became the landmark neon beacon in the 1960s.

Because of the local college-student population, Kenmore Square and the streets close to the ballpark feature plenty of restaurants, cafes, and music venues. The most famous jazz club was Storyville, which was located at the Hotel Buckminster starting in 1950. Legends such as Dave Brubeck, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, and Sarah Vaughan played the club, which was in the ground-floor space of the Buckminster now occupied by Pizzeria Uno. The legendary rock club The Rathskeller, a.k.a. “The Rat,” played grimy host to some of rock music’s great bands in the 1970s and 1980s as they paid their dues, including The Police, the B-52s, R.E.M., U2, the Ramones, Tom Petty, Blondie, and Sonic Youth. It closed in 1997, and its site is now occupied by the Hotel Commonwealth, which opened in 2003.

On Patriots Day, more than 20,000 official runners pass through the square on the home stretch of the Boston Marathon, the world’s oldest annual marathon. Hundreds of thousands of spectators root the runners on, and the square offers a convergence of race day and Red Sox fans spilling out of the traditional 11 a.m. holiday game.

The square was once noted for its hotels, including the Buckminster, at the corner of Beacon Street and Brookline Avenue, which was designed by Stanford White. It was the site of the first network radio broadcast, and it also played a part in the infamous “Black Sox” baseball scandal. On Sept. 18, 1919, the same day that the Chicago White Sox defeated the Red Sox, 3-2, at Fenway, bookmaker and gambler Joseph “Sport” Sullivan went to the hotel room of Arnold “Chick” Gandil, White Sox first baseman. There they hatched a plot to fix the 1919 World Series, which was to start 13 days later.

In 1915, the Kenmore Apartments building opened at the corner of Kenmore Street and Commonwealth Avenue. It later became the Hotel Kenmore, an elegant, 400-room operation that was once Boston’s baseball headquarters—at one time in the late 1940s when the Braves still played in Boston, all 14 visiting major-league clubs stayed there. Countless trades were made, managers hired and fired, and post-game parties featured celebrities of the day.

“As I grew up, I knew that [Fenway Park] was on the level of Mount Olympus, the Pyramid at Giza, the nation’s Capitol, the czar’s Winter Palace, and the Louvre—except, of course, that it is better than all those inconsequential places.”

—Former Major League Baseball Commissioner Bart Giamatti

After key injuries led to a ruined July, the club rallied with a strong finish and flirted with third place before slipping back to fifth. But that would be the best showing for more than a dozen years as the talent exodus to the Bronx continued during the offseason. Frazee swapped shortstop Everett Scott, who’d played nearly 1,100 games for Boston, plus pitchers “Sad Sam” Jones and “Bullet Joe” Bush for shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh and three hurlers. While critics lambasted the owner for continuing his yard sale, his money had paid for the furnishings. “It is Frazee’s team,” the

Globe

’s James O’Leary reminded readers, “and if he has goldbricked himself he is the one who will suffer.”

By Opening Day in 1922, nobody from the 1918 champions remained on the Red Sox roster. Even the stockings had been changed to ones with a dark stripe. “Picking red socks for the boys must have been left to someone who is color-blind,” Mel Webb observed in the

Globe

.

Though the club won four of five from the Yankees at home in late June, Boston couldn’t replace Jones and Bush, who won 39 games for New York that year. After their rotation fell apart, the Sox quickly sank from sight in July, dropping six in a row to the Indians and Tigers (the last by a 16-7 count). The club ended up losing 93 games, its most in a season since 1905, and finished in the cellar 33 games behind the Yankees. Since 1915, that had been the residence of the Athletics. Except for one season, Boston would be the new annual tenant there until Tom Yawkey bought the club in 1933.

That was the end for Duffy, who was kept on as a scout and “general all-round man.” In came Frank Chance, the “Peerless Leader,” who as player-manager had led the Cubs to world championships in 1907 and 1908 and to the National League pennant in 1906 and 1910. Chance, who had no illusions about what he was inheriting in the Hub, reckoned that it would take at least three years to transform the Sox into contenders.

With only a handful of regulars returning, the roster obviously was a reconstruction zone in 1923. And while Frazee predicted that the club “will be the finest, smartest lot of youngsters ever hired by a major-league ball club,” Boston essentially had become a minor-league franchise. After losing the first four games in New York, the Sox had dropped to the bottom by May 12 and never inched higher than sixth for the duration. After a brutal 27-3 loss at Cleveland on July 7—when reliever Lefty O’Doul gave up a club-record 13 runs in the sixth inning—Chance knew that the task exceeded his enthusiasm and endurance. “I have a one-year contract and that is enough,” he told a former Cubs director.

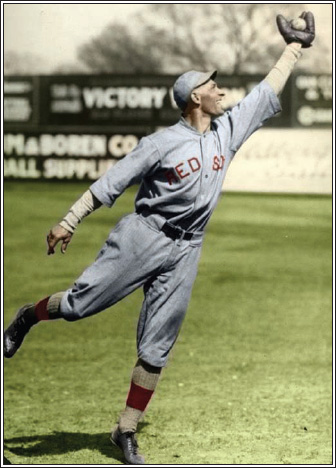

Michael William “Leaping Mike” Menosky played left field for the Red Sox after Babe Ruth was sold to the Yankees. He was with the Red Sox for four years, during which time he hit a total of nine home runs.

HARRY FRAZEE: THE MAN BEHIND THE CURSE

BY DAN SHAUGHNESSY

On Monday, January 5, 1920, the Harvard University football team, still celebrating its New Year’s Day, 7-6, Rose Bowl victory over Oregon, rolled eastward into Chicago on the California Limited. In Washington, D.C., in a 5-4 decision rendered by Justice Louis D. Brandeis, the Supreme Court upheld the right of Congress to define intoxicating liquors, sustaining the constitutionality of provisions in the Volstead Act. Elsewhere, the last of the U.S. troops in France made their way home across the Atlantic, and a New York Supreme Court justice ruled that it was not immoral for women to smoke cigarettes.

There was one more bit of news that day. Late in the afternoon, Harry Frazee held a press conference and announced that slugger-pitcher George Herman “Babe” Ruth had been sold for cash to the New York Yankees.

“The price was something enormous, but I do not care to name the figures,” said Frazee that day. “No other club could afford to give the amount the Yankees have paid for him, and I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble.”

Prohibition was 11 days away when Frazee made this move, which would drive Sox fans to drink.

There was some outrage when the Ruth transaction was announced but none of the hysteria that would accompany such a transaction in today’s age of media overkill. The sale of Babe Ruth to Gotham was front-page news in all the Boston papers. John J. Hallahan of the

Evening Globe

led his story with: “Boston’s greatest baseball player has been cast adrift. George H. Ruth, the middle initial apparently standing for ‘Hercules,’ maker of home runs and the most colorful star in the game today, became the property of the New York Yankees yesterday afternoon.” A newspaper cartoon showed Faneuil Hall and the Boston Public Library wearing “For Sale” signs.

In his autobiography, Ruth admitted, “As for my reaction over coming to the big town, at first I was pleased, largely because it meant more money. Then I got the bad feeling we all have when we pull up our roots. My home, all my connections, affiliations and friends were in Boston. The town had been good to me.”

Frazee’s name was mud in Boston, just as it is now. One night he was out in Boston with character actor Walter Catlett. In an attempt to impress a pair of young ladies, Frazee had a cab driver take the group to Fenway Park. He got out of the cab and proudly displayed his baseball empire. The cab driver overheard the boasts and asked if this passenger was in fact Harry H. Frazee, owner of the Red Sox. Frazee said he was, and the driver decked him with one punch.

On July 11, 1923, Frazee sold the Red Sox to Robert Quinn for $1.25 million. The 1923 Red Sox did not have one player left from the championship season of 1918. The man who did the dirty deed didn’t care anymore. While the Sox stumbled through the Roaring Twenties, Frazee finally hit the mother lode in 1925 with No, No, Nanette. It had a New York run of 321 performances and was one of the most successful shows of the 1920s, earning more than $2.5 million for Frazee.

But Frazee didn’t have much time to enjoy his money. The shows after Nanette didn’t do as well, and on June 4, 1929, four weeks shy of his 49

th

birthday, Harry H. Frazee, or “Big Harry” as he is known in family lore, died of kidney problems at his home in New York City. Frazee always said that the best thing about Boston was the train to New York, and New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker was at Frazee’s bedside when he died.

Ruth went on to establish himself as his sport’s greatest performer. He set a major-league record with 60 home runs in 1927 and was still the idol of millions of Americans when he died of cancer in 1948. His record of 714 career home runs stood until Hank Aaron passed him in 1974. He was one of the original five players enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

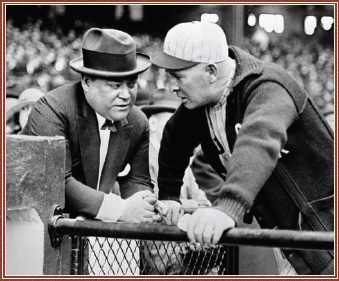

Red Sox owner Harry Frazee (left) and manager Frank Chance huddled at Yankee Stadium in 1923. Frazee sold the franchise and park in July of that year.