Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (26 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

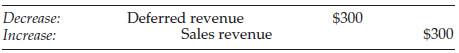

Then next year, management would simply release that “pent-up” deferred revenue into revenue.

Saving Up for a “Rainy Day”

During the late 1990s, software giant Microsoft faced enormous scrutiny over its alleged monopolistic practices by both the U.S. Department of Justice and its European Union counterpart overseeing antitrust regulation. Presumably, the last thing Microsoft wanted to showcase was skyrocketing revenue and profits, as this would probably have become fodder for regulators. It certainly would have been tempting for the company to delay recognition of unexpectedly high revenue by deferring it to a later period and storing it on the Balance Sheet in the form of unearned revenue.

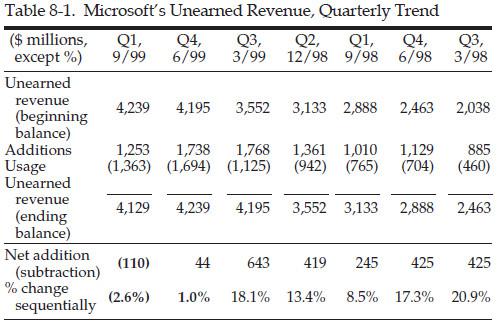

As shown in Table 8-1, Microsoft’s unearned revenue account grew by hundreds of millions of dollars every quarter from March 1998 to March 1999. Indeed, this reserve more than doubled over this period, from $2.038 billion at the beginning of 1998 to $4.195 billion at March 1999. Then, suddenly the growth abated in the June 1999 quarter, with the company adding only as much unearned revenue as it was using.

While several factors probably contributed to this big buildup and then sudden drop in unearned revenue, one allegation at the time was that Microsoft was building reserves to save up for a rainy day. When revenue fell by 6.6 percent sequentially in the September 1999 quarter, investors questioned whether that rainy day had arrived.

Another factor contributing to the decline in deferred revenue was a June 1999 change in revenue recognition policy that caused Microsoft to recognize more revenue up front on certain software sales. In adopting a new rule (SOP 98–9), Microsoft decided to adjust its estimates to increase the amount of revenue it would recognize upon shipment of the software and reduce the amount it would treat as unearned. (See Microsoft’s disclosure.) Regardless of the legitimacy of this policy change, the impact was to release some of Microsoft’s “pent-up” deferred revenue.

EXCERPTS FROM MICROSOFT’S REVENUE RECOGNITION

DISCLOSURE, 1999 10-K

Upon adoption of SOP 98-9 during the fourth quarter of fiscal 1999, the Company was required to change the methodology of attributing the fair value to undelivered elements. The percentages of undelivered elements in relation to the total arrangement decreased, reducing the amount of Windows and Office revenue treated as unearned, and increasing the amount of revenue recognized upon shipment.

The percentage of revenue recognized ratably decreased from a range of 20% to 35% to a range of approximately 15% to 25% of Windows desktop operating systems. For desktop applications, the percentage decreased from approximately 20% to a range of approximately 10% to 20%.

The ranges depend on the terms and conditions of the license and prices of the elements. The impact on fiscal 1999 was to increase reported revenue $170 million. [Italics added for emphasis.]

Stretching Out Unexpected Gains over Several Years

In reality, few companies have the sort of solid sustained growth that would allow them to confidently squirrel away billions of dollars in revenue earned for a later period and still meet Wall Street targets. More commonly, however, companies use EM Shenanigan No. 6 when they are the recipients of a windfall gain.

Shifting Windfall Gains to Future Periods.

Consider the Florida-based chemical company W. R. Grace. In the early 1990s, Grace’s health-care subsidiary experienced a significant and unanticipated increase in revenue as a result of changes in Medicare reimbursements. Management deferred some of the unanticipated income by increasing or establishing reserves. These reserves ballooned to more than $50 million by the end of 1992. By creating these reserves and then releasing some of them, the subsidiary reported steady earnings growth of from 23 to 37 percent between 1991 and 1995. The actual growth rates ranged from

minus 8 percent to plus 61 percent

. When Grace sold this subsidiary in 1995, it released the entire excess reserve into income, labeling it a “change in accounting estimate.” Alert investors should have considered that earnings boost unsustainable.

Shifting Huge Trading Gains to the Future.

Enron’s infamous manipulation of the California energy markets in 2000–2001 earned the company huge windfall profits in its trading division. The profits were so large that management decided to save some for future quarters, which, according to the SEC, was done in order to

mask the extent and volatility of its windfall trading profits

. Compared to the rest of Enron’s shenanigans, this scheme was fairly straightforward: simply defer some of the trading gain by storing it in a reserve on the Balance Sheet. These reserves came in handy and helped Enron avoid reporting large losses during difficult periods. By early 2001, Enron’s undisclosed reserve accounts had ballooned to over $1 billion. The company then improperly released hundreds of millions of dollars of these reserves to ensure that Wall Street’s expectations were met. Ironically, there would be no future quarters in which to release unused reserves, as Enron imploded in October 2001 and probably needed to show all the revenue that it had held back for the “rainy day.” That rainy day surely had arrived in October 2001—

a Category Five hurricane for investors, with no survivors!

Using Reserves to Smooth Income Is a Serious Transgression.

Smoothing of income is not an uncommon strategy for management to engage in, as Wall Street rewards solid and predictable profit growth. However, the use of reserves to shift income to a later period can be as serious an income manipulation ploy as recording revenue too soon (EM Shenanigan No. 1). In both cases, the effect is misleading financial results. When revenue is recorded too early, future income is recorded in the current period; conversely, with income smoothing, current income is shifted to a future period.

2. Improperly Accounting for Derivatives in Order to Smooth Income

Companies with healthy businesses can engage in income-smoothing shenanigans to give the illusion of nice, steady, predictable results. Consider mortgage giant Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac or Freddie) and its desire to portray very smooth earnings despite a period of volatile interest-rate movements. Freddie’s attempts to smooth earnings went to the extreme and led to an over $5 billion fraud.

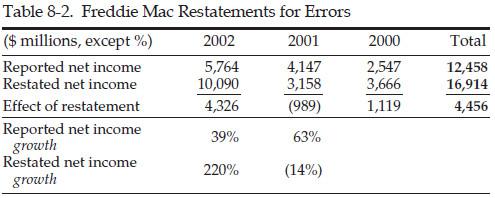

Volatile Interest-Rate Market Makes “Steady Freddie” Much Less Predictable. Freddie’s earnings manipulation was related largely to its incorrect accounting for derivative instruments, loan origination costs, and reserves for losses. When the corrected numbers were released, we learned a fascinating thing about the scandal: the company actually wound up understating its profits. From 2000 to 2002, Freddie Mac underreported net income by nearly $4.5 billion. As shown in Table 8-2, Freddie’s smoothing techniques allowed it to report earnings growth of 63 and 39 percent in 2001 and 2002, when in reality, earnings growth was a much more volatile negative 14 percent in 2001 and positive 220 percent in 2002.

What could have led Freddie to embark on this course? Well, Wall Street had come to expect steady and predictable earnings from the company. A challenge arose in 2000 with the implementation of a new accounting rule that created enormous volatility in the company’s investment activities involving derivatives (SFAS No. 133). It quickly became clear to management that the change in accounting would create huge windfall gains for the company.

Initial estimates of the gain were in the hundreds of millions, but they soon ballooned to the billions. For most of us, billions of dollars in windfall gains would be great news. To Freddie Mac, however, this was a problem. The company’s rock-solid stock price was largely built on its ability to produce steady and predictable earnings. It certainly earned its nickname “Steady Freddie.” So, ever conscious of its reputation for pleasing Wall Street, Freddie schemed to hold back a large part of the windfall gain and release portions of it when needed to smooth earnings.

Unlike the frauds at Enron and WorldCom, the focal point of Freddie’s fraud was not to mask a deteriorating business, but rather to maintain its image as a predictable earnings generator. In other words, the ultimate gain was not earnings creation but earnings smoothing. Both types of shenanigans clearly violate accounting rules and misrepresent the economic reality to investors. The biggest difference between companies that create earnings out of thin air and those that smooth is that the latter group is likely to consist of healthy companies that are simply attempting to portray a more predictable earnings stream.

Fannie Trumps Freddie in Income Manipulation.

Fannie Mae, the larger competitor of Freddie Mac, had a similar desire and incentive to present a steady stream of earnings growth in the volatile and unpredictable mortgage market. According to the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (Fannie’s regulator), management also had a strong desire to achieve profit targets that would trigger maximum bonuses, which led it down the road of accounting gimmickry.

Like Freddie Mac’s, Fannie Mae’s business is subject to a substantial amount of interest-rate risk, and the company therefore used derivatives extensively to manage this risk. The largest part of Fannie’s accounting fraud involved improper accounting for these derivatives. To better understand how Fannie abused the accounting, let’s first discuss some basics of derivatives accounting. (Also see the associated accounting capsule on the next page.)

Companies often use derivatives to hedge their exposure to an asset or liability. For example, if a company has a receivable in a foreign currency, it may use a derivative to hedge its currency exposure, and by doing so, “lock in” the amount of cash that it will eventually receive. Accounting rules for derivatives (SFAS 133) provide a framework for categorizing hedges into groups based on different attributes, such as their purpose and effectiveness. The categorization is important because it determines whether or not fluctuations in the derivative will affect earnings. For example, all quarterly gains or losses from the change in value (i.e., the mark-to-market adjustment) on a hedge that is deemed to be “ineffective” should be recognized as current-period income. Yet for certain types of “effective” hedges, the change in value does not affect earnings at all. As you might imagine, the categorization of hedges is a very sensitive and important decision. (We know that this can get a bit complicated, and maybe Fannie also got a bit confused—or simply ignored the rules.)