Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (32 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

also portend inflated CFFO as well.

Tip:

If you suspect a company of recording bogus revenue, you must also consider that it may also have recorded bogus operating cash flow.

Be Wary Around Pro Forma CFFO Metrics.

Delphi steered investors away from its reported CFFO, and instead highlighted a cash flow measure that it defined itself and confusingly labeled “Operating Cash Flow.” Normally investors use the terms CFFO and

operating cash flow

interchangeably; however, Delphi defined them very differently. (More on this in Part 4, “Key Metrics Shenanigans.”)

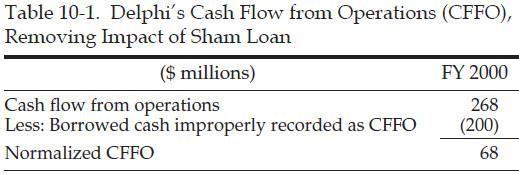

In FY 2000, Delphi reported $268 million in CFFO on its Statement of Cash Flows; however, its self-defined “Operating Cash Flow” (reported in the earnings release) was $1.636 billion. No, we’re not kidding—a differential of an amazing $1.4 billion! Careful investors would have noticed this shenanigan and immediately become skeptical about the company, as the level of trickery was astounding and inexcusable. (Stay tuned for more on this $1.4 billion differential in Chapter 14.) Of course, even the $268 million in reported CFFO was inflated, as it included the sham sale of inventory to the bank discussed previously. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) must have had a field day when it sorted through all of Delphi’s schemes and charged the company with fraud.

Not only did Delphi create a misleading substitute for CFFO, but it routinely highlighted the strength of this number to investors in the title of its quarterly earnings reports. Investors should be cautious whenever management places such an intense focus on a company-created cash flow metric that covertly redefines the very important CFFO. Of course, management’s creative use of metrics may not always be indicative of fraud; however, investors should nonetheless ratchet up their normal level of skepticism.

Complicated Off-Balance-Sheet Structures Raise the Risk of Inflated CFFO

We have already outlined several ruses perpetrated by Enron, particularly its use of off-balance-sheet vehicles such as special-purpose entities. Some of the schemes that Enron concocted helped it present a misleadingly stronger CFFO. For example, Enron would create such a vehicle and then help it borrow money by co-signing its loans. The Enron-controlled vehicle then used the cash received to “purchase” commodities from Enron. Enron recorded the cash received as an Operating section inflow (CFFO) from the “sale” of the commodities.

The structure of these transactions may seem complicated, but the economics were quite simple: Enron entered into arrangements to sell commodities to itself. The problem was that it recorded only half of the transaction—the part that reflected the cash inflows. Specifically, Enron recorded the “sale” of the commodities as an Operating inflow, but ignored the offsetting outflow from the vehicle’s “purchase” of these commodities. If Enron had recorded this transaction in line with its economics, the cash inflow would have been deemed a loan and hence recorded as a Financing inflow. This trick allowed Enron to embellish its CFFO by billions of dollars, to the detriment of its Financing cash flow—and, of course, of its investors.

2. Boosting CFFO by Selling Receivables Before the Collection Date

In the previous section, we discussed how Delphi and Enron created a dangerous scheme in their Twins genetics labs that allowed them to record completely bogus cash flow from operations. In this section, we discuss how companies might boost CFFO with a transaction that is considered completely appropriate and is actually quite popular: selling accounts receivable. However, the way management presents these transactions on its financial statements often leads to a great deal of confusion for investors.

Turning Receivables into Cash Even Though the Customer Has Yet to Pay

Companies often sell accounts receivable as a useful cash-management strategy. These transactions are actually quite simple: a company wishes to collect on its receivables before they come due. The company finds a willing investor (often a bank) and transfers the ownership of some receivables to it. In return, the company pockets a cash payment for the total amount of receivables, less a fee.

Let’s think about the underlying transaction, its purpose, and the other party’s interest. Does this arrangement sound like a financing transaction or an operating one? Many people would agree that an arrangement in which a bank simply cuts you a check looks strikingly similar to an old-fashioned loan—nothing more than a form of financing, particularly since management determines the timing and the amount of cash received. They therefore expect that this transaction will not affect CFFO. However, the rules state otherwise.

The appropriate place to record cash received from the sale of receivables would be as an Operating, not a Financing inflow. Why Operating? Because the cash received could be viewed as representing collections from past sales. Indeed, this is one of many “gray areas” that cause confusion among even the savviest investors.

Accounting Capsule: Selling Accounts Receivable

It is important to recognize when a company is selling its receivables, as these transactions are recorded as CFFO inflows. There are different ways in which companies can sell their receivables, including factoring transactions and securitizations. Keep an eye out for these key words in financial statements.

•

Factoring:

The simple sale of receivables to a third party, often a bank or a special-purpose entity.

•

Securitization:

The sale of receivables to a third party (often a special-purpose entity) for the purposes of creating new financial instruments (“securities”) by repackaging the receivable inflows.

Selling Accounts Receivable: An Unsustainable Driver of Cash Flow Growth

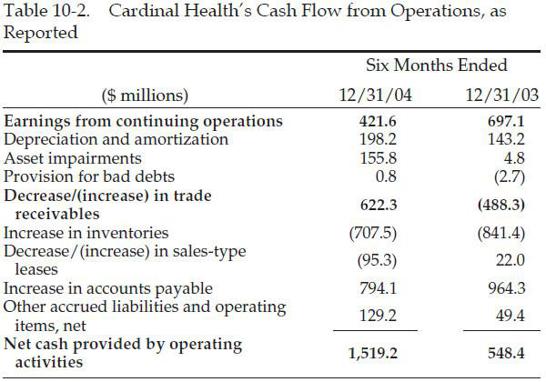

In 2004, pharmaceutical distributor Cardinal Health needed to generate a lot more cash. So, management decided to sell accounts receivable to help the company raise a substantial amount of cash very quickly. By the end of the second quarter (December 2004), Cardinal Health had sold $800 million in customer receivables. This transaction was the primary driver of the company’s robust $971 million in CFFO growth in December 2004 over the prior-year period.

While Cardinal Health certainly was entitled to any cash received in exchange for its accounts receivable, investors should have realized that this was an

unsustainable

source of CFFO growth. Cardinal Health essentially collected on receivables (from a third party, rather than from its customers) that would normally have been collected in future quarters. By collecting the cash earlier than anticipated, the company essentially shifted future-period cash inflows into the current quarter, leaving a “hole” in future-periods’ cash flow. The transfer of cash flow to an earlier period is likely to result in disappointing future CFFO— unless, of course, management finds another CF Shenanigan to plug the hole. (Companies never stop looking for and finding new tricks, which is why a fourth edition of Financial Shenanigans will surely be needed in the not-too-distant future.)

Watch for Sudden Swings on the Statement of Cash Flows

. Even novice investors could have identified that something important had changed in Cardinal Health’s accounts receivable, and that CFFO growth was largely driven by this change. Look at the company’s Statement of Cash Flows in Table 10-2. Notice that the $971 million increase (from $548 million to $1.5 billion) in CFFO had been driven primarily by a $1.1 billion “swing” in the impact of receivables. Specifically, in the six months ending December 2004, the change in accounts receivable represented a cash inflow of $622 million, while in the previous year, the change in accounts receivable had contributed a cash

outflow

of $488 million. Without doubt, the massive receivable sale, not an improvement in Cardinal Health’s core business, produced the impressive CFFO improvement. To emphasize, investors should focus not only on

how much

CFFO grew, but also on

how

it grew—a very big difference.

Sudden “swings” like that at Cardinal Health signal the need to explore more deeply. In this case, you would have found that the company began selling more accounts receivable. This was fairly easy to find, and the company clearly did nothing improper. In fact, the company was very forthcoming, disclosing the accounts receivable sales clearly in its earnings release as well as in the 10-Q filing (although disclosing it on the Statement of Cash Flows would be preferred). While perhaps casual or lazy investors were too easily impressed with Cardinal Health’s ability to grow its CFFO, savvy investors would certainly have realized that the growth came from a nonrecurring source.

Stealth Sales of Receivables

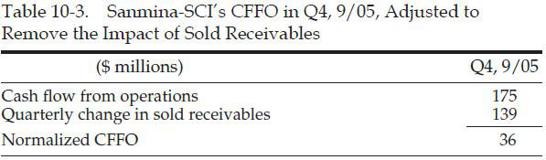

Unlike Cardinal Health, which was relatively forthcoming with its disclosure, some companies try hard to keep investors in the dark when their CFFO benefits from the sale of receivables. Take, for instance, the case of a certain electronics manufacturer. Sanmina-SCI Corporation reported its fourth-quarter results for September 2005 in early November. In the earnings release, Sanmina decided to prominently display its strong CFFO as one of its fourth-quarter “highlights.” Accounts receivable had decreased, and Sanmina also proudly pointed out the decline in receivables near the top of the release.

But the earnings release didn’t tell the whole story. Nearly two months later, deep in the 10-K filed on December 29, 2005, while many investors were on holiday, Sanmina disclosed what had really happened:

the primary driver of CFFO in Q4 was the sale of receivables

. Sanmina reported that $224 million in receivables that it had sold were still subject to recourse at the end of the quarter, according to a report by RiskMetrics Group. This was quite an increase from the $84 million reported in the previous quarter. Sanmina had been quietly selling receivables for the past couple of quarters, but never in this magnitude. As shown in Table 10-3, without this increase in receivables sold, Sanmina’s CFFO would have been $139 million lower, falling to $36 million instead of the reported $175 million.

Tip:

When normalizing CFFO to exclude the impact of sold receivables, use the change in sold receivables outstanding at the end of the quarter. This way, you account for the receivables that were outstanding last quarter, but collected during this one.