Flags of Our Fathers (23 page)

Read Flags of Our Fathers Online

Authors: James Bradley,Ron Powers

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Non-Fiction, #War

Now Smith took the podium. He somberly predicted large casualties, a hard fight. As his words sank in among the correspondents he said proudly and quietly: “It’s a tough proposition. That’s why my Marines are here.”

As the Old Warrior sat down his eyes were misty. Iwo Jima would be his last battle, the last time he would command “my Marines.”

Then a special guest rose to speak. He was dressed in Marine fatigues with no insignia of rank. He was the big boss, Navy Secretary James Forrestal, out to witness the Navy’s largest operation in its history. And he made clear that he knew who would bear the brunt of this campaign:

In the last and final analysis it is the guy with the rifle and machine gun who wins the war and pays the penalty to preserve our liberty. My hat is off to the Marines. I think my feelings about them are best expressed by Major General Julian Smith. In a letter to his wife after Tarawa he said, “I never again can see a United States Marine without experiencing a feeling of reverence.”

The room was still as Forrestal sat down. Howlin’ Mad’s face beamed with a proud smile.

Admiral Turner broke the silence. “Are there any questions?”

From the back row a correspondent asked, “When’s the next boat to Pearl Harbor?”

The Japanese on Iwo certainly did not share Forrestal’s opinion of the Marines. These troops had never fought Americans and by their standards the Marines were cowardly, known to refuse the honorable choice of death and choose surrender. The Marines fought for publicity and had materialistic desires, their government pamphlets assured them. And worst of all, they didn’t fight with spiritual incentive like the Japanese fighting man, but instead depended upon their material superiority.

Veteran combat correspondent Robert Sherrod, who had landed on Tarawa and who would also land on Iwo, felt differently. He wrote that it was easy to say that American industrial power was winning the war. “But no man who saw Tarawa, Saipan…would agree that all the American steel was in the guns and bombs. There was a lot, also, in the hearts of the men who stormed the beaches.”

For the boys of Easy Company, their year of special training at Camp Pendleton and Camp Tarawa had prepared them to pay any price for one another, as a team, as a band of brothers. They would fight for their company, their platoon, their squads and fire teams. And it would be the ties at this level that would determine the outcome of the battle. Ira had written home: “There is real friendship between all us boys; and I don’t think any of us would take $1000 to separate from the others. We trust and depend on one another and that’s how it will be in combat. These boys are all good men.”

The Japanese enemy would fight to the death for the Emperor. That motive made them formidable. But these boys would fight to the death for one another. And that motive made them invincible.

As Robert Leader would write as a full professor of fine arts at Notre Dame in 1979:

It was like being on a winning athletic team and everyone was playing over his head. Can you possibly imagine the unspoken affection we felt for each other? An affection that allowed men to offer their lives daily for each other without hesitation and, I suppose, without understanding. And yet, to place oneself between danger and one’s people is the ultimate act of love.

Mike, Harlon, Franklin, Ira, Rene, and Doc were about to enter a battle against an underground enemy that had endured the Pacific’s most intense bombing of World War II and had not been disturbed. The only way the cave kamikaze could be overcome was by direct frontal assault, young American boys walking straight into Japanese fields of fire.

It would be a battle pitting American flesh against Japanese concrete. The boys would have only their buddies to depend upon, buddies who were willing to die for one another. As soon they would.

The evening of D-Day minus one, February 18, a date that nine years later would become my birthday, my father and the assault troops still could not see their objective. Everything was timed down to the minute. Their churning craft would approach Iwo Jima on schedule, only just before it was time to assault the beaches.

Each boy was quiet now, lost in his private thoughts. Their confidence must have been shaken when, that night, Tokyo Rose named many of their ships and a number of the Marine units. She assured the Americans that while huge ships were needed to transport them to Iwo Jima, the survivors could later fit in a phone booth.

The opposing commanders tried to get some sleep before battle. Howlin’ Mad comforted himself with his Bible in his cabin on the

Eldorado

.

Kuribayashi was also in his personal quarters—a system of caves and tunnels seventy-five feet below the surface of Iwo Jima. Lying in his small concrete cubicle. The dim candlelight illuminated the “Courageous Battle Vow” posted on the wall, as he had ordered it posted on the walls of all the bunkers, caves, and blockhouses on the island. It read:

We are here to defend this island to the limit of our strength. We must devote ourselves to that task entirely. Each of your shots must kill many Americans. We cannot allow ourselves to be captured by the enemy. If our positions are overrun, we will take bombs and grenades and throw ourselves under the tanks to destroy them. We will infiltrate the enemy’s lines to exterminate him. No man must die until he has killed at least ten Americans. We will harass the enemy with guerrilla actions until the last of us has perished. Long live the Emperor!

There is no record of what Kuribayashi’s last thoughts were before he fell off to sleep that night. But in a broadcast to the mainland on Radio Tokyo he had said, “This island is the front line that defends our mainland, and I am going to die here.” And to his son Taro he had written, “The life of your father is just like a lamp before the wind.”

But there is one thought he had never shared with the 22,000 men he was about to lead to their deaths. He had written it years before to his wife when he was stationed in the United States, after traveling extensively across America: “The United States is the last country in the world Japan should fight.”

Seven

D-DAY

Life was never regular again. We were changed from the day we put our feet in that sand.

—PRIVATE TEX STANTON,

2ND PLATOON, EASY COMPANY

IT BEGAN EERILY, IN THE NIGHT:

A dark Pacific sky cut by hellish red comets, rising and descending in clusters of three, each descent followed by a distant explosion. Sleepless young Marines stood watching atop their LST’s, thirteen miles offshore.

To Easy Company’s Robert Leader of Cambridge, Massachusetts, it looked like heat lightning on a summer night. Through his daze, he heard a voice in the darkness utter what sounded like a fragment from a dream: “That’s Sulfur Island.” “What do you mean?” Leader murmured, not turning his eyes from the sky. The speaker beside him, a Navy crewman, replied: “Don’t you know? ‘Iwo Jima’ means Sulfur Island.”

The sun rose pink. The sky turned blue and clear. On the horizon, the sulfur island lay wreathed in smoke.

The date was February 19, 1945.

The cooks on the transport ships had provided a gourmet breakfast for the young men about to suffer and die: steak and eggs.

Doc awoke with the others, before dawn. The first words spoken to him were from a veteran: “Me, I’m experienced enough to dodge the bullets. You—well, you’ll probably get one right between the eyes.”

Mike had spent much of the night watching the shelling. Ed Blankenburger, who’d stood beside him, had been elated: Surely this barrage would all but obliterate the enemy. His optimism was shared by many of the boys. Seventeen-year-old Donald Howell, from Mercer City, Ohio, was so certain there would be no Japanese survivors that he relaxed on board with a book called

House Madam,

about brothels on the West Coast.

And so Blankenburger was surprised when, near dawn, he heard Mike say quietly: “I’m not coming back from this one, Ed.”

Over 70,000 Marines—the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Divisions—massed in the ships that had finally arrived at Island X, ready to hit the narrow two-mile beach in successive phases. Awaiting them, dug into the island and out of sight, 22,000 elite Japanese—the Rising Sun—who understood that they were to die.

At seven

A.M.

the boys of Easy Company walked down the metal steps of LST-481 and into the yawing holds of their assigned amphibious tractors. All the terrifying practice that Doc Bradley had put in scrambling down those treacherous net ladders in Hawaii had gone for naught. But there was plenty of terror left. “I was petrified when we got into those amtracs,” Corpsman Vernon Parrish, a close friend of Doc’s, recalled. “I was new to battle but I could sense that even the veterans were scared.” Parrish’s fears were hardly calmed when one veteran, gazing at Iwo, said out of the corner of his mouth: “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re going to learn more in the first five minutes there than you did in the whole year of training you’ve been through.”

Now the first waves of tractors were loaded and surging toward the island at full throttle, kicking up white foam behind them, their turbine engines deafening to the helmeted young men packed inside, about twenty to a boat. Behind and above them was an overwhelming American force that controlled the sea and the air: in the sea, the armada at anchor, vessels stretching away from shore for ten miles; in the air, flights of Navy Hellcats swooping low to strafe Mount Suribachi, reshaping its contours with their firepower. In front of them lay the most ingenious and deadly fortress in military history. The Century of the Pacific was about to be forged in blood.

In those final moments before the first landing, many of the troops in the boats could still convince themselves that this was going to be no sweat. They could do this despite the evidence to the contrary around them: the doctors and medics with their surgical instruments and their operating tables ready to be set up on the beaches. The rabbis, priests, and ministers in their midst, prepared to wade ashore and risk their lives to comfort the dying. And the wooden crosses, the Stars of David, the body bags, that later boats would carry.

Maybe all that stuff would not be needed. Wasn’t the island being blown to bits even as the amtracs churned toward shore? The enormous battlewagons out in the ocean were blasting Iwo Jima with sheets of one-ton shells. The concussion of these great guns nearly capsized some of the smaller boats. Howlin’ Mad Smith himself would remember it as a barrage that blotted out all light “like a hurricane eclipse of the sun.”

In those final moments, a carefree kid aboard Doc’s amtrac could still serenade his buddies with Nelson Eddy/Jeanette MacDonald movie tunes. In those final moments, eighteen-year-old Jim Buchanan of Portland, Oregon, could still view the bombing as a beautiful tableau, like in a movie; the island nearly invisible beneath clouds of gray, yellow, and white dust from all the rockets and bombs. He turned to his buddy, a kid named Scotty, and asked hopefully: “Do you think there will be any Japanese left for us?”

Jim Buchanan could not possibly fathom what lay immediately ahead. None of them could.

The bombardment had not touched the subterranean

issen gorin

. They would have to be obliterated individually, up close, at tremendous cost. The Marines were hurtling toward a mutual slaughter that would involve nearly 120,000 Japanese and Americans on- and offshore, consume thirty-six days, kill or maim more than half the land combatants, and assume characteristics unlike anything in twentieth-century warfare.

The battle of Iwo Jima would quickly turn into a primitive contest of gladiators: Japanese gladiators fighting from caves and tunnels like the catacombs of the Colosseum, and American gladiators aboveground, exposed on all sides, using liquid gasoline to burn their opponents out of their lethal hiding places.

All of this on an island five and a half miles long and two miles wide. An area smaller than Doc Bradley’s hometown of Antigo, but bearing ten times the humanity. A car driving sixty miles an hour could cover its length in five and a half minutes. For the slogging, fighting, dying Marines, it would take more than a month.

The naval bombardment lifted precisely at 8:57

A.M.

At 9:02, just 120 seconds behind a schedule that had kicked in at Hawaii, the first wave—armored tractors, each mounted with a 75mm cannon—lumbered from the waves onto the soft black sands of Iwo Jima.

The first troop-carrying amtracs landed three minutes later, at 9:05

A.M.

, and behind them came hundreds more, each trailing a white wake. Easy Company rolled in on the twelfth wave at 9:55

A.M.

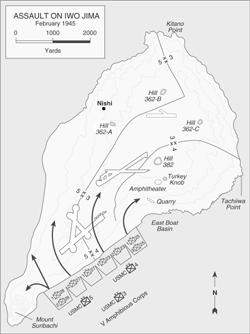

Easy was part of Harry the Horse’s 28th Regiment, whose special mission was to land on Green Beach One—the stretch nearest Mount Suribachi, just four hundred yards away, on the left—and then form a ribbon of men across the narrow neck of the island, isolating the fortified mountain and ultimately capturing it. This assignment meant that Easy Company would be part of a 2,000-man force fighting a separate battle from the main assault: Some of the 5th and the entire 4th Division would fan out toward the right and progress northward along the island’s length to engage the bulk of its defenders. Before the battle ended, part of the 3rd Division, originally seen as a reserve force, would be rushed into action.

The 28th’s was no small mission. As Howlin’ Mad Smith would later declare: “The success of our entire assault depended upon the early capture of that grim, smoking rock.”

And so the great tragic funneling from wide ocean to narrow beach had begun: hordes of wet, equipment-burdened boys slogging from the water, forming a tightly packed mass on the two-mile strip of beach. Targets in a shooting gallery.

The boys squinted upward at their assigned routes and the ugly, stunted mountain beyond. The beach slanted upward from a point some thirty yards from the edge of the surf; it rose in three terraces, each about eight feet high and sixteen feet apart. In peaceful times it might have resembled a gently curving amphitheater. In this context it was an amphitheater of death. The boys would have to climb not on hard white sand but on soft black volcanic ash that gave way and made each upward step a lingering effort.

The first wave of Marines and armored vehicles hit the shores. The vehicles bogged down immediately in the absorbent maw. The troops moved around them and began their cautious climb, unshielded, up the terraces.

It was all so quiet at first.

Perhaps the optimistic young Marines had been right. Perhaps it was over already. Donald Howell recalled, “When the landing gate dropped I just walked onto the beach. I was confident. Everyone was milling around. I thought this would be a cinch.”

The “cinch” lasted about an hour. The false calm was part of General Kuribayashi’s radical strategy: to hold off from firing at once, as every other Japanese force had done in the island campaign, and wait until the funneling attackers had filled the beach.

Easy Company had been ashore some twenty minutes and in their assembly area when the slaughter began.

Smoke and earsplitting noise suddenly filled the universe. The almost unnoticed blockhouses on the flat ground facing the ocean began raking the exposed troops with machine-gun bullets. But the real firestorm erupted from the mountain, from Suribachi: mortars, heavy artillery shells, and machine-gun rounds ripped into the stunned Americans. Two thousand hidden Japanese were gunning them down with everything from rifles to coastal defense guns. “It was so loud it was almost like it was quiet,” one stunned Marine remembered. To Lieutenant Keith Wells, Doc’s 3rd Platoon leader, Suribachi turned into a monstrous Christmas tree with blinking lights. The lights were gun barrels discharging ammunition at him and his men.

There was no protection. Now the mortars and bullets were tearing in from all over the island: General Kuribayashi had designed an elaborate cross fire from other units to the north. Entire platoons were engulfed in fireballs. Boys clawed frantically at the soft ash, trying to dig holes, but the ash filled in each swipe of the hand or shovel. Heavy rounds sent jeeps and armored tractors spinning into the air in fragments. Some Marines hit by these rounds were not just killed; their bodies ceased to exist.

More than Marines. “I was watching an amtrac to the side of us as we went in,” Robert Leader remembers. “Then there was this enormous blast and it disappeared. I looked for wreckage and survivors, but nothing. I couldn’t believe it. Everything just vaporized.”

In the same boat with Leader was Doc Bradley.

The boys on the beach scrambled forward. It was like walking through a pile of shell corn, said one. Like climbing in talcum powder, said another. Like a bin of wheat. Like deep snow.

Advancing tanks crushed those of the wounded who could not get out of the way. Others, unwounded, were shoved to their deaths by those behind them. “More and more boats kept landing with more guys coming onto the beach,” said Guy Castorini. “You had to just push the guy in front of you. It was like pushing him to his death.”

The shock of actual combat triggered bizarre thoughts and behavior. Some Marines dropped into a deep, terror-induced sleep amid the carnage and had to be kicked awake by their officers. Others clung to fastidious habits of civilian life. “I don’t smoke,” moaned a badly wounded boy who’d been offered a lit cigarette. Jim Buchanan, who had hoped there would be some Japanese left for him, became indignant when he realized what was happening. “Did you see those Japanese firing at us?” he screamed to the guy next to him. “No,” the leatherneck answered, deadpan. “Did you shoot them?” “Gee, no,” Buchanan replied. “That didn’t occur to me. I’ve never been shot at before.”

Phil Ward, leaping out of the amtrac that also contained my father, had a similar epiphany: “We’d had live ammo training in Hawaii, so I was used to the sound of bullets, but suddenly I realized why this was different. ‘Goddamn!’ I said. ‘These people are shooting at me!’”