Flapper (10 page)

Authors: Joshua Zeitz

“Mama and Daddy are here this week,” Zelda reported to Scott’s Princeton friend and best man, Ludlow Fowler.

30

“ … At present, I’m hardly able to sit down owing to an injury sustained in the course of one of [the] parties in N.Y. I cut my tail on a broken bottle and can’t possibly sit on the three stitches that are in it now—The bottle was bath salts—I was boiled—The place was a bathtub somewhere. None of us remember the exact locality.”

Judge Sayre was even less pleased when Scott and Zelda paid an extended visit in Montgomery. There, decked out in a Hawaiian hula outfit, Zelda and several other local women performed in the annual Les Mystérieuses ball. A member of the audience remembered that “one masker was doing her dance more daring than the others.… Finally the dancer in question turned her back to the audience, lifted her grass skirt over her head for a quick view of her pantied posterior and gave it an extra wiggle for good measure.” A dull murmur swept through the crowd. “That’s Zelda!” the younger set whispered.

For the young, celebrity couple, it was all as confusing as it was exhilarating.

“Within a few months after our embarkation on the Metropolitan venture,” Scott mused, “we scarcely knew any more who we were and we hadn’t a notion what we were.”

31

But they were having a good time. At the time, it seemed that was all that mattered.

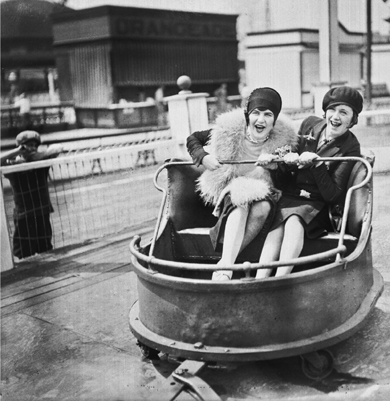

Two young women at Chicago’s White City amusement park, 1927.

6

I P

REFER

T

HIS

S

ORT

OF

G

IRL

I

T WAS

S

COTT

and Zelda’s good fortune to come of age in a country that was increasingly in the thrall of celebrity. The decade witnessed sensational murder trials like that of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two wealthy Chicago teenagers who killed a young boy just to see if they could get away with it, and Fatty Arbuckle, the portly Hollywood impresario who was tried twice—and finally acquitted—for the brutal rape and murder of a young actress. It gave rise to sports legends like Babe Ruth, who was just as renowned for his voracious culinary and carnal appetites as for his home run record, and Jack Dempsey, the heavyweight champion who by the mid-1920s had appeared in almost as many films as he did title fights.

In the decade following World War I, the average number of profiles that

The Saturday Evening Post

and

Collier’s

published nearly doubled.

1

Before 1920, most of these articles featured political and business leaders; now, more than half concerned key figures in entertainment and sports.

Scott and Zelda’s general notoriety might have satisfied their burning drive for recognition. But Scott’s continued success also hinged on the public’s acknowledgment of his expertise on sex, youth, and the New Woman. To this end, both husband and wife encouraged the notion—probably true, anyway—that Zelda was the inspiration for many of Scott’s female characters, including Rosalind, Amory Blaine’s devastating crush in

This Side of Paradise.

When asked how long it took him to pen that first novel, Scott answered slyly, “To write it, three months.

2

To conceive it, three minutes. To collect the data in it, all my life”—a clear indication that the characters in the book, including Rosalind, were ripped straight from the pages of Scott’s diary. More directly, in one of his many newspaper interviews on the subject of flappers, Fitzgerald confessed, “I prefer this sort of girl.

3

Indeed, I married the heroine of my stories. I could not be interested in any other sort of woman.”

Zelda drove home the same point when she told a Kentucky newspaper columnist, “I love Scott’s books and heroines.

4

I like the ones that are like me! That’s why I love Rosalind in

This Side of Paradise.…

I like girls like that. I like their courage, their recklessness and spendthriftness. Rosalind was the original American flapper.”

It wasn’t long before people began clamoring for Zelda’s wisdom on the topic of the New Woman. In early 1922, when Scott published his second novel,

The Beautiful and Damned

, Zelda wrote a syndicated review of the book for the

New-York Tribune.

5

Under the title “Friend Husband’s Latest,” she confided that “on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

Zelda wasn’t exaggerating. Scott

had

lifted portions of her letters and diary for some of his work. She was pointing out what many people already assumed: that she was Scott’s artistic muse and, by extension, the first American flapper. She recommended

The Beautiful and Damned

to readers, because “if enough people buy it … there is a platinum ring with a complete circlet” that she had her eye on.

Two years earlier, Fitzgerald had encouraged Max Perkins to incorporate Zelda’s face in the book’s promotional advertisements. “I’m deadly curious to see if Hill’s picture looks like the real ‘Rosalind,’ ” he wrote his editor in January 1920, referring to the sketch artist W. E. Hill contributed to the book’s dust cover.

6

Now, Fitzgerald fretted over the artwork for

The Beautiful and Damned.

“The girl is

excellent of course—it looks somewhat like Zelda,” he told Perkins, “but the man, I suspect, is a sort of debauched edition of me.”

7

In his scrapbooks, Fitzgerald pasted several photographs of Zelda beside the jacket of his new novel. The resemblance was striking.

Positioning Zelda as the inspiration for both Rosalind and Gloria, the lead woman in

The Beautiful and Damned

, was a clever trick.

Rosalind, the earlier flapper character, is a teenager, “one of those girls who need never make the slightest effort to have men fall in love with them,” as Fitzgerald described her. “She is quite unprincipled; her philosophy is

carpe diem

for herself and

laissez-faire

for others.”

8

She revels in her sexual freedom, explaining casually that “there used to be two kinds of kisses. First when girls were kissed and deserted; second, when they were engaged. Now there’s a third kind, where the man is deserted.”

By contrast, Gloria, the central character in

The Beautiful and Damned

, is a different woman altogether. Already in her mid-twenties, she is “Mrs. Anthony Patch,” one of the “younger marrieds” Scott now claimed as his cultural expertise. Newspapers and magazines went along happily with Scott’s redefinition of the New Woman and agreed that “the flapper has grown up in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s latest book.

9

” Acknowledging that a twentysomething wife could still be a flapper if she held to the right attitude, the

Columbus Dispatch

announced that “she is graduated from the bright, trivial, careless atmosphere of flapperdom, and, still wearing all the marks of flapperdom’s charming vulgarity, is borne into an older world made unromantic by the super-sophistication of the people in it.”

Newspapers accepted the notion that Zelda was the original model for both Gloria and Rosalind and noted casually that “Mrs. F. Scott Fitzgerald started the flapper movement in this country.”

10

At Scott’s urging, Zelda slipped ever more assertively into her role as America’s first flapper. During a brief sojourn in St. Paul, he even wrote a musical review,

Midnight Flappers

, for the Junior League’s vaudeville night.

11

Zelda was cast as one of the show’s stars.

To promote Scott’s work—and her own reputation—in mid-1922 Zelda penned a whimsical yet insightful article for

Metropolitan Magazine

on the subject of young American women. Entitled “Eulogy on the Flapper,” her commentary began with a deceptive claim that “the flapper is deceased.”

12

Zelda didn’t mean to suggest that flapperdom was out of fashion. On the contrary: Her article wasn’t really so much a eulogy as it was a declaration of cultural conquest. “Now audacity and earrings and one-piece bathing suits have become fashionable,” she explained, “and the first Flappers are so secure in their positions that their attitude toward themselves is scarcely distinguishable from that of their debutante sisters of ten years ago toward

themselves.

They have won their case. They are blasé.”

Even as she celebrated the flapper for emerging triumphant in the 1920s, Zelda also believed that sexual liberation might ultimately exercise a salutary, domesticating effect on the New Woman. Critics blamed the flapper for a laundry list of social problems—divorce, mental illness, moral debauchery—but Zelda suspected that by “fully airing the desire for unadulterated gaiety, for romances that she knows will not last,” a young, liberated woman might ultimately find herself “more inclined to favor the ‘back to the fireside’ movement than if she were repressed until she gives her those rights that only youth has the right to give.…

“ ‘Out with inhibitions,’ gleefully shouts the Flapper,” Zelda continued, “and elopes with the Arrow-collar boy that she had been thinking, for a week or two, might make a charming breakfast companion. The marriage is annulled by the proverbial irate parent and the Flapper comes home, none the worse for wear, to marry, years later, and live happily ever afterwards.”

Zelda was effectively articulating an argument that would prove increasingly attractive to young women who asserted a right to personal autonomy and pleasure but weren’t ultimately prepared to forsake more conventional dreams of motherhood and monogamous marriage.

On one level, Zelda’s public musings on the flapper were designed, as always, to help turn the wheels of the Fitzgerald family publicity machine. But her “eulogy” also reflected Zelda’s struggle to reconcile her role as a flapper spokeswoman with the realities of her

marriage. With the birth of her daughter, Frances Scott Fitzgerald—known as Scottie—on October 26, 1921, Zelda graduated, at least in principle, from reckless youth to responsible adulthood.

Her article for

Metropolitan Magazine

was a valiant attempt to enlarge the definition of the flapper—to argue that there was nothing really incompatible about being a New Woman and a mother. By throwing off the shackles of Victorian restraint, Zelda claimed, young women like herself had actually prepared themselves to be

better

guardians of home and hearth than their mothers before them. Getting married, having children, becoming an adult—none of these steps necessitated an abandonment of the ethic of self-indulgence that was a staple of flapperdom and a central feature of 1920s culture.

Zelda was a product of this new culture. She belonged to the first generation of Americans who were raised on advertisements and amusements rather than religion and restraint. They rejected many Victorian-era values and redefined the pursuit of pleasure as a noble goal unto itself.

In nineteenth-century white America, men had largely defined their lives, politics, and identities around work. This was a world where a large proportion of citizens owned their own farms or shops. In a country flush with empty territory, even the growing population of wage earners could reasonably aspire to the dream of self-ownership.

When they spoke about the good life, most public authorities in the nineteenth century emphasized asceticism, self-control, and delayed gratification.

13

These values made a great deal of sense in a world populated by independent farmers and shop owners who needed to internalize capitalist discipline. There were tangible rewards for self-control—not just in the next world, but in this one.

By the early twentieth century, the nature of work had changed, and the old, rock-ribbed values of the nineteenth century no longer made sense.

14

Most men now worked for wages. Looking to expand their economies of scale, business owners turned to new forms of scientific management to speed up and increase production, and this meant the deskilling of work. In this environment, the typical worker found his or her job ever more monotonous and unfulfilling. It was a

new world in which there was simply no evident reward for sobriety and asceticism.

Instead, many Americans began to define themselves not through their jobs, but by turning to other outlets like leisure and consumption. This required the creation of a new ethic, one that legitimated rather than scorned the pursuit of pleasure.