Flapper (11 page)

Authors: Joshua Zeitz

American businessmen and industrialists were happy to oblige. In the late nineteenth century, they had perfected new means of output and distribution and could now produce an enormous volume of glassware, jewelry, clothing, household items, and durable goods. But in order to

sell

these items, they needed to persuade a nation raised on the values of thrift and self-denial to complete a 180-degree turn and embrace the principles of pleasure and self-fulfillment.

In this new era, the apostles of good living were no longer ministers and schoolmasters, but advertising executives and public relations professionals who saturated American newspapers, magazines, movie theaters, and radio stations with a new gospel of indulgence. As an adman coolly explained, “The happiness of the [consumer] should be the real topic of every advertisement.”

15

“Sell them their dreams,” urged an advertising professional.

16

“Sell them what they longed for and hoped for and almost despaired of having. Sell them hats by splashing sunlight across them. Sell them dreams—dreams of country clubs and proms and visions of what might happen if only. After all, people don’t buy things to have them.… They buy hope—hope of what your merchandise might do for them.”

Thus, Americans of Zelda Fitzgerald’s generation were raised on a steady diet of bright and glitzy department store windows, advertisements and amusements, consumer products, and magazine articles—all urging them to let go, enjoy life, and seek out personal happiness.

“You find a

Road of Happiness

the day you drive a Buick,” promised a typical 1920s advertisement.

17

“The same old story of the nose to the grindstone,” another ad scolded.

18

“No time for play. No time for anything but work. And no time then to make a success of himself. Always too busy grinding—grinding. A slave to routine work.”

The message was simple: To be a success in the modern world, it was essential to have

fun.

To have fun, you had to buy something.

Zelda Fitzgerald spoke for a generation of Americans who grew up believing that the pursuit of personal happiness was a noble goal. No wonder the motto beneath her high school yearbook picture read:

Why should all life be work, when we all can borrow.

19

Let’s only think of today, and not worry about tomorrow.

And if it was good or even therapeutic to buy a new pair of shoes or a Buick in the pursuit of pleasure, couldn’t the same be said of romance and even sex?

Margaret Sanger, the famous birth control advocate who endured repeated arrests for disseminating information on family planning, made much the same argument when, in the 1920s, she urged women to triumph over “repression” and chase “the greatest possible expression and fulfillment of their desires upon the highest possible plane.”

20

This, she explained, was “one of the great functions of contraceptives.”

Sanger was an erstwhile socialist organizer who had once cavorted with the likes of such radical agitators as Emma Goldman, Mabel Dodge, Alexander Berkman, and “Big Bill” Haywood.

21

When the militant International Workers of the World (IWW)—better known as “Wobblies”—struck the textiles mills at Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912, Sanger had helped evacuate the children of striking unionists. A year later, when the Wobblies called workers out of the mills at Paterson, New Jersey, Sanger had walked the picket line and helped plan a benefit pageant at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Sanger, a fiery propagandist who was a magnet for media attention, pegged her advocacy of family planning to a combination of feminist and socialist commitments. Borrowing—some would say stealing—from Emma Goldman’s speeches on population control, Sanger called on working-class women to undertake a “birth strike” to deprive voracious capitalists of the surplus labor that kept wages pitifully low and working conditions both dangerous and backbreaking.

22

Whereas classical Marxists had urged the proletariat to be fruitful and multiply—all the better to raise an international army of workers who would overthrow capitalism—Sanger and Goldman begged poor women to embrace “voluntary motherhood.” Only by limiting the size of their families would they stop producing “children who will become slaves to feed, fight and toil for the enemy—Capitalism.”

23

By the 1920s, Sanger had switched tacks. After flirting briefly with the eugenicist movement, she came to stress the personal dimension of family planning. By eliminating the threat of unwanted pregnancy, she explained, birth control would help women to realize their “love demands” and “elevate sex into another sphere, whereby it may subserve and enhance the possibility of individual and human expression.”

24

Contraception wasn’t “merely a question of population,” she argued on another occasion. “Primarily it is the instrument of liberation and human development.”

25

Margaret Sanger had found the right argument for the times, and certainly she wasn’t the only Jazz Age apostle of self-realization and fulfillment.

In the beginning, Zelda told readers, the flapper “flirted because it was

fun

to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure; she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring.

26

She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do.”

A young woman in Columbus, Ohio, echoed this logic when she claimed, “There is no air of ultra smartness surrounding us when we dance the collegiate, smoke cigarettes, and drink something stronger than a claret lemonade.

27

The real enjoyment lies in the thrill we experience in these things.”

If fun was the watchword of the younger generation, so was

choice.

Living in a world that was increasingly dominated by glossy magazine ads for makeup, furniture, and clothing, many Americans began applying the idea of the free market in surprising contexts. A news item dated August 1923 brilliantly captured the tensions that marketplace dogma could inspire. “This little town of Somerset [Pennsylvania] has

been somersaulted into a style class war,” reported

The New York Times

, “with the bobbed hair, lip-stick flappers arrayed on one side and their sisters of long tresses and silkless stockings on the other.”

28

When the local high school PTA convened to endorse a new dress code that would bar silk stockings, short skirts, bobbed hair, and sleeveless dresses, the flapper contingent defiantly broke into the meeting and chanted:

I can show my shoulders

,

I can show my knees

,

I’m a free-born American

,

And can show what I please.

These young, self-styled flappers weren’t trying just to have fun, though fun was surely part of their agenda. They were asserting their right to make personal choices. Some forty years before prominent second-wave feminists declared that the “personal is political,” many ordinary women in the 1920s had come to precisely the same conclusion.

“Personal liberty is a Democratic ideal,” argued a 1920s marriage manual.

29

“It is a woman’s right to have children or not, just as she chooses.” Americans had gone to war to make the world “safe for Democracy.” Now, many seemed to believe that the essence of democracy wasn’t just self-governance, but free choice in every realm of life.

Such was the idea behind the

Chicago Tribune

’s remark that “today’s woman gets what she wants.

30

The vote. Slim sheaths of silk to replace voluminous petticoats. Glassware in sapphire blue or glowing amber. The right to a career. Soap to match her bathroom’s color scheme.”

Here was where the modern culture could prove threatening to the Victorians. The ethos of the consumer market glorified not only self-indulgence and satisfaction, but also personal liberty and choice. It invited relativism in all matters ranging from color schemes and bath soap to religion, politics, sex, and morality. This is precisely what concerned the dean of women at Ohio State University when she complained that the younger generation exalted

“personal liberties and individual rights

to the point that they are beginning to spell lack of self-control and total irresponsibility in the matters of moral obligation to society.”

31

Hers was not a lone voice in the wilderness. As a revolution in morals and manners swept across America in the early 1920s, the forces of reaction gathered in a last-ditch attempt to turn back the clock.

7

S

TRAIGHTEN

O

UT

P

EOPLE

N

OT BY CHANCE

, the enemy of the flapper was often the enemy of change. No group brought this fact into sharper relief than the Ku Klux Klan, which enjoyed a brief but alarming resurgence in the 1920s.

Founded in 1866 by former Confederate officers, the original Ku Klux Klan bathed the southern countryside in blood throughout 1869 and 1870 in a half-successful attempt to roll back the gains African Americans had achieved during the early years of Reconstruction.

1

Under the determined leadership of President Ulysses S. Grant, however, the federal government cracked down hard and drove the Klan out of business. By 1871, it was a relic of history.

Racial progress proved to be short-lived, and by the eve of World War I history was being written by the losers.

2

For several decades, southern Democrats and their defenders had found strong allies in the northern intellectual community. The leading historian of the Civil War era, Columbia University’s William Dunning, was training a generation of scholars to write and teach about Reconstruction as a dark episode in American history, marked by the cruel attempts of northern radicals to impose a harsh and unforgiving peace on the white South and to foist black equality on a proud Confederate nation.

Dunning’s interpretation of Reconstruction was dead wrong, but it was conventional wisdom in the first decades of the twentieth century. It fit well with the country’s diminishing goodwill toward African Americans and its steady embrace of social Darwinism and scientific racism.

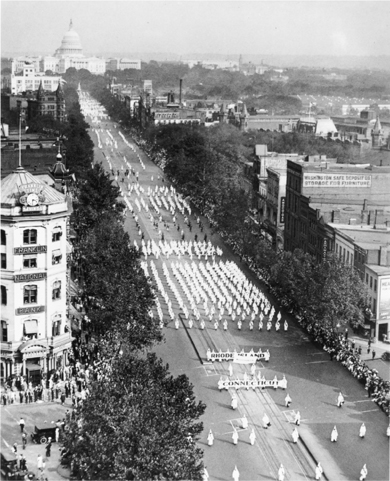

Thousands of Ku Klux Klan members take their protest against the modern age to Washington, D.C., in September 1926.

Even more popular among mainstream readers was a fictional trilogy by the southern writer Thomas Dixon. In

The Leopard’s Spots

(1902),

The Clansman

(1905), and

The Traitor

(1907), Dixon held up the Ku Klux Klan as a savior of white society. The novels became instant best-sellers. Among their admirers was a young filmmaker, David Wark Griffith, who in the years leading up to World War I was laying designs to produce the industry’s first ever feature-length movie.

Griffith needed new material—something stirring, something epic. The romance of the Ku Klux Klan was exactly the right fit. With the author’s blessing, he adapted Dixon’s trilogy into a new screenplay,

The Birth of a Nation.

Released in 1915, the film, which starred the Fitzgeralds’ good friend Lillian Gish, caused a nationwide stir. Millions of viewers lined up to watch almost three hours of melodrama, replete with blackfaced actors portraying black slaves as alternatively dim-witted or predatory. In the climactic scene, white-robed Klansmen gallop into town and save white southern womanhood from the threat of racial miscegenation.

The film was America’s first blockbuster success.

Among its many admirers was a motley group of Georgians who convened on Thanksgiving eve inside the stately lobby of Atlanta’s Piedmont Hotel.

3

They had been electrified by

The Birth of a Nation

and came with the express intention of reinaugurating America’s most notorious and violent fraternity. After gathering together, the group climbed aboard a chartered bus and drove sixteen miles north of the city limits to a magnificent granite peak known locally as Stone Mountain. There, overlooking the distant lights of Atlanta, they fired up a tall wooden cross and set out to replicate the glory of the Invisible Empire. The Klan would ride again.