Flapper (17 page)

Authors: Joshua Zeitz

It wasn’t necessarily hypocritical to press for

equal

voting rights and

special

labor legislation. After all, mainstream suffrage groups

based their demand for enfranchisement on the premise that women were different from men—physically weaker, morally stronger—but nevertheless in need of the vote.

By the 1920s, not all feminists agreed on this point.

On one side of the divide stood so-called social feminists, many of them members of reform groups like the National Women’s Trade Union League, the National Consumer’s League, and the League of Women Voters (the successor to the National American Woman Suffrage Association). Even as they celebrated their achievement of equal voting rights, social feminists continued to argue that women were a more delicate sex, in need of special protective legislation.

This tack didn’t sit well with members of the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Led by the fiery young Quaker activist Alice Paul, the NWP wholly rejected the maternalist argument for women’s enfranchisement and called for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution—a measure that would ban all policy distinctions between men and women.

16

It wasn’t that Alice Paul was totally unsympathetic to working women. “Personally, I do not believe in special protective labor legislation for women,” she said. “It seems to me that protective labor legislation should be enacted for women and men alike … and not along sex lines.” Another member of the NWP warned, “If women can be segregated as a class for special legislation, the same classification can be used for special restrictions along any other line which may, at any time, appeal to the caprice or prejudice of our legislatures.”

17

To the NWP, feminism could not afford to compromise on the

idea

of equality, even if such a position might temporarily set back the cause of working women. If women wanted to share equally in life’s pleasures, they couldn’t claim special immunities from life’s trouble.

Social feminists hit back hard. A member of the League of Women Voters asserted it was obvious that “the most important function of woman in the world is motherhood, that the welfare of the child should be the first consideration, and that because of their maternal functions women should be protected against undue strains.”

18

Many social feminists were middle-class reformers who genuinely felt concerned for “the tired and haggard faces of young waitresses, who

spend seventy hours a week of hard work in exchange for a few dollars to pay for food and clothing.” It was all well and good to invoke abstract doctrines of legal and social equality, but ultimately the ERA wing of the feminist movement would only “free women from the rule of men … to make them greater slaves to the machines of industry.”

19

These issues would take years to resolve. In the meantime, if they could agree on little else, feminists across the divide found most young women in the 1920s sorely lacking in the kind of ideological rigor and political commitment that their own generation of activists had exhibited on such a grand scale. Much as veteran second-wave feminists of the 1990s would lament the seemingly apolitical posture of Gen-X women, flappers simply didn’t strike first-wave feminists in the 1920s as concerned one way or the other about the weightier issues of the day. None of this seemed to augur well for the future of feminism.

When conservatives denounced feminists for betraying a “flapper attitude,” they were missing the point entirely.

20

Most committed feminists were also chagrined by American flapperdom.

There were a few exceptions. Dorothy Dunbar Bromley, a noted liberal writer, defended the “modern young woman” who viewed feminism as “a term of opprobrium.” The problem wasn’t the lipstick-wielding flapper, Bromley wrote, but the “old school of fighting feminists who wore flat heels and had little feminine charm” and their successors—self-styled feminists of the 1920s who “antagonize men with their constant clamor about maiden names, equal rights, women’s place in the world, and many another causes

… ad infinitum.”

Young women weren’t frivolous or apolitical, Bromley argued. They weren’t trading politics for pleasure. Rather, they were “feminists—New Style—truly modern” Americans who “admit that a full life calls for marriage and children” but

“at the same time …

are moved by an inescapable inner compulsion to be individuals in their own right.”

21

The young woman of the 1920s, Bromley concluded, “knows that it is her American, her twentieth-century birthright to emerge from a creature of instinct into a full-fledged

individual

who is capable of

molding her own life.

22

And in this respect she holds that she is becoming man’s equal.”

In condemning the flapper for her turn inward, first-wave feminists may have betrayed a lack of imagination. Perhaps the trick wasn’t to combine the personal and the political. Maybe the personal

was

political. Maybe the flapper was pioneering a distinct brand of individualist feminism.

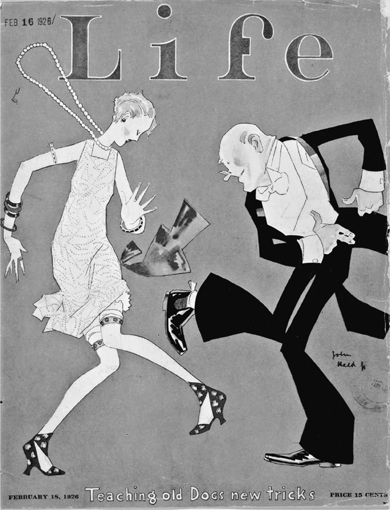

Illustrator John Held Jr. captured the spirit of the Jazz Age.

12

T

HE

L

INGERIE

S

HORTAGE

IN

T

HIS

C

OUNTRY

E

VERYWHERE ONE TURNED

in the mid-1920s, sex was on the brain.

1

When Americans weren’t having it, they were thinking about it or reading about it.

Magazine aficionados consumed real-life glossies like

True Confessions, Telling Tales, True Story

, and

Flapper Experiences

, which ran stories with such lurid titles as “Indolent Kisses” and “The Primitive Lover” (“She wanted a caveman husband”). Dish detergent advertisements featuring scantily dressed Egyptian women guaranteed the “beauty secret of Cleopatra hidden in every cake” of Palmolive. Popular songs of the era included “Hot Lips,” “I Need Lovin’,” and “Nursing Kisses.”

Movie posters for films like

The Cowboy and the Flapper—

“See What Happens When the Cowboy and the Flapper Meet. William Fairbanks and Dorothy Revier do their stuff in a way that raises this picture into the ranks of really dramatic production”—testified to the new level of sexual candor that permeated mass culture.

Though her columns appeared to suggest that Lois Long was dating half the eligible bachelors in Manhattan—and maybe a few of the ineligible ones, too—sometime around 1926 she became romantically involved with the

New Yorker

’s swank but mercurial staff artist, Peter Arno, who pioneered the magazine’s distinctive cartoon humor. He was, as

The New York Times

would later write, “tall, urbane,

impeccably dressed, with the kind of firm-jawed good looks popularized in old Arrow collar ads.”

2

The scion of a prominent New York family (his father was a state supreme court justice), Arno—né Curtis Arnoux Peters—was raised with the best people and attended the best schools (Hotchkiss, Yale). Yet he did everything he could to cast off the shackles of Victorian respectability. At Yale, he dabbled in music and art rather than business or law. Upon graduation, he moved to Greenwich Village rather than the Upper East Side. He changed his name. He changed his friends. But he could never change the way he talked—that upper-crust accent common to Hotchkiss boys—or the way he walked. And he couldn’t change that winning smile.

In many respects, he was a perfect match for Long. He was no prude. In a legendary

New Yorker

moment, Arno penned a cartoon depicting a young couple who appear before a motorcycle cop carrying a removable automobile seat. The caption reads: “We want to report a stolen car.” Harold Ross thought the cartoon was a side splitter and immediately gave it his approval. A week later, when it was already too late to change the edition, he finally got the joke. He took Arno out for a drink a few days after the magazine hit the stands.

“So you put something over on me?” he asked with a forlorn expression. Arno shrugged, sipped his cocktail, and asked why Ross had approved a cartoon he didn’t even understand. “Goddamn, I thought it had a kind of Alice in Wonderland quality,” Ross replied. “It would have had the same effect on me if the guy had been holding a steering wheel instead of the back seat!”

With the exception of Harold Ross, James Thurber quipped, “the cartoon was surely understood by everybody else between the ages of fifteen and seventy-five.”

3

Long and Arno carried on an affair for a year or so before marrying in 1927. Neither courtship nor marriage seemed to have domesticated either partner. Once, they passed out after a long night of drinking at the

New Yorker

’s staff club. The next morning, according to Long, managing editor Ralph Ingersoll found them “stretched out nude on the sofa and Ross closed the place down. I think he was afraid Mrs. White would hear about it. Arno and I may have been married to

one another by then; I can’t remember. Maybe we began drinking and forgot that we were married and had an apartment to go to.”

4

On another occasion, after lending the celebrity couple his town house for the weekend, Harold Ross fired off a terse note to Long. “I just learned that you … copped a lamp from my house that I was going to send back to Wanamaker’s,” he opened.

5

“All right, you can have it—as a bridal gift, with my compliments.”

Especially when clothed, they struck a handsome couple. “She had been a sort of Zelda Fitzgerald figure,” a staff member explained many years later.

6

“She was beautiful and witty and [Arno] was handsome and worldly. They had been … the most glamorous couple in New York.”

Their marriage announcement in the society columns was typically irreverent but also too clever by half, as it effectively blew Lipstick’s cover.

7

“Lois Long, who writes under the name ‘Lipstick,’ married Peter Arno, creator of the Whoops sisters, last Friday,” read the notice. “The bride wore some things the department stores give her from time to time, and Mr. Arno wore whatever remained after his having given all his dirty clothes to a man who posed as a laundry driver last week.… Immediately after the wedding the couple left for 25 West 45

th

Street, where they will spend their honeymoon trying to earn enough money to pay for Mr. Arno’s little automobile.”

Arno had bought the car, a Packard, on the understanding it could reach one hundred miles per hour on the open road.

8

The newlyweds tested it for four thousand miles, couldn’t achieve the promised speed, and sued the automobile company for breach of contract.

No, Lois Long’s lifestyle was anything but ordinary. As she later summed it up, “All we were saying was, ‘Tomorrow we may die, so let’s get drunk and make love.’ ”

9

Most young women simply never lived as wildly and recklessly as she. For starters, though the urban flapper was popularly known to flout the rules of Prohibition, in fact nationwide alcohol consumption plunged in the 1920s.

10

If many young people—particularly city dwellers—found plenty of ways around the law, still, on the whole, the Eighteenth Amendment accomplished just what it set out to do.

What’s more, though about half of all college-educated women in

the 1920s had lost their virginity before the eve of their weddings, most had slept only with their future husbands. To be sure, the younger generation regarded premarital sex and foreplay with a far more liberal eye than their parents. In one study, three-quarters of all college-age men expressed their willingness to marry women with previous sexual experience.

11

But most of these Jazz Age youths viewed sex as an appropriate and fulfilling act between two people who loved each other and intended to marry. Although this was a revolutionary view in its time, it paled in comparison with the further unraveling of social customs in the 1950s and 1960s.

In some ways, the personal feminism of the flapper era even

narrowed

the romantic and sexual possibilities available to women.

In the Victorian era, before the latter-day revolution in courtship and dating, women and men had inhabited a world largely segregated by gender. Men worked, women ideally stayed at home. Men socialized at the saloon, the private club, or the fraternal society; women passed their free hours at one another’s homes. In an environment where men and women rarely enjoyed meaningful relationships outside of their families, many women—especially middle-class teenagers who attended finishing schools and colleges—developed intense emotional and physical bonds with one another.