Flapper (37 page)

Authors: Joshua Zeitz

But Louise’s reputation quickly caught up with her. Before long, Frank Case, the owner-manager, cornered her as she walked out of the elevator.

“How old are you, Miss Brooks?”

14

he asked.

“Seventeen,” Louise replied.

“Are you sure you aren’t fourteen?”

“Yes.”

“Does your family know you are here?”

“Yes.”

“Well, George Cohan”—George M. Cohan, the Broadway musical composer—“just phoned me to tell me last night that he came down the elevator with a fourteen-year-old black-haired girl in a little pink dress. Where were you going at two-o’clock in the morning?”

It didn’t help matters when Louise admitted she had been on her way to Texas Guinan’s El Fay Club. Case didn’t need any trouble in his hotel. He arranged for Louise to move into the Martha Washington, “a respectable women’s hotel on East Twenty-ninth Street.”

Louise rebounded. She was an exceptional dancer, and she knew a lot of famous and influential New Yorkers. Late fall found her appearing in

George White’s Scandals

, the great rival act to the

Ziegfeld Follies

and the very same show that saw a hopelessly inebriated Scott Fitzgerald strip off his clothes along with the professional performers back in 1920 or 1921.

Less stuffy and a little more risqué than the

Follies—

in many numbers,

the dancers appeared almost completely nude—the

Scandals

was quick to incorporate into its acts the latest dance crazes sweeping black Harlem and white collegiate America. And Louise excelled like no other dancer at the Charleston, a Harlem import that dominated the Broadway stage in 1923 and 1924.

Restless as always, Louise quit the

Scandals

in 1924, spent a few weeks in London, where she danced in local cabaret performances, and returned, dead broke, to New York, where Florenz Ziegfeld was happy to hire her for the 1925 run of his

Follies.

Life was pretty good as a

Follies

girl.

15

The pay wasn’t bad—normally between $250 and $300 per week (Louise would have been on the higher end of the scale), equivalent to an annual salary of about $150,000 in today’s money. There were also plenty of ways to line one’s pockets with still more money. “There was a hand-picked group of beautiful girls who were invited to parties given for great men in finance and government,” she later explained to a correspondent. “We had to be fairly well bred and of absolute integrity—never endangering the great men with threats of publicity or blackmail. At these parties we were not required, like common whores, to go to bed with any man who asked us, but if we did the profits were great. Money, jewels, mink coats, a film job—name it.”

It was an extraordinary lifestyle, quite unlike that led by most American women. Or was it? Though Louise Brooks dined at the best restaurants, wore the best clothes, went to the best shows, and associated with the best people, the delicate art she practiced every day—the unspoken exchange of sex and romance for material satisfaction and financial security—was being lived out on a lesser scale by millions of underpaid shopgirls, garment workers, and office secretaries whose every date to Coney Island or to the movie theater was fraught with subtext and negotiation.

Yet unlike those other women, Louise Brooks was plunged deep into the excess and affluence of the fabled 1920s. By mid-1925, she was newly installed in a plush apartment-hotel at 270 Park Avenue and was a regular at Texas Guinan’s nightclubs, where adoring fans beseeched her to take the stage and dance the Charleston.

That same year, she entered into a summer affair with Charlie

Chaplin—arguably the most famous Hollywood figure of his time and certainly one of the most famous personalities of the age—who was in town for the premiere of his new film,

The Gold Rush.

Louise was eighteen; Chaplin was thirty-six. They spent weeks together, trolling the nightclubs until daybreak, sleeping until noon, and taking long walks—sometimes for hours—through Central Park and in downtown Manhattan. They also indulged each other’s boundless sexual appetites.

16

Over one weekend, Brooks and Chaplin disappeared into a hotel suite with their friends A. C. Blumenthal, a film financier, and Peggy Fears, a close companion and fellow Ziegfeld girl. They didn’t emerge until Monday. Years later, Louise admitted to a friend that the foursome spent most of the forty-eight hours in a state of undress and complex sexual entanglement.

If someone had bothered to call Louise Brooks a flapper, she would have shrugged off the charge (or compliment). “The flapper,” she wrote years later to her brother, “did not exist at all except in Scott Fitzgerald’s mind and the antics he planted in his mad wife Zelda’s mind.”

17

As for Louise, she was just living her life the way she knew how. She wasn’t trying to be a flapper. She had, in fact, been wearing her hair bobbed since the age of nine or ten. But Hollywood had a different idea.

One of Louise’s occasional paramours in 1925 was Walter Wanger, a producer for Paramount Pictures who persuaded her to do some motion picture work. Famous Players-Lasky, the studio that formed Paramount’s core, was still headquartered in Astoria, Queens, so Louise could easily shoot scenes during the day and make it back to Manhattan by dusk to perform in the

Follies.

Her debut screen performance,

The Street of Forgotten Men

, was so strong that it soon earned her competing offers of a five-year contract from Warner Brothers and Paramount, both of which were in bad need of a flapper starlet to compete with the likes of First National’s Colleen Moore. (Clara Bow hadn’t yet moved over to Paramount.) Louise wasn’t particularly interested in the movies, but she was restless, and the money was good ($250 per week to start, rising to $750 per week by the end of the decade), and she figured she could still do some stage work.

Wanger told her to sign with Warner Brothers; their relationship was an open secret, and he didn’t want her career or reputation to suffer from the whisperings of jealous rivals and gossipmongers. Louise ignored the advice and went with Paramount. Over the next two years, she churned out a series of box office flapper hits like

Love ’Em and Leave ’Em

, a comic exposé of “modern youth’s system of loving,” as the studio ads billed it. Brook’s character, a department store salesgirl named Janie Walsh (“like the crazy flapper you fell for last year,” Paramount promised viewers), steals her sister’s boyfriend, gets in way over her head at the racetrack, and, for good measure, tries to make off with the Employees’ Welfare League fund to pay off her gambling debts. The opening scene finds her luxuriating in bed, her jet black bob mussed and her negligee revealing more than just a little skin. It was easy for Louise to play the role. She was the real thing.

When Louise wasn’t on the set, she could sometimes be found at William Randolph Hearst’s vast, rambling estate, San Simeon, where the famous newspaper magnate lived with his mistress, actress Marion Davies.

18

There was nothing quite like it. Acres of well-manicured grounds surrounded an enormous main castle, three guest villas, swimming pools, tennis courts, a working cattle ranch, horse stables, and a variety of wonderland attractions. Though theoretically a guest of Marion Davies’s, Louise was really a favorite of the self-styled Young Degenerates—a motley group of teenagers and twentysomethings anchored by Pepi Lederer, Davies’s seventeen-year-old niece. Pepi lived off Hearst’s generosity and dedicated most of her time to liquor, women (she was unapologetically gay in an era when it was all but impossible to be out of the closet), and cocaine.

Louise wisely stayed away from the cocaine, but she passed weeks on end at San Simeon, drinking from Hearst’s stockpile of expensive champagne, partying with the Degenerates, and working to circumvent the old man’s strictures against hard liquor.

“The most wondrously magnificent room in the castle was the dining hall,” Louise remembered. “I never entered it without a little shiver of delight. High above our heads, just beneath the ceiling, floated rows of many-colored Sienese racing banners dating from the thirteenth century. In the huge Gothic fireplace between the two

entrance doors, a black stone satyr grinned wickedly through the flames rising from logs propped up against his chest. The refractory table seated forty. Marion and Mr. Hearst sat facing each other in the mottle of the table, with their most important guests seated on either side.” Louise was normally relegated to “the bottom of the table, where [Pepi] ruled.…

“At noon one day,” Louise remembered, “before Marion and Mr. Hearst were onstage, we were swimming in the pool when Pepi learned that a group of Hearst editors solemnly outfitted in dark business suits, was sitting at the table, loaded with bottles of scotch and gin, in the dining room of the Casa del Mar—the second-largest of the three villas surrounding the castle. Pepi organized a chain dance. Ten beautiful girls in wet bathing suits danced round the editors’ table, grabbed a bottle here and there and exited.” One of the stunned newspapermen turned to another and asked, “Does Mr. Hearst know these people are here?”

Louise had slept with women before, but usually in the context of group sex. For good measure, she slept with Pepi. Later in life she’d claim to have had little interest in women, but she never held to a hard and fast rule. Rumor held that she had even had a one-night stand with Greta Garbo. Privately, Louise acknowledged it was true.

If a dangerous flapper was what Paramount wanted, a dangerous flapper was what it got. The studio was pushing the envelope, and it had found just the right woman to play the part.

24

T

HE

D

REAMER

’

S

D

REAM

C

OME

T

RUE

W

RITING SHORTLY AFTER

the halcyon days of the 1920s, novelist Nathaniel West captured brilliantly the central place that Hollywood occupied in the American imagination. “All their lives they had slaved at some kind of dull, heavy labor,” he observed of his nameless countrymen, “behind desks and counters, in the fields and at tedious machines of all sorts, saving their pennies and dreaming of the leisure that would be theirs when they had enough.

1

Finally, the day came … where else should they go, but to California, land of sunshine and oranges.”

People who came of age in the 1920s knew exactly what he meant. Hollywood—ostensibly just an incorporated district of Los Angeles—had come to represent the apotheosis of American plenty. “No romance has ever unfolded on the silver screen,” boasted a Jazz Age author, “no fantastic tale from the pen of Jules Verne has ever depicted the glamorous drama of Hollywood, America’s real, live Fairyland—the dreamer’s dream come true.

2

Brilliant as the eternal California sunshine, soft and languid as the California moon, the beauty of Hollywood is the glorious envy of the artist, the never-to-be-obtained goal of the poet.”

Originally headquartered in cold, windy, snow-blown New York City, the movie barons flocked en masse to California just after World War I in pursuit of a virgin setting where labor was cheap, land abundant, and the vista unspoiled by industrial blight and decay. By the 1920s, Hollywood—the Los Angeles neighborhood so many of them staked out as home—had “become the Enchanted City.”

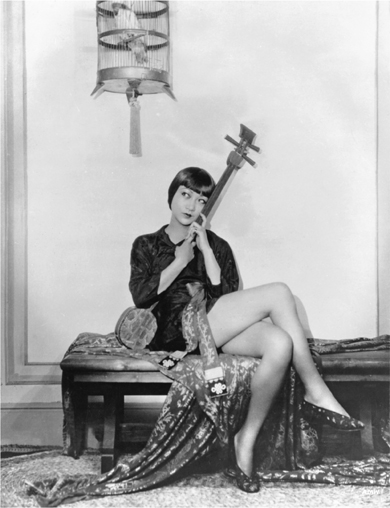

Chinese American actress Anna May Wong challenged the popular belief that flappers need be white and native-born.

“Mohammadans have their Mecca,” a writer observed, “Communists have their Moscow, and movie fans have their Hollywood.”

Forget for a moment that the moguls chose Los Angeles mainly for pragmatic reasons—its extreme hostility to organized labor, its lower tax rates, the extra hours of sun for outdoor shooting, and its proximity to desert, ocean, and mountain panoramas. To millions of readers of fan magazines and faithful attendees of Saturday matinees, Hollywood represented the twin dreams of abundance realized and self-reinvention achieved.

“In the strange place which is Hollywood,” observed a writer for

Motion Picture Classic

in 1927, “ … when success does come, it comes swiftly and almost without effort.

3

Youngsters, without any preparation, receive immense contracts for a trick of smiling, a tilt of nose, the curve of cheek.”

Everyone was there, even Scott Fitzgerald, who took an unsuccessful stab at writing for the movies. In 1927, he contracted with United Artists to write a new flapper film. The end result was weak. Set, as always, in Princeton,

Lipstick

was the story of a young girl who is unjustly held captive but then discovers a magic tube of lipstick that makes every boy want to kiss her. The studio executives were unimpressed. Scott’s film was never produced, and he had to settle for his $3,500 advance rather than the full $16,000 payment provided for in his contract. In Hollywood, either you had it or you didn’t. Scott didn’t.