Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (29 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

One might reasonably think, Well, if any of those women actually knew what was in it, they’d stop taking it, wouldn’t they? But in (creepy) fact, even that unsavory piece of information probably wouldn’t make any difference at all, and the reason is simple.

We women fear aging. All people do, but it’s worse for women, even worse for American women, and even worse still, at least according to one study, if one is straight rather than gay. As smart and tough and accomplished a cookie as she might be, the average woman is trained from the moment she turns thirty to start dreading those telltale signs: the chin swags, the odd hair growing out of a mole, the crow’s-feet, the thickening waist, the thinning hair.

And many of us are terrified of menopause. We fear becoming a lampoonable cartoon of a woman with ludicrous symptoms: hot flashes, temper tantrums, night sweats. We dread turning into a lumpish, sexless gnome in a pastel sweatsuit, existing solely for the free cheese samples at the supermarket and owning too many mugs with funny sayings on them. And even if we don’t have a maternal bone in our body, we brood endlessly about the last gasp of fertility, the end of our “usefulness” as women.

But where does this unholy terror come from? Good question, we reply … and suggest, as is so often the case when it comes to menstruation, that we take a good look back through the annals of history for a possible explanation.

For centuries, menopause wasn’t seen as a natural function, but instead as something gone seriously wrong, an actual disease. It’s important to remember that before the twentieth century, just the idea of women routinely living a third of their lives after menopause was beyond freakish. Today, while the age of menopause hasn’t changed, life expectancy for the average American woman has ballooned: from forty-nine in 1900 to nearly eighty-one in 2007. As a result, there are close to fifty million midlife women living in the United States today. Yet until quite recently in world history, a woman living past her childbearing years was like a total eclipse of the sun, a rare anomaly to be viewed with suspicion, even fear.

In the Middle Ages, witchcraft was considered a reasonable explanation for the sudden stoppage of blood. Even before that, women who stopped menstruating were assumed to be out of balance somehow. From the 1921 book Menstruation and Its Disorders: “By the old school of humoral pathologists, the cessation of menstruation was looked upon as a matter of serious consequence, often causing serious disorders and calling for the operation of blood-letting. Perhaps these old observers are in part responsible for the great dread with which the menopause is even now looked forward to by a large proportion of womankind.”

This, of course, was a not-so-veiled reference to Hippocrates and his wacky but popular “humorism” theory. As bloodletting mimicked menstruation, it was thus considered a cure for the disease of menopause. Leeches were routinely applied to a woman’s back, neck, and genitalia—all to get that stagnating, diseased blood out.

It took the original Freudian, Sigmund himself, to arguably move the entire discussion about menopause one eensy-weensy baby step forward by deciding it was a neurotic condition rather than a clinical disease. In his opinion, menopausal women were “quarrelsome, peevish, and argumentative, petty and miserly.” He heartily recommended the liberal use of drugs, namely sedatives, to keep menopausal women calm and collected.

Thanks to Freud, equating menopause with mental illness became a given. Yet even insanity wasn’t considered the worst part about menopause. On a planet where for thousands of years, even today, a woman’s worth has been judged exclusively by the productivity of her womb, what the hell was the point of a barren woman, anyway? What’s more, the menopausal female was no longer considered any good for sex, either. In 1913, T. W. Shannon, the author of Self Knowledge, wrote that a husband “should have no sexual relations during the change of life in his wife. If the husband wishes to protect the health of his wife and himself, prolong their lives, increase their usefulness and happiness he must bring himself to complete self-control”; and what’s more, that sex during menopause was both unsanitary and unhygienic, as it would most likely cause the buzz kill known as “flooding,” a veritable deluge of menstrual blood.

All this talk about sexual relations was, of course, assuming a man even wanted to get anywhere near his perimenopausal wife. Even this was questionable, especially if he was unfortunate to have read such descriptions of her decay in the 1954 Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex: “The layer of fat in the region of the mons veneris and in the large lips of the vulva starts to shrink. The vulva becomes smaller and flabbier, the small lips become withered and change into thin folds. The fatty glands, formerly present in more than adequate amounts, disappear almost completely, so that there are only remnants of them left.”

Similarly, Emil Novak, in his 1921 book, Menstruation and Its Disorders, dutifully reports that “the vulva loses its velvety vascular appearance and becomes thin, pale, and transparent looking, giving the surface a rather pasty appearance,” and makes sure to mention that pubic hair becomes “gray and straggly.” Helpfully contributing to the positive tone, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex describes in detail how the loss of skin’s elasticity keeps it from being able to hold fat deposits in place, so that the womanly curves men find so attractive “literally slide down, and that, in particular, the cheeks, throat, breasts, abdomen, hips and buttocks become flabby, distorting the body.”

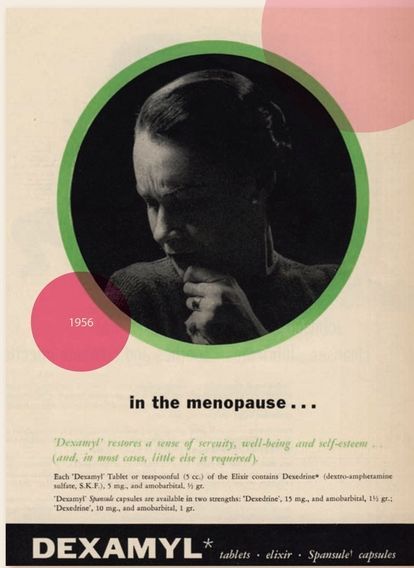

Smith, Kline & French

It’s true that in a time when women had nothing, really, except their families, the loss of fertility plus their grown children’s independence often combined to create emotional stress and a sense of worthlessness that peaked just as menopause was starting. The resulting combination was probably enough to make any reasonable female seem neurotic, depressed, even a little unhinged on occasion.

There was in addition the genuine fear that menopause could cause serious disease. Hippocrates himself wrote that menopausal women “are frequently affected with the itch, the elephantiasis, boils, erysipelatous disorders, or scirrhous cancerous disease.”

Don’t let the fancy-pants, old Greek medical language throw you. He was, in fact, talking about cancer. Considering that abnormal bleeding is a known symptom of uterine cancer, dramatic menstrual changes probably convinced many women in years past they were at death’s door. No wonder countless women dreaded getting older and the terrifying physical, emotional, sexual, and social changes that went along with it.

Yet is the end of menstruation really that awful? So bad that today, we’ve been reduced to quaffing en masse what sounds like a witch’s brew of horse pee in a frantic attempt to stave off the inevitable? What exactly is menopause, anyway?

First off, menopause is actually something that isn’t: namely, it’s the absence of menstrual flow for twelve consecutive months. The seemingly endless changes leading up to it, with all of those familiar symptoms, aren’t actually menopause at all, but perimenopause (“peri” meaning “around” or “near”), and that can last for up to fifteen years. Out of an average reproductive life of thirty-seven years or so, perimenopause can comprise quite a significant chunk.

No one’s quite sure exactly what kicks off the entire process, and while the average age is fifty-one, all kinds of factors (smoking, drinking, radiation treatment or chemotherapy, removal of the ovaries and/or uterus, family history) can bring about an earlier start. On the other hand, women who are heavier, married, or have never had children seem to start somewhat later, as do women who suffer from uterine fibroids.

Perimenopause can often begin in one’s thirties and be the silent, undiagnosed reason for all kinds of annoying physical and emotional changes going on. The process can take such a long time, women and their health-care providers often miss the most obvious (or not so obvious) explanation: that it’s actually hormonal shifts that are causing all those mysterious headaches, backaches, sleep problems, skin eruptions, and mood swings.

Menopause isn’t directly related to menarche. Nevertheless, many women ruefully call it menarche in reverse, as it’s a similar gradual shift in hormones, albeit in the opposite direction, and one often fraught with similar physical and emotional turmoil, as well. In fact, many of the symptoms are eerily similar to what we went through as adolescents, during our early days of menstruation. What adult woman ever thinks she’ll have to deal with irregular cycles, unexpected leaks, acne breakouts, and off-the-wall mood swings all over again?

Most women go through menopause in their late forties or early fifties. Still others stop menstruating permanently in their thirties or even twenties, in which case it’s known as premature menopause or premature ovarian failure. Younger women then have to grapple with the fact that their ability to reproduce is gone, often before they’ve had time to have children or even decide whether they wanted any. They also suffer an increased risk for heart disease and osteoporosis, against which estrogen acts as effective protection.

Menopause doesn’t refer to the years after your period ends. Once those twelve period-free months have passed, you’re technically postmenopausal. It’s not a disease, nor is it the end of your life, not by a long shot. Given current longevity rates, the average postmenopausal woman can look forward to a good thirty years of life left … which, funnily enough, is just about as long as she was menstrual in the first place. It’s a natural and inevitable process that will, most assuredly, happen to any woman at some point or another. Yet from all the hubbub surrounding the subject, menopause has apparently morphed into something practically worse than death itself. The medical and pharmaceutical companies share more than part of the blame, continuing to encourage our fears by pushing treatments that have often proved to be more questionable, dangerous, or nauseating than previously realized.

During perimenopause, the reproductive system gradually shuts down. Ovaries stop responding to stimulating hormones sent from the brain, which leads to diminished egg maturation. This leads to decreased estrogen and progesterone production, which eventually throws the entire reproductive system into a mild tizzy. While the process is natural and actually relatively simple, it can feel like the most confusing, out-of-control, and basically endless process one’s body has ever gone through.

One of the first signs of perimenopause is irregular periods. Regardless of how much of a Swiss clock one’s ovaries may have been for much of one’s adult life, one may suddenly find oneself back in eighth grade, when cycles came and went at will, with unexpected torrents of blood coming out of nowhere, alternating with mere dribbles. For some perimenopausal women, cycles slow down and periods come further and further apart, even skipping a month or two altogether. For others, the reverse is true: as the ovaries stop releasing eggs and the accompanying hormones aren’t secreted, the increasingly insistent pituitary gland sends out more and more stimulating hormones, trying to jump-start the cycle. Ovulation happens earlier, the whole cycle speeds up, and pretty soon, it may seem as if the second one damn period ends, another starts up almost immediately.

Clots and bleeding for fifteen days, bleed through two super-plus tampons, and a pad at night, only to wake up in bloody sheets or bleed through clothes at work, never knowing when it’s coming.

—Jennifer B.(47)

Some women experience far lighter flow, others much heavier, and some women have periods that are so unnervingly intense, there’s actual clotting involved. The four-day average is thrown out the window like last week’s lunch: perimenopausal periods can last anywhere from a couple of days to a couple of weeks. Heavy periods can be brought on by excessive uterine buildup due to lowered progesterone levels. They can also be caused by fibroids, suffered by 40 percent of all perimenopausal women. And even though such symptoms usually go away by themselves after menopause, that can be cold comfort to many women.

Hands down, the superstar of perimenopausal symptoms, the one that literally needs no introduction, is the hot flash: the intense, pizza-oven-esque heat that usually starts in the waist or chest and rapidly zooms up to the neck, face, and scalp. That internal inferno promptly unleashes a veritable blouse-soaking, hair-drenching sweat storm, as the body desperately tries to cool down … and that, in turn, leads to severe, all-over chills.

Not all women experience hot flashes, and even the ones who do have their own patterns. Hot flashes vary in intensity, frequency, and duration from person to person. Some women have dozens a day for years, while others have no more than a handful, total. Some hot flashes last for a few seconds, whereas others can go on for half an hour; the average is three to six minutes, although to some women, it can feel like an eternity.

Hot flashes aren’t just an annoying way to ruin a silk blouse. They can also bring on nausea, dizziness, rapid heartbeat, and breathlessness, plus feelings of anxiety and suffocation. For one woman, hot flashes are a mild inconvenience; yet another