Following the Water

Read Following the Water Online

Authors: David M. Carroll

A Hydromancer's Notebook

David M. Carroll

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Boston New York

2009

Copyright © 2009 by David M. Carroll

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carroll, David M.

Following the water : a hydromancer's notebook / David M. Carroll.

p. cm.

ISBN

978-0-547-06964-7

1. Wetland ecologyâNew Hampshire. 2. Wetlandsâ

New Hampshire. 3. Natural historyâNew Hampshire.

4. Carroll, David M.âHomes and haunts.

I

. Title.

QH

105.

N

4

C

267 2009

577.6809742'72âdc22

2008052951

Book design by Lisa Diercks

Typeset in Monotype Fournier

Printed in the United States of America

DOC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Several chapters of this book appeared, in somewhat different form, in

Tufts

Magazine

(Winter 2007) under the title "Scenes from the End of a Season."

Lines from "Villa at the Foot of Mount Chungnan" by Wang Wei, from

Anthology of Chinese Poetry,

edited by Wai-Lim Yip. Copyright ©

1997

by Duke

University Press. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. Lines

from "Escondido en los muros" by Luis Cernuda, from

The Poetry of Luis

Cernuda: Order in a World of Chaos,

by Neil Charles McKinlay (London: Tamesis,

1999). Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSFor Meredith, Harry, and Jim

I

HAVE DEDICATED

this book to three people who have played vital roles in the books I have developed over the past twenty-one years.

Meredith Bernstein, my literary agent, has been there since the beginningâsince before the beginning, in fact, as she was bringing my work to the attention of publishers over the course of eight years before I received my first contract. Between that volume and this one, she has been a steadfast supporter of my writing and art, an unflagging appreciator and believer, and an invaluable ally in getting my books into print.

Harry Foster was my editor for

Swampwalker's Journal

and

Self-Portrait with Turtles

and the driving force behind my writing the latter. Only two books, but they spanned a decade and entailed many drafts, so many pages and, it seemed (to him, I am sure), countless words. I benefited greatly from the dynamic he brought to that unique, complex, and I believe necessary author-editor relationship. Beyond that he was a great personal friend and a champion of my writing. His untimely death at age sixty-two was a deep loss not only for me but for many writers, and for the literature of natural history itself.

Jim Mitchell, Herr Buchhändler, as I called him, was a valued friend and constant personal connection, the source of a remarkable sharing of so many aspects of my work and lifeâmy "book wars" in particularâfor a decade, until his untimely death at age fifty-eight, as I was completing this book. Jim's bookstore in Warner (my "downtown office") and his open, always perceptive conversation and easy, abundant humor provided a venue for me that I will not find elsewhere.

I am indebted to Deanne Urmy for her sensitive and sustained focus, deft touch, and insightful editing of my manuscript. I am fortunate in again having Martha Kennedy as my jacket designer; my drawings could not be in better hands. Peg Anderson's thorough, thoughtful copyediting once again provided critical guidance. My "in-house editor," Laurette Carroll, proved (as she has with my previous books) a crucial touchstone as I worked my way to this final incarnation of a book that goes back some fifteen years in preliminary drafts and drawings, and even deeper in time as something I wanted to write. Rebecca Carroll was a most helpful sounding board from her perspectives as both writer

and editor; she and Barbara Proper offered encouraging comments on aspects of this text as it evolved.

It would have been impossible for meâstill essentially Papyrusmanâto have negotiated the e-world dimensions of completing and transmitting my manuscript for this book without the patient, generous assistance of Ken Young. Brian Butler and Annie Burke served once again as constants in the grounding that has been elemental to all of my published work.

A MacArthur Foundation Fellowship was enormously helpful in clearing the way to completion of this long-contemplated project.

Yearbreak

[>]

Writing April

[>]

A Breath at Thaw

[>]

Return to the Wood-Turtle Stream

[>]

In Memory Only

[>]

Following the Water

[>]

A Day in the Shadow of a Pine

[>]

Transformation

[>]

Gray Treefrogs

[>]

Interval with Red Deer

[>]

Night, Distant Lightning

[>]

Medicine-Smelling Earth

[>]

With the Gray Fox

[>]

Variable Dancer

[>]

Walk to the Floodplain

[>]

A Drink Along the Way

[>]

Dancing Tree

[>]

Hawk-Strike

[>]

Brook Trout, Wood Turtle

[>]

Wading Alder Brook

[>]

Oxbow Meander

[>]

Fallen Buck

[>]

Broken Glass

[>]

Boundary Marker

[>]

YEARBREAKIf there is magic on this planet,

it is contained in water.âLoren Eiseley

A

T THE EARLIEST

openings of the ice in the overwintering niches of the spotted turtles, as minute glimmers of quickening water appear in acres of wetlands still locked in ice and snow, I forsake my winter paths: the worn floor by the kitchen table and fireplace; the even more worn threshold of the narrow doorway to the Oriental-carpeted passage down the back hall, the narrow gallery hung with paintings and drawings above agreeably overburdened bookcases, lined along the floor with stacks of more books and empty frames; the footworn stair treads up to my studio workrooms, with their slender passageways among bookcases, drawing and writing tables, and shelves, all impossibly piled

with papers, notebooks, pencils, pens, and paintbrushes. With the opening up of the earth and water I go beyond my few, close-to-home outer trails of the cold season: my way to the woodshed, as trodden as an ancient deer path, and my modest snowshoe circlings through the back field and bordering woods. At thaw I begin to walk a wider way again, beyond house and gardens, in places every bit as home to me as those.

Some of my paths are of my own making, many are borrowed from deer and muskrat; most are routes that water traces. In some of these water-and-mud channels my feet drop into hollows exactly matching my strides: my own footprints of previous years' passings. In rare places left alone enough, generations of black bears walk historic migration routes in the impressed footprints of their ancestors.

Stepping from a snow-crested bank, I descend into the icy running of the brook. There is the daybreak that comes with every rising of the sun, and there is the yearbreak that comes with thaw and the unlocking of the ice. As I enter the newly opened water, I enter the year and, in a mingling of dream clearly remembered and new dream just beginning, start to wade again the streaming of its seasons.

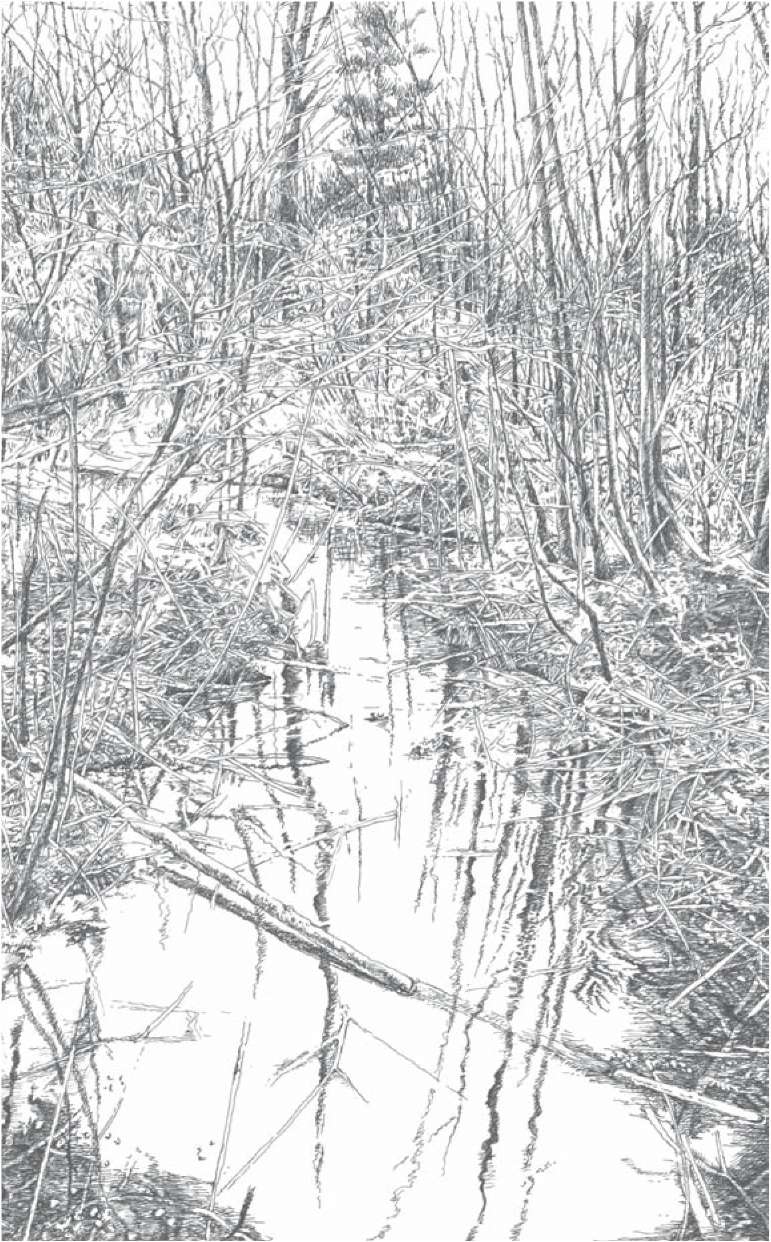

The turbulent whitewater spates of mid-March have run their course. Floods may be brought surging back to life by April rains and the last of the snowmelt from headwater hills, escaping the banks again and surging through the low

white pine terrace, the alder and meadowsweet thickets, the red maple swamp. But for now the brook has settled back within its channel and is not so restless that I cannot see into it. Insulated by neoprene, I wade in. For the first time in the year I move within the variously black, sky-reflecting, and (where shadows allow my sight to penetrate its masking surface) clear, clear flowing of the stream.

At another winter's ending I have one more setting forth, one more initiation. Though I am always one year older, the year is ever new, renascent. I leave the past cold season, a time passed largely in the theater of my own mind, my inner wilderness, leaving it behind like a skin I have sloughed, and enter the wild realm that lies outside of myself and ultimately outside of all human knowing. But my new skin bears the same markings as before, and whatever I encounter within the season extending before me will be at once familiar and completely new.

As I have somehow known from my first intuitive setting out, I will recognize what to follow. The water will set a course and lead me through the days; the days will take me through the year. I go forth directed and open to direction. What guides the feet? the mind? the heart? The heart, too, is forever seeking.

I once brought a naturalist friend, one whose quests range as widely over the planet as mine keep to a circumscribed corner within it, to some of the places that have been at the

heart of what I have followed in the wild over the past three decades. I introduced her to a vernal pool, a marsh, a swamp, a stream, and along the way I found some turtles to show her. I talked some, of what I see, what I look for.

"They say that the Sufi is always looking for his beloved," she said. "You are always seeking your beloved."

My first heading out of the year always takes me back to the first time I wandered out, the beginning of my being there. I felt that I was called, that something called me, and I set out alone. That was in my eighth year, when spring was turning to summer. In every year following, that feeling has come at ice melt, when I go out to see the stream at its first running clear, see the water in marshes and swamps at the moment of opening up, trembling with the restless stirrings of the air at the time of great transitionâwater set free, vibrant and vibrating, shimmering back to the sun, the heart-melting light of spring's awakening. The touch of the ascendant sun on ice at length gives birth to water, and water gives life to the year. After winter's silence, countless dialogues begin. I set out to see if the water has come back, always with the hope, mingled with anticipation, of seeing the first turtle. In the renewal of the year I can find again that first turtle, take it in with my eyes, touch it with my fingertips. Could a year begin for me without this? My life has come to be measured in first turtles.

As I wade against the steady, at times insistent, flow, I

think back to my earliest experiences with this liquid mineral, now clear, now silver or amber, gold, black, deep wine red, or tannic tea, so alive and life-sustaining within its fundamentally physical, utterly indifferent nature. Water nurtures beyond the purely physical. As a boy I entered waters that, if not alive themselves, were so filled with light and life that my binding with them was as much metaphysical as physical. These primal immersions took place in small still-water marshes and swamps and running brooks too minimal to serve the prodigiously expanding economic and recreational needs and desires of mankind. These places of my boyhood continued to hold something of the heart of wildness in a landscape being stripped of all original meaning. Not yet subject to human usurpation and engineering, they were the soul of the seasons, the lifeblood of ecologies. They were wild out of all proportion to their scale in the landscape, and they imparted wildness to my boyhood heart and mind, my youthful imagination.

But over time so many of these watery places, even the least of them, were driven into corners, becoming heavily compromised relicts marginalized out of their existential meaning, if not out of existence. These were my baptismal waters. For all that they gave meâthe beauty and the belonging, the intuitive knowledge of something of my place in life, becoming something that I simply could not live withoutâI think sometimes of the heartache, the anger and

despair, that I would have been spared, had that entrance into the water not opened, had I not entered. Their loss is overwhelming. With every passing year, my following of the water has increasingly become a matter of finding water to follow.