Following the Water (16 page)

Read Following the Water Online

Authors: David M. Carroll

A spark of green arrests my eye. No emerald, a splinter from a shattered bottle catches a slant of sunlight. How has broken glass come to lie in a streambed this far from human habitations? The last earthly lights to mark that we were here on this planet, which we have illuminated to the point of fairly glowing in the dark of endless space, may be those cast by broken glass: brilliant sunsparks, bits of moon gleam, faint flickers of starlight, all reflections of the one original light.

A

S I TURN

toward the brook I am stunned by a sign. It is not the kind of sign that I am ever on the lookout for, ever trying to read on the earth, in the water, among the plants. This is a human designation, a small rectangular boundary marker nailed to a tree and bearing the initials of a land trust. I knew this was coming, but I had no way to prepare myself for it. And I knew it would go hard for me, but I am surprised by the depth of my reaction, physical and mental, to this symbol. It is almost enough to turn me back, send me home. What will be regarded by nearly everyone as a conservation victory, a cause for celebration, I can see only as loss and sorrow. I had tried to steer this change in another direction, beyond conservation to preservation.

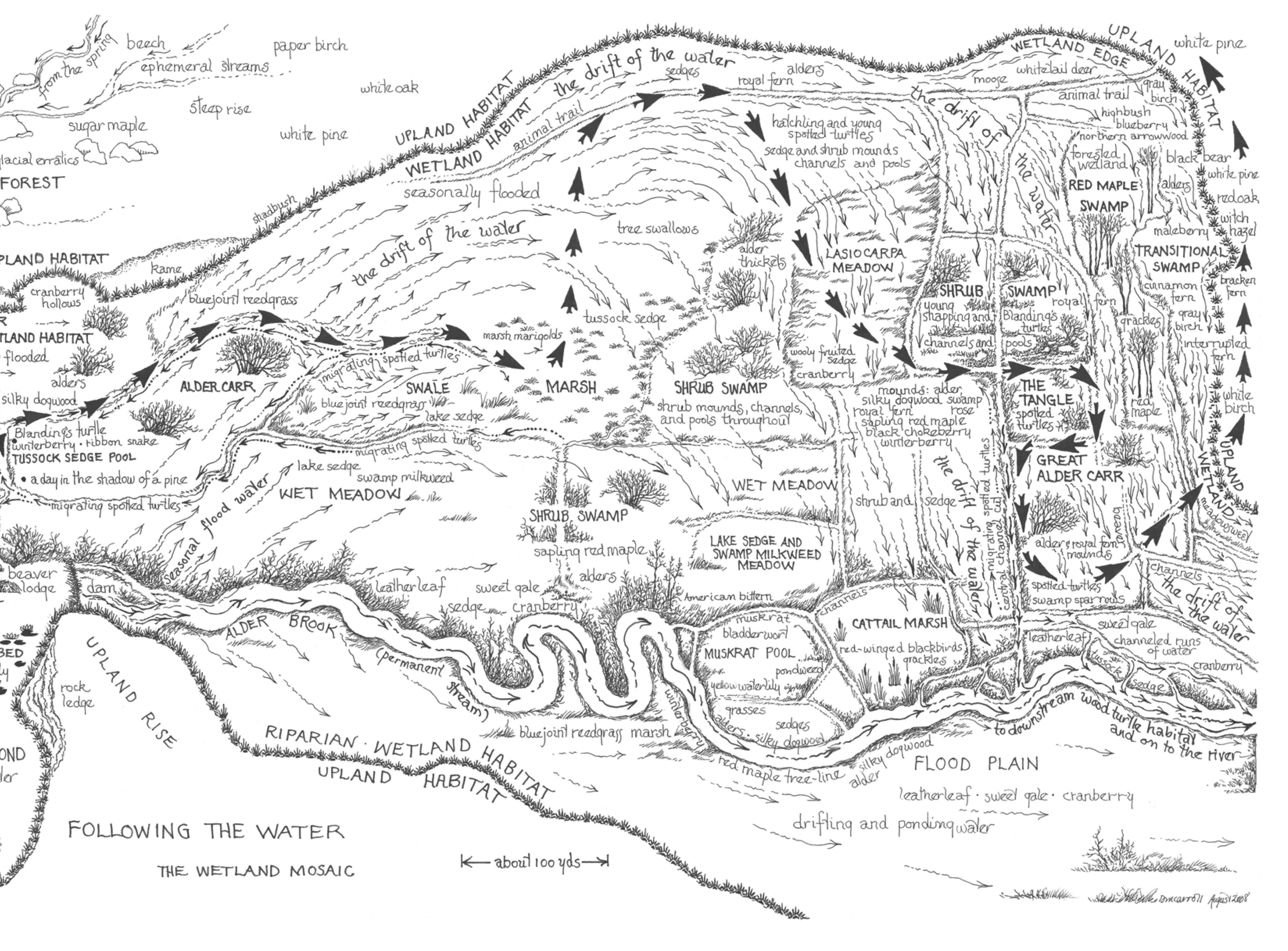

This landscape, an extensive mosaic of contiguous wetland, riparian, and upland elements, all embracing a lingering wildness and extraordinary biodiversity, possesses an ecological integrity that, in the face of the global loss and marginalization of habitats, becomes rarer by the hour. It seemed for a time that it could go differently here, that this place could be exempted even from the intrusion of "passive" recreation, which takes its own toll on wildness and brings pressures to bear on the functioning of a natural ecosystem. But I did see all the familiar signs pointing to this outcome. And now I see that this has become a marked place.

It is all but universally believed that if development rights are bought up and motorized vehicles excluded, if human presence is limited to foot traffic, dogs on leashes, mountain bikes, kayaks, and the like, a parcel of land is saved and its wildlife habitat protected. But in nearly every case, as will be true here, funding sources and the terms of easements mandate a level of access and recreational use that lays the foundation not for true habitat protection but for a playground for people, a human theme park.

A constant refrain of my advocacy for moving beyond stewardship and conservation to preservation is that I do support setting aside places where people can go, from relatively natural areas to city parks. One frequently hears that there are not enough places for people to go. But where

do we not go? We are too many and we tread too heavily. (Perhaps the planet is to blame for being too small.) What tiny percentage of Earth is irrevocably dedicated to providing wildlife sanctuary, to preserving the biodiversity on which, as more people are gradually coming to realize, the health of the planet and, ultimately, of the human condition utterly depends? We cannot seem to allow room for ecosystems to play out their destinies free from human intervention. A room of its own is biodiversity's only requirement.

There is talk of a "nature-deficit disorder," the deleterious physical and emotional consequences of people's alienation from nature. The cure for this, as I have seen it addressed in various forums, tends to be simply getting out of the house and away from electronic pastimes. To this end, state parks are opened free of charge and present games such as "nature hunts" for children, and families are encouraged to provide their young with trampolines in winter and water pistols in summer. The distinction between "outside"âopen spaces and multi-use conservation landsâand true preserves that provide sanctuary for ecologies becomes blurred and is ultimately lost. In this confusion the "natural" that remains in the landscape literally loses more and more ground and, with that, its meaning. It is nature that suffers from nature-deficit disorder.

A relationship, if not an outright union, with nature has

always been and always will be fundamental to the human spirit. But this connection, which has become so profoundly frayed in the modern world, must not be made at nature's expense. Earth cannot be expected toâand in fact simply cannotâbear the weight of a human population approaching seven billion and growing at the rate of some ninety million a year.

I walk past the metal marker and cross the brook. I had a premonition the last time I was out here when I saw a young wood turtle at the edge of a stream bank, in what was likely his final basking of the year, that I might be saying goodbye for more than a winter. I have seen this scenario play out before and have been compelled to move to more remote landscapes. But the world of the turtle species I have known runs out of farther landscapes. I see the clear possibility of my personal history with this wetlandscapeâa long and intimate oneâcoming to an end.

As always, at the close of another season, I look to the thaw beyond the coming winter. I try again to reconcile myself to the fact that the fate of such places is up to the workings of deeper time, nature's own processes. The turtles, and all that they have come to represent for me, will have to endure. Spring will come again, and I will have to find a way to be there. My goodbye has always been until thaw.

As I cross the brook, I see spans of thin ice here and there

on still edgewaters against the bank. This inevitable annual event somehow catches me by surprise every time. It is an undeniable signal of the year's passing. The waters of the fen at the north end of this wetland complex and the marsh beyond it are still open, but featherings of ice have begun to spread over the sphagnum shallows. It is so silent here today. Is it because there are no more insects to sing? The occasional stirrings of a bitingly chill wind are none the warmer for having passed over the glacial pond set in the heart of this wetland expanse. The wind makes no sound in its passing and seems to render the silence all the more striking. In every sense of the word the year is quieting.

I wade into the great alder carr beyond the fen. There is a glazing of ice in the shallows, perfectly clear windows that I am sorry to shatter in my wading. For a time I shatter the silence as well, with sharp, crystalline sounds; then I wade to open water again and the day continues breathlessly still.

The low sun is a white disk in a smoked-glass sky: altostratus translucidus clouds. Ice, poised to march out over the open water in the night, rings the royal fern and alder mounds. I do not know if there will be one more mild spell; it is possible this will be the first and final closing over. The turtles may not move for half a year. If they stir at all, it will be beneath the ice. A couple of calls come from crows over distant pines, and then the profound silence returns.