Following the Water (15 page)

Read Following the Water Online

Authors: David M. Carroll

Water gives life to ten thousand things and does not strive.

It flows in places men reject and so is like the Tao.â

Lao Tzu

W

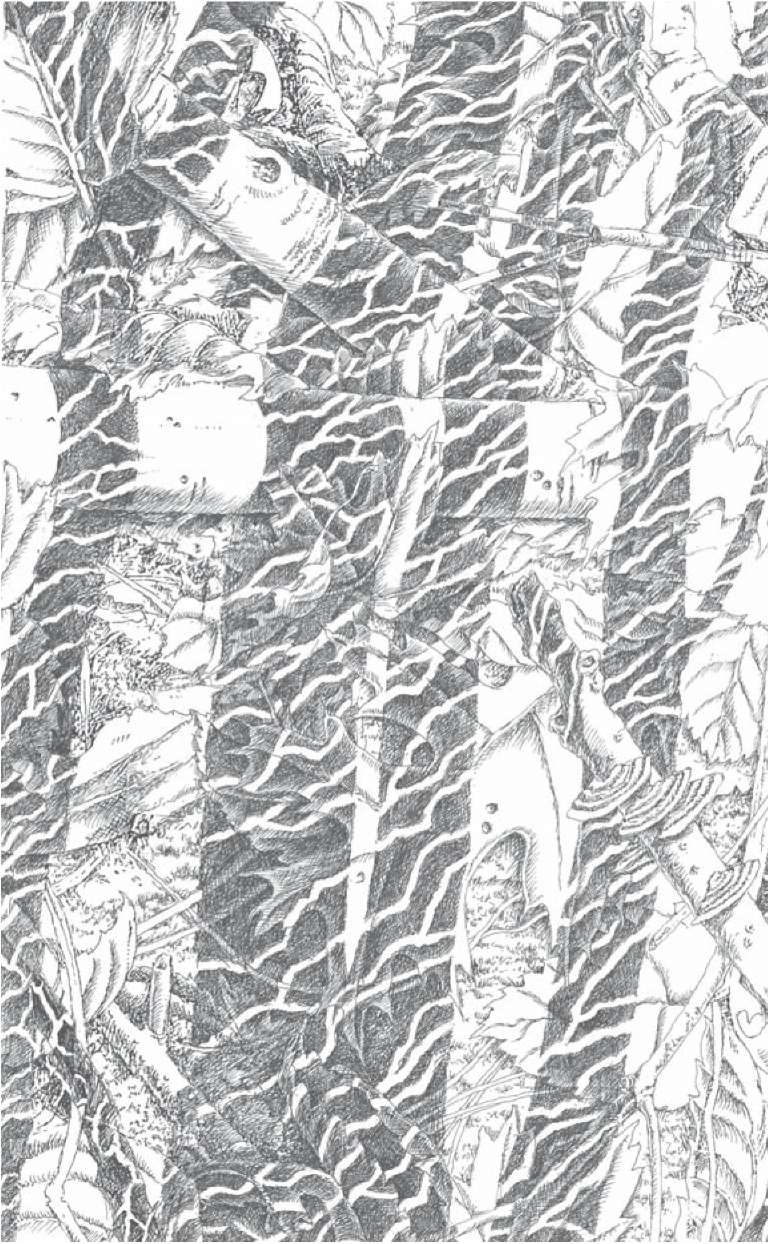

ADING ALDER BROOK,

I search a steep, west-facing bank, just upstream from Willow Dam. The high, nearly perpendicular slope rises twenty feet or so above the brook. At its downstream base beavers built this dam but abandoned it long ago. A tenacious line of black willows, alder, and silky dogwood colonized it, winding a massive network into the mud-plastered woody structure, reinforcing and eventually replacing the dam with a turfy embankment that is breached by spring's unruly spates, whose silver cascades

bring life to a cutoff stream section. But in low-water autumn this natural levee deflects a steady slide of water through alder lowlands.

In scanning the mesmerizing play of light and shadow upon the brook and all along its banks, I feel as though I have a glimpse into the soul of the season. Set against the bank's slope, my own silhouette is alive with wavering lights, golden shimmerings in a slow-moving black shadow-shape. These rippling threads are sunlight tossed from a wind-ruffled quiet backwater just off the channel's more enlivened run, where water striders serenely glide. I see that the flickering reflections can come to light only in shadow. On the radiant slope of the sun-struck stream bank, they are invisible, lights dissolved in lights. Strewn with fallen leaves bleached of their autumn brilliance, the high banking has become a glowing ocher wall, a tabula rasa for watery writing.

Within every shadow, from that of the slenderest wisp of dried sedge to those of the infinitely branched debris of former floods and broader stems of standing alder and the one I cast myself (the largest among these), there is a ceaseless wavering of amber-gold webbings of light cast by flowing and windblown water. I move, and the lights move with me, glimmering wherever my shadow goes. I cannot catch them in my hand, but I can shift them about by playing the shadow of my hand over the stream bank and place them

where I will. It is as though the brook's reflections pass through me, pass through fallen trees and tumbled ferns. Sunlight and shadows, wind and water: at this late afternoon hour in deepening autumn the world becomes translucent, immaterial.

Often on impulse, I walk out by myself:

Magnificent scenes, I alone know;

Walk to the source of the stream

And sit down to watch clouds rise.âWang Wei

T

HE SUN

is so low at this hour that it is all but impossible to look to the west, and I trail a long shadow as I make my way to the oxbow meander. Wood turtles at times take the last low sun of the year along its west-facing bank before entering the stream for their long overwintering. As I descend to the brook I see that a large red maple in the floodplain swamp has gone down, a casualty of yesterday's windstorm. This enormous windthrow obliges the deer to

take another route among the ferns. And so it obliges me, as I borrow their new trail, a replacement of the former well-worn path that led me quietly and fairly easily to a ford in the stream. The tree's great tipped-up roothold has left a crater that seems destined to become flooded next spring, forming a vernal pool that may well be appropriated by wood frogs and spotted salamanders for their breeding.

The last warm days of autumn draw me to this place at the fading light of late afternoon in the evening of the year as does the breaking forth of spring, with its dazzling new light in the morning of the year. As fall moves on toward winter and the leaves begin to thin, the low shafts of light that are allowed to touch the stream and its banks become a deeply evocative testimonial to the turning of the year. Everything they touch is graced by a near-miracle radiance in the immediate landscape. The water is low and completely still, as it generally is at this time of year. The brook rests. The wild surges of March around the oxbow bend have been forgotten. Or remembered only, I see, in the swirls of grass and sedge and drifts of flood wrack, interwoven strewings of branches, stems, leaves, and vines that perfectly trace the course and mark the height of the flood that swept through the shrub thickets of the higher bank. In this artful-seeming arrangement of the wreckage of spring spates, as if the brook had left them here for the purpose, the wood turtles do their final sun worshipping of the year.

And here I find a turtle who has been doing just that. A young one has evidently been settled here for a while; several red maple leaves, let loose in the still air to spiral down from the high canopy, have landed on his carapace and stayed there, obscuring him all the more. The shadow from the high bank across the stream has crept over him as well. But the air is warmer than the water, and it appears that he will linger on the bank before returning to the stream, which, though only thirty-seven degrees, will be warmer than the air when the temperature falls below freezing in the night.

I find no other turtlesâsignificantly, no adultsâin this place that for so many years has yielded me many of my final sightings of the year. This could well be a reflection of the toll taken by the otter predation of last winter. I have unprecedented and unwelcome tallies among my notes for this season: I have, by way of four shells I found after discovering that first lifeless wood turtle at thaw, documented five fatalities. I know the seasonal movement patterns of at least half a dozen adults whom I would have expected to encounter this season but have not. And in addition to the known dead and those I have failed to come upon, who could well have succumbed to otter attacks, I have recorded upward of thirty turtles who have lost from half a leg to one or two entire legs.

And yet, in an alder- and meadowsweet-thicketed stream

reach a quarter of a mile downstream from the confluence of two brooks, the unusually populous wood-turtle center on which I have focused, I found four intact individuals, perfect to the tips of their tails. Because this site is in active farmland, I rarely go there. But I wanted to compare its wood-turtle status with that of the area of heavy impact. I cannot count this as a definitive survey, but I certainly have to consider that the predation may have been quite localized.

And perhaps episodic as well, if considered as an outbreak set in at least several decades of minimal predation. (Many of the adult turtles I have recorded were more than twenty years old when I began to observe this colony.) Space and time are clearly factorsâI would say critical factorsâin the coexistence of wood turtles and otters over millennia, an ongoing dynamic with so many variables and interactions and a complexity that may well be ultimately indecipherable.

Seeing, which I found so difficult upon my arrival, becomes nearly impossible as I follow a turn in the brook and face into the sun. Except in the shadows of the trees I am absolutely blinded. I see better after the sun drops below a ridge of white pines to the west. Then, as light begins to slip away altogether and I make my way from the brook, I gather pale kindling in the pine grove, smooth fallen branches from which all bark has sloughed. As I leave, as

darkness deepens in the riparian landscape, a mood deepens in me of days growing shorter and the year ending. These transitions color me, as they have since my first boyhood wanderings, with a vague melancholy, even as they tinge the leaves of the streamside maples with an exuberant brilliance. I think back to a time long past when other brooks, now lost, ran wild, and I followed. Night comes on with its first small scattering of stars, and I forget what it was I was trying not to remember.

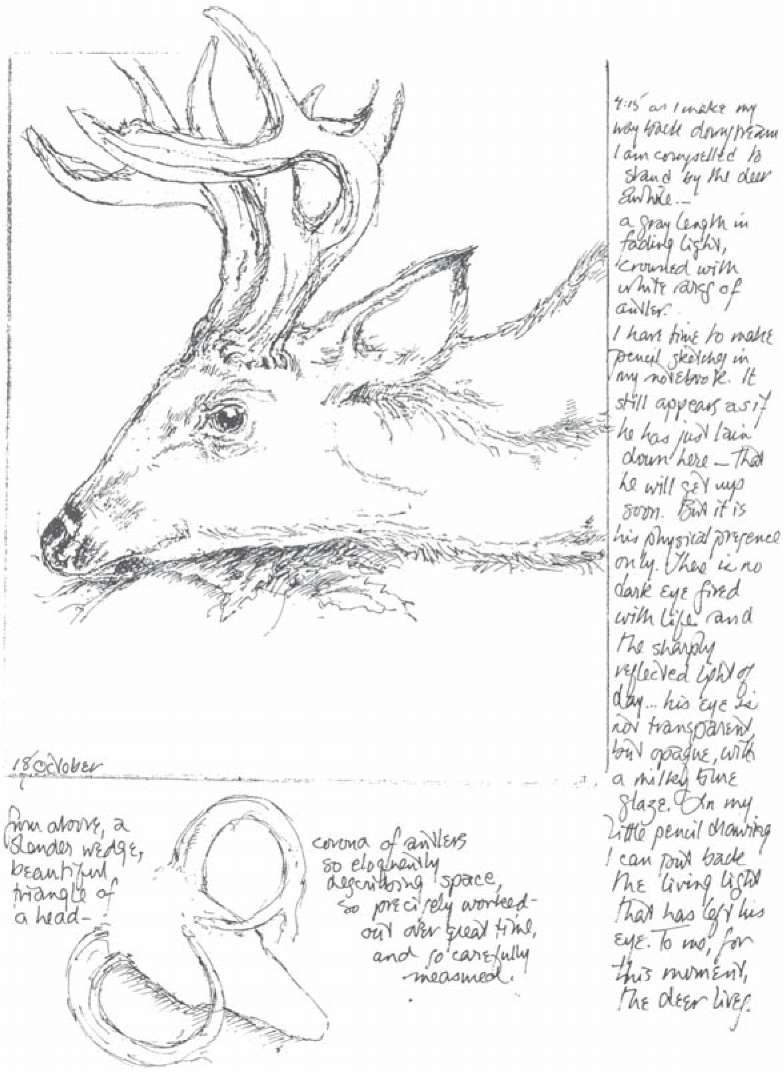

18

OCTOBER.

Walking up the autumn brook, I come upon a dead buck, a white-tailed deer lying on the mixed leaf-strewn and open mud of the bank. My eyes have been so intent on the water, and he is so well camouflagedâand so still in deathâthat as large as he is I nearly step on him before I see him. I have come close at times to living deer and have found several dead ones, in advanced decay or little more than bits of fur and bones; but I have never seen such a vision as this. Handsome in death, fallen somehow in his prime, he lies in a lifelike pose. His fur flows over his body with the grace of water flowing over stones in the nearby brook. His large earsâso largeâwhich in life could

pick up the slightest whispers of distant sound, do not hear the rushing of the water just beyond his muzzle. He would make a perfect statue of a deer in gentle stride if I were to right him. His hindquarters have been eaten at slightly ... there is some fresh blood and small scatterings of hair. I take this as the work of scavengers and not what brought him down. Even with these signs of inevitable dissolution at his flanks he is so fresh and appears dignified in death.

As I admire his form and attempt to commit it to memoryâthe sweep of gray, silvered, light fawn fur over his wonderful rib cageâhis sides seem about to heave with breath. His large, wild shape and substance, in which a heart so wildly beat not long ago, still speak of life.

I circle around him, looking from every angle, and each view describes a perfection of form and function. I see how the antlers he soon would have shed are securely set in his head, their footings reminiscent of a tree's rootedness in the earth. His antlers branch forth with a treelike twisting. Taking the antlers in my handsâI never would have expected to have such a tangible hold on a deer, such a physical bondâI rock them and discover a surprising flexibility. I raise his head and part of his muscular neck, lighter and more supple than I would have thought. It seems his eyes are about to blink, his nostrils twitch and snort. As I shift his head about, I feel as though I could raise him entire, lift him to his feet, and set him to run wild again ... as though

I could even run wild with him, leap the brook with a single bound and run like a deer through the woods.

I gently lower his head and neck and settle them precisely back in the impression they have left in the semifrozen, leaf-lined brook-side turf, the shallow cradling depression where cheek and jaw rested (did the last of his animal warmth help shape it?) and walk on up the stream.

5

NOVEMBER.

I see gleamings in the brook as I look into clear, chill water sliding over stones and cobble, gravel and sand, the streambed on which the wood turtles have settled as they begin to wait out another long winter. I find here one of the "books in running brooks" of which Shakespeare wrote, perhaps the one great book for me, one I never tire of trying to read. Now that successions of hard frost, cold rains, and wild late autumn winds have stripped the alders and silky dogwood of all their leaves, the stream is flooded with sunlight, except in runs through flats of white pine and along slopes of hemlock. Far more lit up than in deeply shaded summer, it is mostly a course through leafless miles,

its water filled with light even as the sun traces its low, edge-of-winter arc in the sky.

I could count the cobblestones that are magnified by this crystal streaming: dark stones and light and some that glint or give off a sheen when viewed from the right angle, mica, quartz, and feldspar. Something shines golden in the sand. Even if it were gold it would be but one more mineral among the many here. Raw or minted into coins, gold has no value in the economy of this wild-running stream. Only time can be spent here; it is the currency of the seasons and their workings, and all that one can ever spend here. The gleam of a gold nugget would signal no more value on the bottom of this stream than that of the soft, lustrous light given off by feldspar, the most common mineral on earth.