Fordlandia (34 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

And they used themselves as standards to measure the value of Brazilian labor. “Two of our people easily carried some timbers which twelve Brazilians did not seem to be able to handle,” observed a Dearborn official at the end of 1930. What a man could do in a Dearborn day “would take one of them guys three days to do it down there.”

5

These American managers and foremen did, after all, work for a man whose obsession with time long predated his drive to root out “lost motion” and “slack” in the workday by dividing the labor needed to build the Model T into ever smaller tasks: 7,882 to be exact, according to Ford’s own calculations. As a boy, Ford regularly took apart and reassembled watches and clocks. “Every clock in the Ford home,” a neighbor once recalled, “shuddered when it saw him coming.” He even invented a two-faced watch, one to keep “sun time” and the other Chicago time—that is, central standard time. Thirteen when his mother died giving birth to her ninth child, Henry later described his home after her passing as “a watch without a mainspring.”

6

He also knew that attempts to change the measure of time could lead to resistance—again, well before he met labor opposition to his assembly line speedup. He was twenty-two when, in 1885, most of Detroit refused to obey a municipal ordinance to promote the “unification of time,” as the campaign to get the United States to accept the Greenwich meridian as the universal standard was called. “Considerable confusion” prevailed, according to the

Chicago Daily Tribune

, as Detroit “showed her usual conservatism in refusing to adopt Standard Time.” It took more than two decades to get the city to fully “abandon solar time” and set its clocks back twenty-eight minutes and fifty-one seconds to harmonize with Chicago and the rest of the Midwest (the city would switch to eastern standard time in 1915, both to have more sunlight hours and to synchronize the city’s factories with New York banks).

7

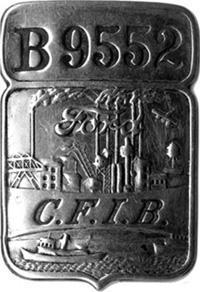

In Fordlandia, industrial regimentation entailed a host of other initiatives besides whistles and punch card clocks. The paying of set bimonthly wages, based on those punched cards, was the most obvious. So was a conception of the workday that made as little concession as possible to the weather, keeping workers “on the clock” when rain poured down in sheets and the temperature soared past 105 degrees. The effort to rationalize life reached into the smallest details of a worker’s day. As in Dearborn, plantation employees were required to wear a metal Ford badge, embossed with their ID number and an industrial panorama that included a factory complex, an airplane, two ships (the

Ormoc

and

Farge

?), and a water tower. The fieldhands who cleared the jungle and tended to the young rubber trees often took off their shirts in the heat, and so they pinned their badges to their belt buckles. The cost of a lost badge was deducted from wages.

Men line up to receive their pay

.

A worker’s badge depicting the Fordlandia ideal

.

Regimentation also extended into hygiene and health. The company required workers to submit to blood draws to test for disease and injections to vaccinate against smallpox, yellow fever, typhoid, and diphtheria. When workers went to punch out at the end of the day, they were met at the clocks by members of the medical team, who gave them their daily quinine pill. They were often reluctant to take it, though, as the high dosage prescribed by Ford’s doctors caused nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, skin rashes, and nightmares. Hiding the pills under their tongues, the workers, once out of sight, would compete to see who could spit theirs the farthest. Plantation doctors also insisted that all workers take the antiparasitical chenopodium, without, as one employee complained, examining them to see if the medicine was required. “The Americans suppose that we are all full of worms,” he said.

8

AT DAWN, WHEN the whistle gave its first blast summoning workers to their stations, Fordlandia was often still shrouded in mist. Its managers would soon learn that the fog that wafted off the Tapajós early in the morning accelerated the spread of the rubber-destroying fungi. Yet in those early days, before the blight hit, they thought it beautiful, especially when the mist mingled with light’s first rays through standing trees. The undulating hills and hollows of the planting area no longer looked like a wasteland, as over two thousand acres of six-feet-tall rubber trees, lined up in neat rows, had begun to sport young crowns of leaves. The estate was especially enchanting around the American compound. Though it was set back from the dock about a mile and a half, the row of houses nestled on a rise above a bend in the Tapajós, gave its residents a panoramic sunset view of the broad river. Behind the houses, as a buffer to the rest of the plantation, Archie Weeks had left a stand of forest, creating what residents described as a “nature park.” With most of the jungle’s dangers removed, it was easier to contemplate its pleasures. Paths raked clean of the rank, rotting leaves that normally cover the forest floor meandered through ferns, tropical palms, false cedars, and kapoks garlanded with climbers, bromeliads, bignonias, and other tropical flowers; large morpho butterflies flitted over the blossoms, their wings shining blue and black. And that December, Dearborn had sent down about a dozen live pines, to be used as Christmas trees in the American houses, so its homesick American staff could have a proper American holiday.

Slowly, before the second whistle signaled the official start of the day, the morning sounds of the forest would give way to the noise of waking families, women grinding manioc, and the chatter, first subdued and then playful, of assembling men. Most came from the bunkhouses or the plantation settlement. But a contingent commuted from the other side of the river, their canoe paddles splashing the water, oil lamps piercing the thick fog, helping them navigate, as did the occasional soft whistle if one drifted off course. Others walked from Pau d’Agua or one of the other small settlements on the plantation’s edge that had so far withstood the company’s attempts to buy them out or shut them down, continuing to offer a degree of nighttime autonomy to Fordlandia’s workers. Time cards were punched, ignitions turned, instructions given, and the workday commenced.

By the end of 1930, then, it seemed as if Fordlandia had made it through its rough start and had settled into a workable routine. Most of the physical plant was built, and crews were pushing into the jungle, clearing more land, planting more rubber, and building more roads. John Rogge, named acting manager following his return from the upper Tapajós and Victor Perini’s sudden departure, had arranged for a steady supply of seeds to be sent down from the Mundurucú reservation. Rogge had also sent David Riker earlier in the year to the upper Amazon, to Acre in far western Brazil, to secure more seeds, some of which had arrived and had been planted. Sanitation squads still policed the plantation’s thatched settlement where workers with families lived, inspecting latrines and kitchens and making sure laundry was hung properly, waste was disposed of in a hygienic manner, and corrals were kept dry, well drained, and free of feces. But managers had their hands full getting the plantation and sawmill running, so they had mostly given up insisting that all single employees live on the estate proper, though they did try to force unmarried workers to eat lunch and dinner in the company’s newly built dining hall. Nor did the administration in those early years provide much in the way of entertainment. For most employees, the workday ended at three. Apart from dinner there wasn’t much else for single men to do but to drift to the cafes, bars, and brothels that surrounded the plantation, where they could eat and drink what they wanted and pay for sex if they liked. On Sundays, small-scale traders and merchants from nearby communities arrived on canoes, steamboats, and graceful sailboats, still widely used at the time, setting up a bustling market on the riverbank, selling fruit, vegetables, meat, notions, clothes, and books.

The strikes, knife fights, and riots that marked Fordlandia’s first two years had subsided, and for all of 1930 there were no major incidents. Rogge decided that the detachment of armed soldiers that had been stationed at the camp since the 1928 riot was no longer needed. Fordlandia’s end-of-the-year report, compiled in early December 1930, praised if not the work ethic then the “docility” of Brazilian workers, who do “not resent being either shown or supervised by men of other nationalities.”

Still, Rogge kept a tug and a smaller launch at the ready—not at the main dock but up the river, accessible by a path from the American village.

THE TROUBLE STARTED in the new eating hall, a cavernous concrete warehouselike structure inaugurated just a few weeks earlier. To enforce the regulation that single workers had to take their meals on the plantation—both to discourage the patronage of bars and bordellos and to encourage a healthy diet—Rogge, back from a four-month vacation, decided after consulting with Dearborn that the cost of food would be automatically deducted from bimonthly paychecks.

The new system went into effect in the middle of December. Common laborers sat at one end of the hall, skilled craftsmen and foremen at the other; both groups were served by waiters. Workers grumbled about being fed a diet set by Henry Ford, consisting of oatmeal and canned peaches imported from Michigan for breakfast and unpolished rice and whole wheat bread for dinner. And they didn’t like the automatic pay deductions, which meant they couldn’t spend their money where they wanted. It also meant they had to form a line outside the dining hall door so that office clerks could take attendance, jotting badge numbers in their roll book. But the arrangement seemed to be working.

Then on December 20, Chester Coleman arrived in the camp to oversee the kitchens. Before having spent even a day at Fordlandia, he suggested that the plantation do away with waiter service. Fresh from his job as foreman at River Rouge, with its assembly lines and conveyor belts, Coleman proposed having all the men line up for their food “cafeteria-style.” Rogge agreed, and the change went into effect on the twenty-second. Rogge also charged the unpopular Kaj Ostenfeld, who worked in the payroll office, with the job of deducting the cost of meals from workers’ salaries and with making sure that the new plan went smoothly. Dearborn believed Ostenfeld a man of “unquestioned honesty,” though they did think he could use some refinement and suggested that at some point he be brought to Detroit for “further development.” Workers had long been unhappy with his condescending, provocative manner.

9

During the first hour or so, eight hundred men made it in and out without a problem. Ostenfeld, though, heard some of the skilled mechanics and foremen complain. “When they came from work,” he said, they expected to “to sit down at the table and be served by the waiters”—and not be forced to wait on line and eat with the common laborers. As the line began to bunch up, the complaints grew sharper. “We are not dogs,” someone protested, “that are going to be ordered by the company to eat in this way.” The sweltering heat didn’t help matters. The old mess hall had been made of thatch, with half-open walls and a tall, airy A-frame roof that while rustic looking was well ventilated. The new hall was concrete, with a squat roof made of asbestos, tar, and galvanized metal that trapped heat, turning the building into an oven.

10

Cooks had trouble keeping the food coming and the clerks took too much time recording the badge numbers. Outside, workers pushed against the entrance trying to get in. Inside, those waiting for food crowded around the harried servers, who couldn’t ladle the rice and fish onto plates fast enough. It was then that Manuel Caetano de Jesus, a thirty-five-year-old brick mason from the coastal state of Rio Grande do Norte, forced his way into the hall and confronted Ostenfeld. There was already animosity between the two men from past encounters, and as their words grew heated, workers in dirty shirts and ratty straw hats and smelling of a day’s hard work gathered round. Ostenfeld knew some Portuguese from his previous work at Rio’s Ford dealership. But that didn’t mean he fully understood de Jesus, who most likely spoke fast and with a thick working-class north Brazilian accent. Often Ford men had just enough Portuguese to get by, which could be a dangerous thing, creating situations where both parties might easily mistake obtuseness for hostility. In any case, Ostenfeld grasped what it meant when de Jesus took off his badge and handed it to him.