Fordlandia (33 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

On Sundays, when outlying Mundurucú traveled to the mission to trade their rubber, the priests and nuns urged them to attend mass. Most did, motivated less by faith than by deference to the respected Franciscans. Children sat in the front with the nuns, men took the pews, remaining in a “rigid kneeling position” throughout the service, and women sat cross-legged on the floor of the center aisle, nursing their babies as the priest said mass.

Well into the 1950s, the Mundurucú continued to have their own creation myth, as well as enchanted explanations for the mundane suffering and joys of life, some of which harmonized with Catholic theology: During the time before the beginning of time, they believed, gardens bloomed without labor and axes cut of their own accord and the only requirement was a divine injunction not to look directly at the work taking place. But the Mundurucú looked. The “axes stopped chopping, the tree trunks grew hard, and men thereafter have had to swing the axes themselves.”

Yet the idea of original sin did not take hold, nor did the concept of damnation. To the degree the Mundurucú believed in hell, they thought it a “particular destination of white people.”

15

ROGGE FINALLY CAUGHT up with Johansen and Tolksdorf a day upriver from the mission. He found the two men presiding over a large Mundurucú work crew and paying them in kind, with material purchased from a downriver trading post. After all the derelictions of the two renegades, it was their defiance of the company directive to pay wages that put an end to their adventures. Ford was adamant on this point. Indeed, when he discussed the benefits his rubber plantation would bring to Amazon dwellers, he usually did so in terms of wages. “What the people of the interior of Brazil need,” Ford declared, just at the moment Captain Oxholm was bungling the unloading of the

Ormoc

and

Farge

in Santarém, “is to have their economic life stabilized by fair returns for their labor paid in cash.”

16

Among the Mundurucú, however, money as a standard of value was unknown. Gift giving was the defining feature of their culture and economy; the exchange of food, knives, guns, and cooking utensils created a sense of identity and bound individuals, households, and settlements together in a diffuse network of reciprocity. By the time of Rogge’s arrival, the Mundurucú system of generalized sharing was being increasingly replaced by barter relations whereby individuals negotiated their exchange item for item.

*

Still, throughout the 1920s and 1930s, each transaction remained highly personalized, unlike the kind of cold, faceless exchanges associated with cash economies.

†

Rogge himself was well aware of Mundurucú custom in that regard. An observant Catholic, he had attended Christmas Eve mass at the mission and was particularly fascinated by the nuns’ handing out presents after the service ended. Over the years, the Catholic outpost had accumulated a large collection of dolls of “all shapes and sizes,” which had been donated by “every country on the globe.” And each Christmas the nuns would gather up the dolls distributed the previous year, dress them in newly sewn clothes, and hand them out to the next generation of girls. Rogge understood that the nuns were trying to imbue gift giving with a specific religious meaning to celebrate the birth of Christ (as well as to teach young children the virtue of wearing clothes). But when he was confronted with the wayward agents, Rogge’s ethnographic sensibility failed him. He accused Johansen and Tolksdorf of theft, of paying their indigenous laborers with cheap goods and pocketing the money. The two tried to defend themselves, insisting that the Mundurucú didn’t “want money.” Rogge would not relent, and after reciting the litany of scandalous stories he had heard about the men during his travels, he stripped them of their account book and discharged them. Yet whatever the motives of Johansen and Tolksdorf, when Rogge requested that the Mundurucú continue collecting rubber seeds, they refused to be paid in cash and instead demanded merchandise for the labor. So he negotiated exactly what they wanted in order to continue their gathering.

It was late January when Rogge finally headed back to Fordlandia. Carried quickly on waters made swift by the seasonal rains, the lumberjack descended in twenty minutes rapids that took three or four hours to climb. He thought about the gifts he had received from the Franciscan missionaries, which included a photograph of “Indian life,” a small wooden toy, and “some Indian relics,” and pledged to always keep them as a “remembrance of my Christmas spent among the Mundurucú Indians in the interior of Brazil.” As he approached Fordlandia, Rogge felt satisfied that he had accomplished the job that he had been “sent into the heart of Brazil to do.” Dearborn, perhaps kept in the dark about his accommodation to local custom, was too. Henry Ford named him plantation manager shortly after his return, following Victor Perini’s sudden departure owing to health reasons.

“WE LIVE AS we dream, alone,” is just one of the many thoughts that move Marlow, the narrator of

Heart of Darkness

, as he journeys upriver in search of Kurtz. Rogge, too, found the jungle educative, although decidedly less existential. “One of the things I learned on this trip,” he recounted a few years later as he reflected on his travels in the upper Tapajós, “is that no white man can live and be healthy on native diet and no matter how much good food you may have with you it is advisable to have a cook along that is known to be clean and can prepare food under trying conditions.” The lesson could seem trivial, except for the fact that food was indeed a significant source of woe, and often conflict, in the jungle. In fact, exactly one year after his pursuit of Johansen and Tolksdorf, a fight over food, sparked by a hastily made decision by Rogge himself, nearly caused the destruction of Fordlandia.

____________

*

Historian Bryan McCann, who has written widely on Brazilian music and popular culture, notes that at this time the upper Tapajós was only tenuously linked to southern Brazil and relatively recent migrant communities were receptive to new dance and music trends coming in from the Atlantic. The animated, African-based swing of the Charleston would have lent itself to the kind of informal communal celebration Luxmoore describes at Villa Nova. Residents of the village probably had seen one of the many short films or cartoons from the mid-1920s featuring the dance, either in Santarém or in one of the moving cinemas set up by itinerant movie men who roamed the backlands (figures memorialized in

Bye Bye Brasil

[1979] and

Cinema Aspirina e Urubus

[2006]). McCann also reports that the Charleston was a dance form that could easily be translated into many different cultures; in 1927, Jean Renoir’s

Charleston Parade

featured an alien who lands in postapocalypse Paris and learns to do the Charleston (Devon Record Office, Exeter, UK, Charles Luxmoore, Journal 2, 1928, 521 M–1/SS/9).

*

It would not be until the 1980s, when gold was found on their land, that the Mundurucú would completely adopt money as a universal standard of value and exchange.

†

There is a temptation to think of this kind of personalized network of gift giving as the antithesis of the rationalized industrial wage system the Ford Motor Company helped pioneer back in Michigan. Yet “wages” for Ford were always more than a simple unit of value. They were a state of mind, the key to his success both as a manufacturer and as a social engineer, as enchanted and filled with cultural meaning as was Mundurucú gift giving and bartering. “On the cost sheet,” Ford said, “wages are mere figures; out in the world, wages are bread boxes and coal bins, babies’ cradles and children’s education—family comforts and contentment.” Nor was he above using gifts to create personal bonds of loyalty. He paid Harry Bennett, for instance, only a small yearly salary yet showered him with presents, including several yachts, houses, and even an island mansion in the Huron River. “Never,” he once tutored Bennett, “give anything without strings attached to it” (Collier and Horowitz,

The Fords

, p. 132; “Life with Henry,”

Time

, October 8, 1951).

CHAPTER 15

KILL ALL THE AMERICANS

IN DECEMBER 1930, WORKERS HAD FINISHED PAINTING THE FORD logo on the landmark that distinguishes Fordlandia to this day: its 150-foot tower and 150,000-gallon water tank. “When the view is had from the deck of a river steamer,” wrote Ogden Pierrot, an assistant commercial attaché assigned to the US embassy in Rio, of his trip to Fordlandia, “the imposing structures of the industrial section of the town, with the tremendous water tank and the smokestack of the power house, catch the view and create a sensation of real wonderment.”

He went on:

This is not unusual when it is considered that for several days the only signs of life that have relieved the monotony of the trip have been occasional settlements consisting of two or three thatched huts against a background of green jungle. A feeling akin to disbelief comes over the visitor on suddenly seeing projected before him a picture which may be considered a miniature of a modern industrial city. Smokestacks belching forth a heavy cloud formed by waste wood used as fuel, a locomotive industriously puffing along ahead of flat cars laden with machinery just received from the United States, steam cranes performing their endless half turns and reverses for the purposes of retrieving heavy cargo from the holds of lighters moored alongside the long dock, heavy tractors creeping around the sides of the hills dragging implements behind them for loosening and leveling the earth, others heaving at taut cables attached to stumps of tremendous proportions—all combine to increase the astonishment caused in the uninitiated visitors to this district, who had no conceptions of what had been accomplished in the brief space of slightly over two years.

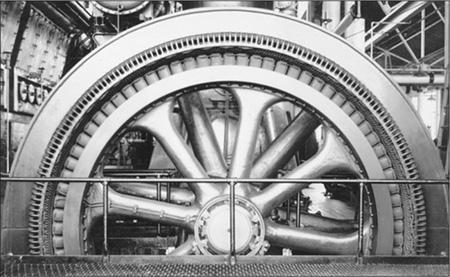

Industrial sublime: Fordlandia’s powerhouse turbine

.

Much of the piping that would provide indoor plumbing to the town was scheduled to be completed the following year. But as Christmas approached, workers bolted to the tower one feature that had nothing to do with water.

1

IT TOOK DEARBORN’S purchasing agents some effort to find a factory whistle that wouldn’t rust from the jungle humidity. Once they did, they shipped it to Fordlandia, where it was perched on top of the water tower, above the tall trees, giving it a seven-mile range. The whistle was piercing enough not only to reach dispersed road gangs and fieldhands but to be heard across the river, where even those not affiliated with Fordlandia began to pace their day to its regularly scheduled blows. The whistle was supplemented by another icon of industrial factory work: pendulum punch time clocks, placed at different locations around the plantation, that recorded exactly when each employee began and ended his workday.

2

In Detroit, immigrant workers by the time they got to Ford’s factories, even if they were peasants and shepherds, had had ample opportunity to adjust to the meter of industrial life. The long lines at Ellis Island, the clocks that hung on the walls of depots and waiting rooms, the fairly precise schedules of ships and trains, and standardized time that chopped the sun’s daily arc into zones combined to guide their motions and change their inner sense of how the days passed.

But in the Amazon, the transition between agricultural time and industrial time was much more precipitous. Prior to showing up at Fordlandia, many of the plantation’s workers who had lived in the region had set their pace by two distinct yet complementary timepieces. The first was the sun, its rise and fall marking the beginning and end of the day, its apex signaling the time to take to the shade and sleep. The second was the turn of the seasons: most of the labor needed to survive was performed during the relatively dry months of June to November. Rainless days made rubber tapping possible, while the recession of the floods exposed newly enriched soils, ready to plant, and concentrated fish, making them easier to catch. But nothing was set in stone. Excessive rain or prolonged periods of drought or heat led to adjustments of schedules. Before the coming of Ford, Tapajós workers lived time, they didn’t measure it—most rarely ever heard church bells, much less a factory whistle. It was difficult, therefore, as David Riker, who performed many jobs for Ford, including labor recruiter, said, “to make 365-day machines out of these people.”

3

Fordlandia’s managers and foremen, in contrast, were mostly engineers, precise in their measurement of time and motion. One of the first things the Americans did was set their watches and clocks to Detroit time, where Fordlandia remains to this day (nearby Santarém runs an hour earlier).

*

They scratched their heads when confronted with workers they routinely described as “lazy.” Archie Weeks’s daughter remembers her father throwing his straw hat on the ground more than once in frustration. With a decided sense of purpose that grated against the established rhythms of Tapajós life (David Riker liked to say that

hurry

was an “obscene” word in the valley), proudly affiliated with a company renowned for its vanguard interlocking efficiency, Ford’s men tended to treat Brazilians as instruments. And called them such. Matt Mulrooney gave his workers nicknames. “This fellow I had named Telephone. When I wanted to send a message or an order down front, I’d just holler, ‘Telephone!’ and he’d show up.”

4