Frozen in Time (16 page)

Abundantly clear to Beattie after removing more than 3 feet (1 metre) of permafrost, was that Torrington's preservation would probably be excellent because of the ice. Originally there had been some doubt, as 138 Arctic springs and summers had passed. But even at the height of summer the season's heat had had little or no effect on the upper reach of the permafrostâand Franklin's men had gone to a good deal of trouble interring Torrington deep in the frozen ground. Then, as the researchers waited for the permits, they were confronted with a problem that could have ruined the whole project. Water began to ï¬ood the grave.

The water was subsurface run-off from the melting snow and permafrost of the slope and cliffs inland from the excavation, further fed by periods of rain and sleet. Everything was at stake. What had lain undisturbed for more than a century could be severely damaged or destroyed by water within hours if they didn't act quickly.

It was decided that a shallow V-shaped ditch 130 feet (40 metres) long would be dug directly upslope of the graves (the three crewmen were buried alongside one another, with Torrington closest to the sea). This ditch, shovelled and scraped only a few inches into the permafrost, would act as a collecting canal, effectively diverting the water away from the graves. Within a matter of hours, the water seeping into Torrington's grave had slowed to a trickle; eventually it stopped.

With still no news about the required permits, Roger Amy and Geraldine Ruszala made use of the down time to explore the spit of land connecting Beechey Island to Devon Island. Well into their hike, Amy, casting his eye along the spit, noticed a dirty-coloured snowbank about .125 of a mile (.2 km) away. His eyes were drawn by its unusual colour, but, as he looked more closely, he saw it move. Amy stopped dead in his tracks as the realization hit him: they were walking directly into the path of a polar bear. These huge and powerful animals, which can weigh 1,985 pounds (900 kg) and stand 11.5 feet (3.5 metres) on their hind legs, often avoid human contact. However, periodic polar bear attacks do take place in the Canadian Arctic.

Amy whispered to Ruszala to start slowly backing up as the bear began sauntering towards them. They were at least .33 of a mile (.5 km) from camp, but they continued this cautious retreat almost the whole distance, with the bear following along at the same speed. Finally, with the camp within carshot, they turned and ran. “A bear, a bear,” Ruszala shouted, wildly pointing back towards the spit. The bear was still about one eighth of a mile away when Kowal and Damkjar ï¬red several shots into the air to frighten the animal. These ï¬rst blasts simply increased the bear's curiosity, but the two men continued ï¬ring and, after ambling a few feet closer, the bear wisely decided it might be betterâif not simply quieterâto alter its course and move on to other business. The crew followed the majestic animal's retreat until it was last seen swimming speedily across Union Bay towards Cape Spencer. Amy and Ruszala, however, were badly shaken by the experience of being stalked.

As the wait for the ï¬nal permits continued, Beattie and Damkjar decided to explore the remains of Franklin's winter camp, then the historic sites along the east coast of the island.

Most of the relics left behind by Franklin's expedition had already been collected and taken away by the search expeditions that followed. Those that remained were subjected to continual disturbance right up to 1984. Despite this, a number of important artefacts could be seen in the areas adjacent to the graveyard. Most prominent among them was a large gravel-walled outline, believed to have been a storehouse. Also nearby the graves were the remains of a smithy, a carpenter's shop and, further away, depressions where tent structures or observation platforms once stood. (Between 1976 and 1982, Parks Canada had conducted detailed archaeological investigations of a number of important historical sites in the Arctic. Beechey Island was one of the sites studied. The only artefacts from Franklin's expedition remaining at that timeâbesides the structure outlinesâwere clay pipe fragments, nails, forge waste, a stove door fragment, wood shavings and tin cans.)

Beattie also looked over two graves dating from the searches of the 1850s that had been dug alongside Torrington, Hartnell and Braine. One of the graves was that of Thomas Morgan, a seaman from Robert McClure's ship, the HMS

Investigator.

The owner of the other grave is unknown, though one journal from the 1850s indicates that it may be a dummy grave serving as a memorial to French Navy Lieutenant Joseph René Bellot. Both of these men had died heroic and tragic deaths. Morgan had been among the scurvy-wracked from the

Investigator

whoâbefore the Franklin expedition achievements were discoveredâhad been credited with being the ï¬rst to cross the Northwest Passage. Having abandoned the ice-locked

Investigator

with the rest of McClure's crew at Mercy Bay on the north coast of Banks Island, Morgan had made the difficult trek by foot over the ice ï¬rst to Dealy Island, then later reached Beechey Island, only to die aged thirty-six in May 1854 on board the HMS

North Star.

Bellot, who had served in the French Navy with distinction, later volunteered to join in the Franklin search. Bellot visited the Arctic ï¬rst under Captain William Kennedy aboard the

Prince Albert,

then later aboard the HMS

Phoenix.

On 18 August 1853, while carrying dispatches to searcher Sir Edward Belcher up icy Wellington Channel, Bellot was caught by a gust of wind and swept into the frigid water. His body was never recovered.

Beattie and Damkjar, leaving the graves and adjacent Franklin campsite behind them, walked south along the beach ridge above the waterline. The ï¬rst artefacts found along their route were tins, scattered individually or in small clusters. Close inspection of the cans identiï¬ed them as being from the supplies of the search expeditions. Not only had Captain Horatio Thomas Austin and Captain William Pennyâthe searchers who had ï¬rst discovered Franklin expedition relics on Beechey Islandâspent time here, but others later used the island as a base for their searches. Walking along, the number of tins increased and wood fragments also became evident. Visible around a curve in the coastline was the mast of one of several vessels left at King William Island during the 1850sâjutting at a steep angle out of a gravel beach ridge. The vessel, which was probably left on the island to serve as a depot, was still largely intact in 1927 when Sir Frederick Banting, codiscoverer of insulin, and Canadian painter A.Y. Jackson visited the island on a sketching trip. The mast, and a small section from the hull of the vessel, which lay ï¬at on one of the lower beach ridges, were all that remained for Beattie and Damkjar to inspect.

Owen Beattie standing at the ruin of Northumberland House, the supply depot built in 1854 by the crew of the North Star, part of the ï¬eet commanded by Belcher.

Eric Damk- jar inspecting the monument erected by Sir Edward Belcher to commemorate all those who died searching to discover the fate of Franklin's expedition.

Along one of the highest beach ridges was a series of recent markers and cairns dating from the 1950s to the 1970s. Also at the site: a memorial combining the monument left by Leopold M'Clintock in 1858 and a cenotaph erected by Belcher as a memorial to all those who died during the Franklin search.

Belcher, commanding a British naval ï¬eet of ï¬ve ships from 1852 to 1854, ordered that one of these ships, the

North Star,

under the command of William John Samuel Pullen, remain off Beechey Island as a base for the other vessels. Directly in front of the cenotaph, on a much lower ridge, is the skeleton of Northumberland House, the supply depot built by the crew of the

North Star

in 1854. It had been in a reasonable and useful state of repair even into the early 1900s, but no longer. Only parts of the wood walls were still visible, though a stone wall had held up quite well. Scattered in and around the structure were hundreds, possibly thousands, of artefacts from the structure itself and the food containers (primarily wooden barrel staves and metal barrel hoops) once housed inside. On 6 August 1927, when Banting and Jackson visited Northumberland House, signiï¬cant damage had already been done to the structure, though Jackson noted in his journal that “there are a lot of water barrels, thirty or forty of them, that could be used today.” Banting, however, also noted that “Bears had chewed holes in the side of some of the barrels, large enough to admit the head and neck so that they could get the last drop of the contents.” Still, the scattered relics on Beechey Island do not attest to the hundreds of men, from various expeditions, who spent time at the site over the course of the searches of the early 1850s. Even on such a small island, their artefacts are lost among the forbidding landscape.

Peering off the south shore of the island during his survey, Beattie thought of the wreck of the

Breadalbane,

sent from England with fresh supplies for the ships under Belcher. Crushed in the ice, the

Breadalbane

sank off the island on 21 August 1853. In 1980, Canadian underwater explorer Dr. Joe MacInnis located the remains of the remarkably preserved ship under 330 feet (100 metres) of water and, in 1983, led a diving team to visit the wreck.

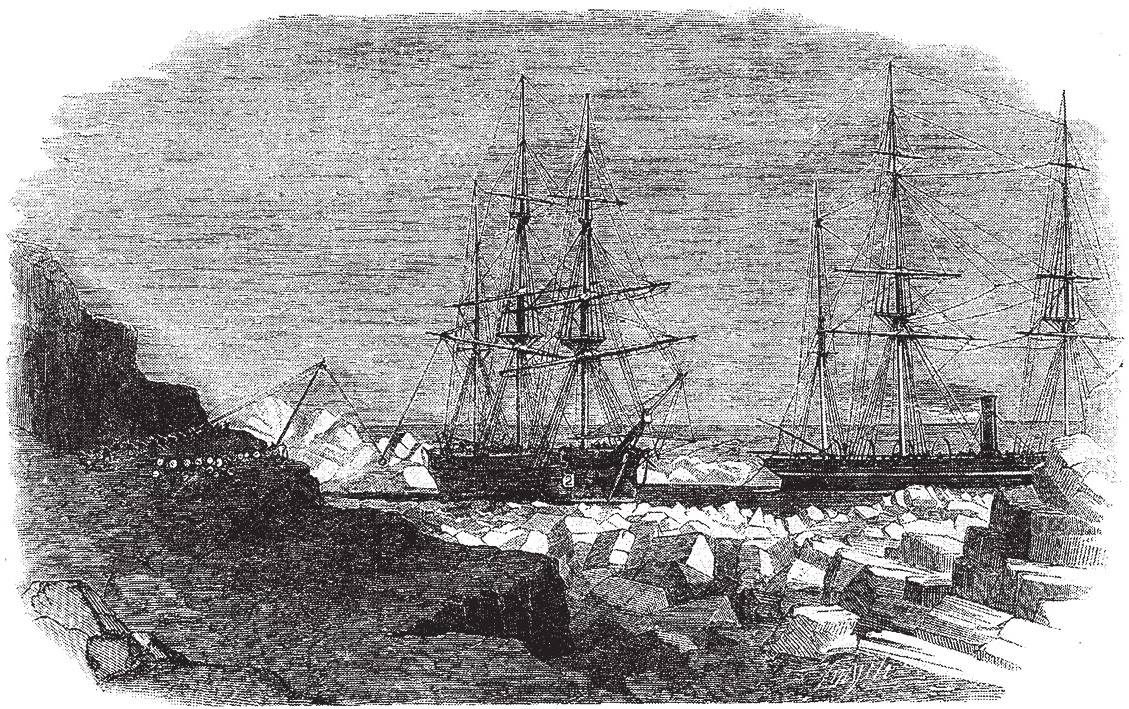

HMS Breadalbane (left) and HMS Phoenix landing provisions at Cape Riley.

Returning to camp from his hike, Beattie saw that the wait for permissions was taking its toll on everyone's nerves. Feeling that the permissions would not be granted in time to complete the project that summer, Amy ï¬nally decided to return to Edmonton, where he had a number of pressing professional obligations. He left Beechey Island on 15 August.

At last, on 17 August, Beattie received a radio transmission from the Polar Shelf offices in Resolute giving permission to proceed with the exhumation, autopsy and reburial of John Torrington. Hearing the letters of permission read over the radio caused a great sense of relief and fuelled a new surge of energy and enthusiasm. The last letter also detailed the procedures to follow should contagious disease be detected in the Franklin crewmen. Everyone in the Arctic could have picked up the transmission and heard the Polar Shelf radio operator read in part: “If, in the course of the excavations, Dr. Beattie discovers any evidence of infectious disease in the artefacts or corpses exhumed, further digging should be discontinued.”

Work on clearing off the last layer of ice and gravel began almost immediately, and the source of the noxious odour soon became apparent. It was not partly decomposed tissue, as had been expected, but rather the rotting blue wool fabric that covered the coffin.

As they reached the coffin lid, the wind picked up dramatically and a massive black thunder cloud moved over the site. The walls of the tent covering the excavation began to snap loudly, and, as the weather continued to worsen, the ï¬ve researchers ï¬nally stopped their work and looked at one another. The conditions had suddenly become so strange that Kowal observed, “This is like something out of a horror ï¬lm.” Some of the crew were visibly nervous and Beattie decided to call a halt to work for the day. That night the wind howled continuously, rattling the sides of Beattie's tent all night and sometimes smacking its folds against his face, making sleep difficult. Ruszala, unable to sleep, stayed in one of the long-house tents. All were concerned about the stability of the tent that had been erected over Torrington's grave and, through the night, anxious heads would peer out of their tents to check on it. Towards morning, a violent gust slashed its way under the ï¬oorless tent, lifting it up and over the headboard before slamming it down on the adjacent beach ridge. Only a single rope held to its metal stake, preventing the tent from blowing into Erebus Bay. In the morning, the weather ï¬nally calmed and they dismantled the tent, remarkably only slightly damaged, and continued their excavation in the open.