Galileo's Daughter (19 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Even as Prince Cesi and Galileo discussed these prospects, news from Rome on April 11 dampened their spirits: Virginio Cesarini, the prince’s cousin and their fellow Lyncean Academician, immortalized as the addressee of

The Assayer,

had died at twenty-seven of tuberculosis.

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

WHAT GREAT HAPPINESS was delivered here, Sire, along with the news (via the letter that you ordered sent to Master Benedetto [Landucci]) of the safe progress of your journey as far as Acquasparta, and for all of this we offer thanks to God, Master of all. We are also delighted to learn of the favors you received from Prince Cesi, and we hope to have even greater occasion for rejoicing when we hear tell of your arrival in Rome, Sire, where persons of grand stature most eagerly await you, even though I know that your joy must be tainted with considerable sorrow, on account of the sudden death of Signor Don Virginio Cesarini, so esteemed and so loved by you. I, too, have been saddened by his passing, thinking only of the grief that you must endure, Sire, for the loss of such a dear friend, just when you stood on the verge of soon seeing him again; surely this event gives us occasion to reflect on the falsity and vanity of all hopes tied to this wretched world.

But, because I would not have you think, Sire, that I want to sermonize by letter, I will say no more, except to let you know how we fare, for I can tell you that everyone here is very well indeed, and all the nuns send you their loving regards. As for myself I pray that our Lord grant you the fulfillment of your every just desire.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 26TH DAY OF APRIL 1624.

Most affectionate daughter,

S.M.Coloste

This is the only letter of Suor Maria Celeste’s that Galileo salvaged from the tumult of 1624. More than a year separates it from the next in his collection, so that her response to his intercession with the pope on San Matteo’s behalf is lost in the lacuna. (That Galileo petitioned effectively, however, is borne out by later letters that mention “our Father Confessor” in complete comfort, as someone who sends regards to Galileo, even watches Galileo’s house for him when he is out of town, and once asks for help settling some personal business in Rome.)

Galileo rode into Rome on April 23. The following day, Pope Urban received him congenially in a private audience for the first time—and then five more times in as many weeks over the course of Galileo’s stay. The old friends strolled through the Vatican Gardens for an hour at a time, treating all the topics Galileo had hoped to discuss with His Holiness.

Although no one recorded the content of Galileo’s springtime sessions with Urban in 1624, there can be little doubt they assessed the fallout from the momentous decree that had dominated their last days together. Many Italian scientists felt their hands tied by the Edict of 1616. Outside Italy, however, few heeded the anti-Copernican ruling. As Galileo probably knew from his correspondents across Europe, no astronomer in France, Spain, Germany, or England had even bothered to make the required corrections to

De revolutionibus

published in 1620. In a sense, the edict had made Italy lose face among scientists abroad. There were rumors, too—to make Urban wince—of Germans on the verge of converting to Catholicism who backed away because of the edict.

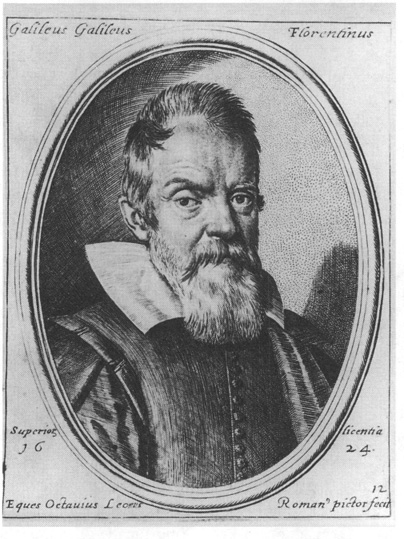

Engraving of Galileo at age sixty, by Ottavio Leoni

Urban, now more than halfway through the first year of his pontificate, was proud to say he had never supported that decree, and that it would not have seen the light had he been pope in those days. As a cardinal, he had successfully intervened, along with his colleague Bonifazio Cardinal Caetani, to keep “heresy” out of the edict’s final wording. Thus, although the consultors to the Holy Office had called the immobility of the Sun “formally heretical” in their February 1616 report, the March 5 edict merely stated that the doctrine was “false” and “contrary to Holy Scripture.”

Why had Maffeo Barberini, a man with no vested interest in the Sun-centered universe, taken such action? His admiration for Galileo could well have figured in his thinking. But he no doubt had other reasons, too. Both Cardinal Barberini and Cardinal Caetani, having studied some astronomy, distinguished themselves from theologians who never looked up to Heaven except to pray. Neither cardinal believed in the physical reality of the heliocentric universe, of course, but they recognized its merit as a way of thinking about cosmology. They also valued

De revolutionibus

itself as a mathematical tour de force, and they wanted to preserve the intellectual freedom of Catholic scholars to read it—pending certain revisions. (Cardinal Caetani argued so strongly in favor of the book, in fact, that he was later chosen as the one to amend it.)

The eight years since the edict had not swayed Urban from his position on Copernicus. He still saw no harm in using the Copernican system as a tool for astronomical calculations and predictions. The Sun-centered universe remained merely an unproven idea—

without,

Urban felt certain, any prospect of proof in the future. Therefore, if Galileo wished to apply his science and his eloquence to a consideration of Copernican doctrine, he could proceed with the pope’s blessing, so long as he labeled the system a hypothesis.

By the time Galileo started back to Florence on June 8, he had secured not only the promise of a pension for Vincenzio and redress for San Matteo, but a personal letter from Urban to young Ferdinando, in which the pope lauded the grand duke’s premier philosopher: “We embrace with paternal love this great man whose fame shines in the heavens and goes on Earth far and wide.”

All these favorable words and gestures heartened Galileo, convinced him that he could indeed resume his public musings about an Earth in motion about the Sun. Before attempting the book-length tome, however, Galileo decided to write something along its lines as a trial run, by replying to an anti-Copernican treatise that had circulated through Rome since 1616. Though unpublished, the still uncontested comments of Monsignor Francesco Ingoli, secretary of the Congregation of the Propagation of the Faith, seemed to beg for a response—especially as these comments had originated in a debate with Galileo.

In 1616, during Galileo’s aggressive Copernican campaign in Rome, he had staged one of his evening disputes against the very same Ingoli. Afterward, the two of them agreed to write down their respective positions. No sooner had Ingoli done his half, however, than the Edict of 1616 intruded, leaving the written phase of the contest incomplete. Even now, Galileo hesitated to take on a man like Ingoli, who had based many of his points on theology instead of astronomy. However, he began drafting the ticklish response immediately upon his return to Bellosguardo.

“Eight years have already passed, Signor Ingoli,” Galileo began, “since while in Rome I received from you an essay written almost in the form of a letter addressed to me. In it you tried to demonstrate the falsity of the Copernican hypothesis, concerning which there was much turmoil at that time.”

Having refreshed Ingoli’s memory of the events, Galileo excused his own silence as the only appropriate response to the weakness of Ingoli’s arguments. Galileo could have swatted these away in a single blow—except, of course, the theological ones— but he simply hadn’t bothered to refute Ingoli because he deemed the effort a waste of time and breath.

“However,” Galileo continued, “I have now discovered very tangibly that I was completely wrong in this belief of mine: having recently gone to Rome to pay my respects to His Holiness Pope Urban VIII, to whom I am tied by an old acquaintance and by many favors I have received, I found it is firmly and generally believed that I have been silent because I was convinced by your demonstrations. . . . Thus I have found myself being forced to answer your essay, though, as you see, very late and against my will.”

Galileo applied all his talents of tact in this letter, not so much to suffer Ingoli—whom he variously insulted for bringing forth absurdities, for basing discussions on idle imagination, and for uttering great inanities—but rather to handle the theological overtones of the Copernican controversy with all necessary caution: “Note, Signor Ingoli, that I do not undertake this task with the thought or aim of supporting as true a proposition which has already been declared suspect and repugnant to a doctrine higher than physical and astronomical disciplines in dignity and authority.”

Instead, Galileo made it clear that he replied to rectify his own reputation, and to show Protestants to the north who had no doubt read Ingoli’s manuscript—notably Kepler—that Catholics in general understood much more about astronomy than Ingoli’s essay might lead them to believe.

“I am thinking about treating this topic very extensively,” confessed Galileo, “in opposition to heretics, the most influential of whom I hear accept Copernicus’s opinion; I would want to show them that we Catholics continue to be certain of the old truth taught us by the sacred authors, not for lack of scientific understanding, or for not having studied as many arguments, experiments, observations, and demonstrations as they have, but rather because of the reverence we have toward the writings of our Fathers and because of our zeal in religion and faith.”

Italian astronomers, in other words, could tolerate the cognitive dissonance of admiring Copernicus on a theoretical level, while rejecting him theologically. “Thus, when they [Protestants] see that we understand very well all their astronomical and physical reasons, and indeed also others much more powerful than those advanced till now, at most they will blame us as men who are steadfast in our beliefs, but not as blind to and ignorant of the human disciplines; and this is something which in the final analysis should not concern a true Catholic Christian—I mean that a heretic laughs at him because he gives priority to the reverence and trust which is due to the sacred authors over all the arguments and observations of astronomers and philosophers put together.”

Galileo could not repeat his real reasons for embracing both Copernicus and the Bible, as expressed in his

Letter to Grand Duchess Cristina,

for the edict had indeed prohibited that kind of exegesis. For the moment—and the unforeseeable future—he let his Catholic faith dictate the form in which he framed his arguments.

From this safe position, Galileo found he could once again dare to defend Copernicus:

For, Signor Ingoli, if your philosophical sincerity and my old regard for you will allow me to say so, you should in all honesty have known that Nicolaus Copernicus had spent more years on these very difficult studies than you had spent days on them; so you should have been more careful and not let yourself be lightly persuaded that you could knock down such a man, especially with the sort of weapons you use, which are among the most common and trite objections advanced in this subject; and, though you add something new, this is no more effective than the rest. Thus, did you really think that Nicolaus Copernicus did not grasp the mysteries of the extremely shallow Sacrobosco?

*

That he did not understand parallax? That he had not read and understood Ptolemy and Aristotle? I am not surprised that you believed you could convince him, given that you thought so little of him. However, if you had read him with the care required to understand him properly, at least the difficulty of the subject (if nothing else) would have confused your spirit of opposition, so that you would have refrained or completely abstained from taking such a step.