Galileo's Daughter (21 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

He occupied himself with other interests of his own and his official duties as philosopher to the grand duke, who called on Galileo to evaluate the schemes and machines that enterprising inventors tried to sell the Tuscan government. One such offering purported to pump water with miraculous efficiency, and another to revolutionize the milling of grain. After attending model demonstrations, Galileo would write polite but often daunting letters to the inventors, explaining the hopelessness of their ideas on the basis of the principles of simple machines.

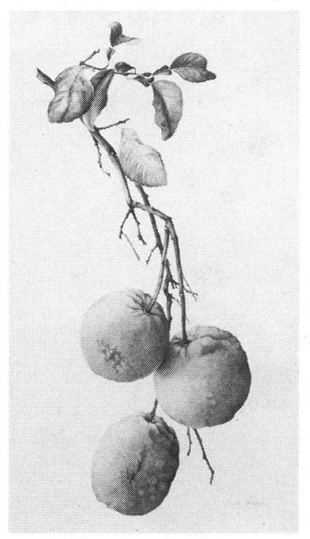

Branch of an orange tree

“I cannot deny that I was admiring and confused when, in the presence of the Grand Duke and other princes and gentlemen, you exhibited the model of your machine, of truly subtle invention,” Galileo began his critique of the would-be water pump. “And since I long ago formed the idea, confirmed by many experiments, that Nature cannot be overcome and defrauded by art,” he added soon after, “I have made an accumulation of thoughts and have decided to put them on paper and communicate them to you in order that if the success of your truly acute invention is seen in practice, and in very large machines, I may be excused by you, and through you excused by others.”

At the same juncture in 1625, Galileo also gave mathematical critiques on papers he received from his correspondents in Pisa, Milan, Genoa, Rome, and Bologna concerning their thoughts on the dynamics of river flow, the refraction of light, the acceleration of bodies in fall, and the nature of indivisible points.

In his spare time Galileo repaired to his garden, where he indulged the pleasure he had described of planting orange seeds— and lemons and chartreuse-colored citrons—in large terracotta pots. Galileo regularly sent the best of the citrons to Suor Maria Celeste, who would seed, soak, dry, and sweeten them over a period of several days to prepare his favorite confection. Having fared poorly with the fruits he consigned to her just before Christmas 1625, however, she sought a few other tokens she hoped would please him.

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

AS FOR THE CITRON, which you commanded me, Sire, to make into candy, I have come up with only this little bit that I send you now, because I am afraid the fruit was not fresh enough for the confection to reach the state of perfection I would have liked, and indeed it did not turn out very well after all. Along with this I am sending you two baked pears for these festive days. But to present you with an even more special gift, I enclose a rose, which, as an extraordinary thing in this cold season, must be warmly welcomed by you. And all the more so since, together with the rose, you will be able to accept the thorns that represent the bitter suffering of our Lord; and also its green leaves, symbolizing the hope that we nurture (by virtue of this holy passion), of the reward that awaits us, after the brevity and darkness of the winter of the present life, when at last we will enter the clarity and happiness of the eternal spring of Heaven, which blessed God grants us by His mercy.

And ending here, I give you loving greetings, together with Suor Arcangela, and remind you, Sire, that both of us are all eagerness to hear the current state of your health.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 19TH DAY OF DECEMBER 1625.

Most affectionate daughter,

S. M. Colost

I am returning the tablecloth in which you wrapped the lamb you sent; and you, Sire, have a pillowcase of ours, which we put over the shirts in the basket with the lid.

The garden at the Convent of San Matteo in Arcetri, where a rose could bloom at Christmastime, devoted much of its earthly paradise to herbs and medicinal plants the likes of rosemary (good for treating nausea) and rue (applied directly to the nostrils to stanch a bloody nose, or drunk with wine for headache). These grew among the pine, plum, and pear trees ranged around a central well in back of the church. Even the decorative rosebushes served an apothecary’s purpose, for the syrup of cooked, compressed rosebuds made an excellent purgative (prepared from several hundred roses, picked when the buds were half open, then steeped a full day and night in sugar and hot water). Just beyond the garden, the fragrant almond trees and evergreen olive trees cascaded down the slope behind the convent, where walkways led the nuns easily into Franciscan communion with Nature.

The convent’s walled perimeter, not to mention the rule of enclosure, detained Suor Maria Celeste in an anteroom of the afterlife. Rather than resent this separation from worldly affairs, cloistered monks and nuns at that time typically developed fierce attachments to their self-contained communities, where some spent long lifetimes (like the aunt of Pope Urban VIII who lived eighty-one years at her convent), and where, according to contemporary record books, miracles occurred as matters of course. A statue of the Blessed Virgin might weep or bow her head above the blue-flowered rosemary shrubs. Bones of saints buried in the on-site cemetery could be heard rattling to herald the death of a nun.

Florentine monasteries also guarded an abundance of holy relics, including fifty-one authentic thorns from the crown of Jesus and the tunic worn by Saint Francis of Assisi when the stigmata first appeared on his body.

The difference Suor Maria Celeste discerned between this vale of tears and the harmony of Paradise precisely echoed Aristotle’s distinction between corruptible Earthly matter and the immutable perfection of the heavens. This consonance was no coincidence, but the fruit of the labors of the prolific Italian theologian Saint Thomas Aquinas, who grafted the third-century-B.C. writings of Aristotle onto thirteenth-century Christian doctrine. The compelling works of Saint Thomas Aquinas had reverberated through the Church and the nascent universities of Europe for hundreds of years, helping the word of Aristotle gain the authority of holy writ, long before Galileo began his book about the architecture of the heavens.

A small and

trifling body

By 1626, Galileo had neglected his

Dialogue

for so long that his friends feared he might never return to it. And if not Galileo, then who would step forward to correct humanity’s self-centered view of the cosmos? Who better than Galileo to propound the most stunning reversal in perception ever to have jarred intelligent thought: We are not the center of the universe. The immobility of our world is an illusion. We spin. We speed through space. We circle the Sun. We live on a wandering star.

The apparent steadiness of the Earth lulls the mind into a false stability. The body’s footing feels so secure that the mind naturally interprets the daily bobbing up and down of the Sun, the Moon, the planets, and the stars as motions entirely external to the Earth. Even at night, under the open sky, assaulted by the intimations of infinity scintillating through the cope of heaven, the mind would rather cede revolution to the universe than relinquish the solace of solid ground.

This incontrovertible perception of Earthly rest gains support on every hand. The halting drop of each autumn leaf adds weight to the case for stillness. Indeed, if the Earth really turned toward the east at high velocity, falling leaves would all scatter to the west of the trees. Wouldn’t they?

Wouldn’t a cannon fired to the west carry farther than a salvo to the east?

Wouldn’t birds lose their bearings in midair?

These questions doubting the Earth’s diurnal motion consumed the participants in the

Dialogue

throughout Day Two of their deliberations.

Here Galileo demonstrated that the moving Earth—if it did indeed move—would impart its global motion to all Earthly objects. Instead of having to fight this movement in one direction and be abetted by it in the other, they would own it themselves, just as the passengers aboard a ship may saunter up or down the decks as their bodies travel—with more rapid motion, through no effort of their own—the two thousand miles from Venice to Aleppo.

As he built up the evidence for the Copernican thesis, Galileo interjected protective reminders regarding his own neutrality. “I act the part of Copernicus in our arguments and wear his mask,” Salviati explains to his two companions. “As to the internal effects upon me of the arguments which I produce in his favor, I want you to be guided not by what I say when we are in the heat of acting out our play, but after I have put off the costume, for perhaps then you shall find me different from what you saw of me on the stage.”

Thus freed to debate all the more forcefully, Salviati shows how a cannon pointed east moves east along with the Earth, as does the cannonball loaded inside it. After firing, therefore, the eastward shot has no trouble flying as far as a westward one. Nor do birds, though they fly slower than the Earth turns, find their flight adversely affected by the diurnal rotation. “The air itself through which they wander,” notes Salviati, “following naturally the whirling of the Earth, takes along the birds and everything else that is suspended in it, just as it carries the clouds. So the birds do not have to worry about following the Earth, and so far as that is concerned they could remain forever asleep.”

As participants in the Earth’s activity, people cannot observe their own rotation, which is so deeply embedded in terrestrial existence as to have become insensible.

“Shut yourself up with some friend in the main cabin below decks on some large ship,” Salviati suggests later on the second day,

and have with you there some flies, butterflies, and other small flying animals. Have a large bowl of water with some fish in it; hang up a bottle that empties drop by drop into a wide vessel beneath it. With the ship standing still, observe carefully how the little animals fly with equal speed to all sides of the cabin. The fish swim indifferently in all directions; the drops fall into the vessel beneath; and, in throwing something to your friend, you need throw it no more strongly in one direction than another, the distances being equal; jumping with your feet together, you pass equal spaces in every direction. When you have observed all these things carefully (though there is no doubt that when the ship is standing still everything must happen in this way), have the ship proceed with any speed you like, so long as the motion is uniform and not fluctuating this way and that. You will discover not the least change in all the effects named, nor could you tell from any of them whether the ship was moving or standing still.

Remarkably, Galileo conceded through this early demonstration in relativity,

no experiment

performed with ordinary objects on the surface of the Earth could prove whether or not the world was actually turning. Only astronomical evidence and reasoning from simplicity could carry the argument. Thus the daily rotation of the Earth streamlined the hubbub of the universe and recognized the cosmic balance of power. For if the heavens really revolved with enough force to propel the vast bodies of the innumerable stars, how could the puny Earth resist the tide of all that turning?

“We encounter no such objections,” Salviati replies to his own rhetorical question, “if we give the motion to the Earth, a small and trifling body in comparison with the universe, and hence unable to do it any violence.”