Galileo's Daughter (22 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

When evening falls on the long second day of the

Dialogue,

and the three friends exchange their good-byes, Simplicio leaves promising to review the modern Aristotelian arguments against the Earth’s annual motion, in preparation for the next day’s discussion. Salviati, too, stays up late to study an anti-Copernican text about comets and novas that Simplicio has lent him, and Sagredo lies awake, his thoughts flitting from one cosmological order to the other, eager for a resolution. But somewhere in that second day’s night of reflection, Galileo stopped writing, so that the conversation among the

Dialogues

three characters hung suspended for several years while their author continued thinking through the intricate proofs to be presented, and also tended to other pressing affairs.

The long-promised pension for Galileo’s son at last became real in 1627 through a bull issued by Pope Urban VIII. Vincenzio was to receive a canonry up north at Brescia, along with an annual income of sixty

scudi

—except that he refused the offer. Still attending school at Pisa, twenty-one-year-old Vincenzio admitted that he felt a “bitter hatred of the clerical state.” This confession drove a new wedge between him and his father, and also compelled Galileo to find another recipient for the pension itself. A candidate soon emerged from the ranks of his extended family.

In May of 1627, Galileo received a letter from his brother, Michelangelo, who now carried on their father’s unremunerative musical profession in Munich. Michelangelo proposed to send his wife, Anna Chiara, along with a few of their eight children, to stay with Galileo in Florence for an unspecified length of time, where the family would be safe from the German turmoil of what eventually came to be called the Thirty Years’ War. This conflict had begun in 1618, when enraged Protestant noblemen threw two Catholic governors out the windows of the royal castle in Prague. The “Defenestration of Prague” renewed long-dormant religious bloodshed between Protestant and Roman Catholic states in Germany. In no time the conflict drew in neighboring countries warring for the political prize at stake: control of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. By 1627, the fighting, almost entirely confined to German soil, embroiled Dutch, Spanish, English, Polish, and Danish armies. If impoverished Michelangelo needed a good excuse to export his family to Italy, the war certainly added substance to his personal reasons.

Papal seal of Urban VIII

“This arrangement would be good for both of us,” Michelangelo wheedled. “Your house will be well and faithfully governed, and I should be partly lightened of an expense which I do not know how to meet; for Chiara would take some of the children with her, who would be an amusement for you and a comfort to her. I do not suppose that you would feel the expense of one or two mouths more. At any rate, they will not cost you more than those you have about you now, who are not so near akin, and probably not so much in need of help as I am.”

Anna Chiara arrived in July, with all her children in tow, not to mention their German nurse, for a total of ten additional mouths to feed. Thus Galileo, at age sixty-three, suddenly found himself the head of a noisy household that included his infant niece, Maria Fulvia, two-year-old Anna Maria, Elisabetta, three unruly boys— Alberto, Cosimo, and little Michelangelo—and Mechilde, the dutiful older daughter. Galileo arranged for his eldest visiting nephew, the twenty-year-old Vincenzio, to study music in Rome. He further accommodated the youth by granting to him the papal pension he had secured for his own Vincenzio.

Although Michelangelo’s Vincenzio evinced genuine musical talent, he disdained to work at his lessons. The Benedictine monk Benedetto Castelli, who had taken Galileo’s son in hand in Pisa, had recently been transferred to Rome, where he now tried vainly to keep Galileo’s nephew in line. But this Vincenzio stayed out all night with rapscallions, ran up debts, and flouted religious decorum so flagrantly that his Roman landlord threatened to have him denounced to the Holy Office of the Inquisition.

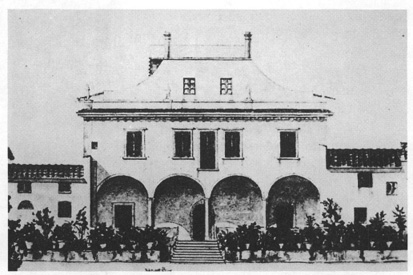

Galileo’s house at Bellosguardo, where he lived from 1617 to 1631

In Brescia, meanwhile, resident clerics ignored Galileo’s transfer of the pension from one Vincenzio Galilei to another: They elected a citizen of their own town to serve as canon. (Galileo waited a few years for the popular Brescian to die and create a new vacancy before he tried to install another family member in that post.)

With his house filled to the rafters, Galileo abandoned Bellosguardo when he next fell ill in mid-March of 1628, taking refuge at the home of acquaintances in Florence.

“Something in the peaceful air today,” Suor Maria Celeste wrote him when he had recovered and returned to his own quarters,

gave me half a hope of seeing you again, Sire. Since you did not come, we were most pleased with the arrival of adorable little Albertino, along with our Aunt, giving us news that you are well and that you will soon be here to see us; yet my delight was all but destroyed when I learned that you have already returned to your usual labors in the garden, leaving me considerably disturbed; since the air is still quite raw, and you, Sire, still weak from your recent illness, I fear this activity will do you harm. Please do not forget so quickly the grave condition you were in, and have a little more love for yourself than for the garden; although I suppose it is not for love of the garden per se, but rather the joy you draw from it, that you put yourself at such risk. But in this season of Lent, when one is expected to make certain sacrifices, make this one, Sire: deprive yourself for a time of the pleasure of the garden.

Galileo had considered undertaking a second pilgrimage to Loreto in 1628, marking the decade since his last call at the Casa Santa. He mentioned the possibility in a letter to his brother, and even suggested taking his sister-in-law, Anna Chiara, along with him on the long trek, but his illness prevented him from making such a trip. Instead, Anna Chiara and her children, whom Suor Maria Celeste now referred to as “the little rabblerousers,” took their leave. Catholic forces in Germany seemed virtually assured of victory at this point, and in any case, after nearly a year, it was time to go home.

Soon after his long-visiting relatives returned to Germany in the spring of 1628, Galileo fell into a tenure wrangle with the University of Pisa. His original appointment to the Tuscan court in 1610 had included a lifetime chair on the university faculty, conferred by Cosimo II. Galileo occupied the honorary position in absentia, with no obligation even to visit Pisa, and no mandatory teaching duties to derail him from his more important mission of discovering novelties and announcing them to the world at large for the greater glory of the grand duke. But the university administration, tired of honoring the old contract, suddenly moved to dissolve it. Galileo fought back with vigor, and with the full support of Ferdinando II, for although his professorial appointment had come through the court, the university paid Galileo’s salary of one thousand

scudi

annually.

By April, Galileo told Suor Maria Celeste of his plans to go to Pisa. In addition to the legal proceedings with the university (which wore on, with and without his presence, for nearly two years before Galileo emerged victorious), he meant to attend Vincenzio’s graduation. Suor Maria Celeste pressed him to do a favor en route for two poor nuns at the convent by purchasing several yards of cheap Pisan wool cloth, for which they had pooled together eight

scudi.

At the Pisan academic ceremonies, Vincenzio collected his doctoral degree in law as the culmination of six years of study. (Galileo himself had never experienced this rite of passage, having left school without completing his required courses.) A more mature Vincenzio now returned home to his father’s house at Bellosguardo, where he turned twenty-two in August. He took to paying regular visits to his sisters at San Matteo. And the following December he delighted Galileo with his decision to marry young Sestilia Bocchineri, whose family held prestigious appointments in the Tuscan court.

MOST BELOVED LORD FATHER

MOST BELOVED LORD FATHER

THE UNEXPECTED NEWS delivered here by our Vincenzio regarding the finalization of his wedding plans, and marrying into that esteemed family, has brought me such happiness that I would not know how better to express it, save to say that, as great as is the love I bear you, Sire, equally great is the delight I derive from your every joy, which I imagine in this instance to be immense; and therefore I come now to rejoice with you, and pray our Lord to protect you for a very long time, so that you can savor those satisfactions that seem guaranteed to you by the good qualities of your son and my brother, for whom my affection grows stronger every day, as he appears to me to be a calm and wise young man.

I would much rather have celebrated with you in person, Sire, but if you would be so kind, I implore you to at least tell me by letter how you plan to arrange your visit with Vincenzio’s betrothed: meaning whether it may be well to meet in Prato when Vincenzio goes there, or better to wait until she is in Florence, since this is the usual formality among us sisters, and surely, given her experience of having been in a convent, she will know these customs. I await your resolution. And in the meanwhile I bid you adieu from my heart.

Your most affectionate daughter,

S. M. Coloste

On the

right path,

by the

grace of God

The family of Sestilia Bocchineri, Vincenzio’s intended, lived above reproach about twelve miles from Florence in the textile city of Prato, famed for its mulberry trees and silkworms. There her father served as majordomo at the Medici’s local palace, while her brother Geri held a Florentine court position at the Pitti. The Tuscan secretary of state had contrived to couple Vincenzio with Sestilia, entirely to Galileo’s satisfaction. The bride brought a dowry of seven hundred

scudi

to the marriage—an amount that would have secured her future in her convent had she not been betrothed instead on the eve of her sixteenth birthday. The wedding date, set for January 29, 1629, allowed the relatives about a month’s time for preparations.