rose early each morning and went flying for several hours before breakfast, just to log more flight time.

|

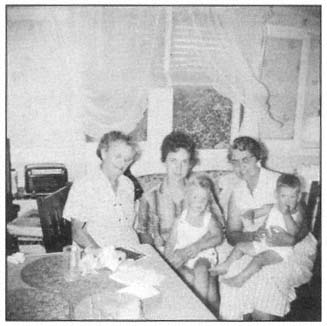

They now had three children, Alan, five, Glen, four, and Gayle, one, and were living in their first home, a four bedroom brick "palace" purchased for under $15,000.

|

Each night Bill and a number of the other student officers would gather in his study. Valerie would bring them food and coffee, and for hours they would review physics and engineering problems.

|

Bill's schedule was so tight that the only break he took was fifteen minutes each evening to eat dinner and watch the news. Sometimes one-year-old Gayle would crawl to Bill's study door, lie on her belly and put her hands through the gap at the base of the door. Bill would see her fingers, come out to hold her for a while, then go back inside.

|

For Valerie, the price of marrying a man who wanted to be an astronaut was as hard and unrelenting as her husband's schedule. She, like Marilyn and Susan, tolerated miserable living conditions in the 1950's in order to further her husband's career. At Bill's first assignment in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, the couple lived for a time in a tiny one-room storefront office, with no air conditioning and the only bedroom window made of glass bricks that couldn't open. This was just as well, as the bedroom faced the town's main street and "there was a cricket epidemic," Valerie remembered. "The whole town was filled with black crickets everywhere." Valerie, used to the comfortable San Diego climate, soon developed a kidney infection which was followed by infectious mononucleosis.

|

Nor were the sacrifices she and the other wives faced merely discomfort and meager living conditions. They also sacrificed careers and university degrees. All three women attended college something few were able to do in the 1950's. Wherever Valerie lived she enrolled at the nearest university, taking courses from astronomy to oceanography, simply because the subjects interested her. Later, when NASA did a background check on her husband to see if he was qualified to become an astronaut, it also investigated Valerie, making sure that she, like Marilyn and Susan, could handle the pressures and challenges she was certain to face. Just as he had to measure up, so did she.

|

|