"That was Frank," Borman said.

|

"Oh, well, likewise with Susan," Collins recovered. "I have not talked to her since last night."

|

For Susan Borman, the battle was not so much over fighting the worry and fear, but preventing anyone from finding out how afraid she was. Her solution was to dull her mind. She would mix herself a drink and try and play hostess as neighbors and friends arrived with their encouragement and food.

|

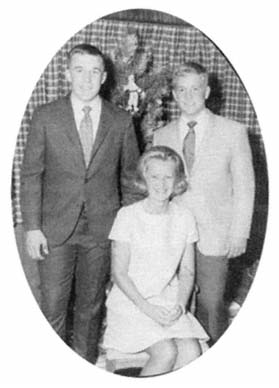

Helping her were her two teenage sons. With the fearlessness of youth and the same boundless confidence of their father, both boys were heedless of the dangers. Separated from his daily grind and high-pressure concerns, they didn't understand the risk and were instead sure that everything would work out. This was simply his day job, and he enjoyed doing it.

|

Their mother, however, was always close by, and they could see how obsessed and worried she was about the flight, almost to the exclusion of food and sleep. In fact, she had eaten so little since launch that at one point Fred sat down with her and demanded that Susan eat something. She shook her head. Food was the last thing on her mind.

|

Undeterred, he put potato salad on a fork and thrust it at her. "Eat!" he insisted. When she still refused, he began to imitate how she would treat him when he would refuse food as a baby. "Open the hanger door, here comes the plane," he sang, aiming the fork at her mouth like a airplane. "RrrrRRRrrRRRRR,"he rumbled, simulating the sound of a propeller plane.

|

Susan laughed, and took a mouthful.

1

|

Just as she had on Saturday night, Marilyn Lovell had difficulty sleeping Sunday. She had dozed, much like the astronauts, sleeping in short restless bursts. Periodically she would get up, go into the kitchen to listen to their voices on the squawk box while smoking another cigarette.

|

Dawn finally arrived, and as scheduled she went to her Monday morning beauty parlor appointment. Then she did some shopping at the local grocery store. At some point that morning she went to visit the Borman and Anders homes.

|

|