"Well, that is what we wanted to do," Borman answered. "It seems that would be the most interesting thing we can show you, but we, you know, had trouble with the lens."

|

Mattingly then began describing to Borman the solution proposed by the video technicians on the ground. First the astronauts needed to take one of the filters from the film cameras and duct tape it to the front of the video lens. Then, with the camera mounted in its bracket, the men could aim the camera by reorienting the spacecraft. "Do not touch the body of the lens while televising," Mattingly told Borman. "Apparently if you put your hands on the [telephoto] lens itself, it causes electrical interference." They were also warned to give the lens's automatic light meter from ten to twenty seconds to warm up. The technicians suspected that the previous day the lens hadn't had time to adjust to the high contrast of light coming from a bright earth surrounded by a black sky. For more than an hour Mattingly and Borman went over these steps, with Mattingly noting that "the show as scheduled is just out the window at the earth only."

|

Borman agreed, though he had his doubts about the lens. "I bet the TV doesn't work."

|

Mattingly hedged, "Well, we won't take that bet, but anyway, we are standing by for a nice lurid description [of the earth]."

|

At 2 PM, they turned on the camera. With Borman as pilot and Anders as cameraman, Lovell became the narrator. Because the camera had no eyepiece, the astronauts could only aim it using instructions from earth or, as Anders noted, by "looking down the side or putting some chewing gum on top." Borman and Anders struggled to keep the earth centered in the camera frame, with Borman maneuvering the capsule to make the major adjustments and Anders fine-tuning the picture by tweaking the camera's mounting.

|

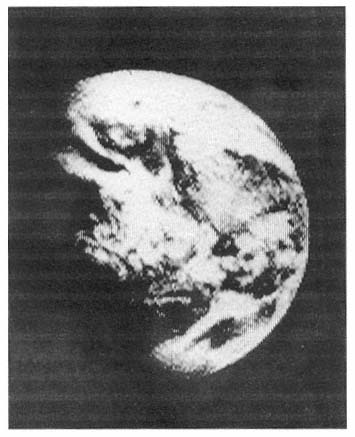

This time the camera lens worked. The astronauts successfully transmitted to earth the first live televised pictures of the home planet as a globe.

|

In many ways, this telecast foreshadowed today's news coverage, where every major event is televised live, and every citizen can watch it happen merely by pressing a button. Yet, because this type of newscast was unprecedented, there were no announcers, no talking heads "analyzing" what everyone was watching. The moment had a freshness and impact gone from much of modern news broadcasting.

|

|