Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (19 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

But it was another member of the coterie, a “cosmopolitan Englishman” named Hugh Woolner, who would kindle stronger feelings in Mrs. Candee. Woolner was eight years her junior and at six-foot-three towered above her small, stylishly dressed form. He was the son of an eminent Victorian sculptor and had been sent to the best schools and to Cambridge, where he had been on the varsity rowing team. Woolner’s upper-class manners were impeccable but his business dealings were less so. After his father’s death in 1892, he had used his inheritance to found a brokerage firm that ran into trouble during the South African war. In attempting to refloat his sinking fortunes, Woolner engaged in a number of illegal practices that resulted in his being barred from the London Stock Exchange. By 1907 he was bankrupt and also a widower, his American wife having died the year before, leaving him with a nine-year-old daughter. Woolner decided to put his daughter in the care of his American in-laws and seek opportunities in the western U.S. states, and by 1910 he had raised enough capital to discharge his British bankruptcy debt, permitting him to once again call himself a company director.

Unaware of Woolner’s checkered business reputation and flattered by his attentions, Helen Candee allowed the suave Englishman to accompany her on long walks around the

Titanic

’s decks, as she describes in “Sealed Orders”: “ ‘

Let us wander over the ship and see it all,’ said she of the cabin de luxe to him of the bachelor’s cabin. So they mounted the hurricane deck and gazed across to the other world of the second class and wondered at its luxury, and further across to the waves and wondered at their clemency.” In an unpublished memoir, Helen also pictures “the Two,” as she calls herself and Woolner, standing together at the prow of the ship. “

As her bow cut into the waves, throwing tons of water to right and left in playful intent,” she wrote, “her indifference to mankind was significant. How grand she was, how superb, how titanic.” This depiction prefigures the famous pose of the lovers in James Cameron’s cinematic epic, but since the ship’s forecastle deck was off-limits to passengers, it may be also be a fanciful one.

Hugh Woolner was not the first charming rogue to have won Helen’s attentions. In her mid-twenties, she had fallen for Edward W. Candee, a wealthy businessman from Norwalk, Connecticut. Her marriage to him produced a daughter and a son, but Candee proved to be an abusive drunk who eventually abandoned his wife and children. Helen could have turned to her family for help—the Churchill Hungerfords were a comfortably off and socially prominent clan—but she chose instead to generate her own income by becoming a journalist. Articles with her byline soon appeared in the

Ladies’ Home Journal

,

Harper’s Bazaar

, and other women’s magazines, and in 1900 she produced a self-help book,

How Women May Earn a Living

, that became a bestseller. The next year she published her only novel,

An Oklahoma Romance

, which was praised by reviewers for its authentic descriptions of the western territory, though whether the passionate love affair it depicts is also authentic is unknown. Helen had spent several years in Guthrie, Oklahoma, in the mid 1890s to facilitate a divorce from Candee. To both seek a divorce and move to a frontier town was highly unconventional for a woman of her background, but Helen had an independence of mind that was well ahead of her time.

By 1904, Helen and her children were living in Washington, D.C., and within a few years the

Washington Times

would describe her as “

a member of the city’s most exclusive smart set” who had “attained a reputation as a brilliant hostess” and at whose Rhode Island Avenue mansion “some of the world’s most prominent persons have visited.” This style of living was made possible by an inheritance she had come into after her mother’s death, but Helen continued to earn money through her writing and by advising some of Washington’s leading ladies on how to decorate their homes. Among her clients was Mathilde Townsend Gerry, Archie Butt’s lost love, as well as both of the first ladies Archie served, Edith Roosevelt and Nellie Taft. Helen had grown up with antiques—a chair owned by

Mayflower

elder William Brewster was a family heirloom—and her advocacy for their use was featured in her 1906 book

Decorative Styles and Periods

. Horses had also been part of her childhood in the Connecticut countryside, and in Washington she rode with Clarence Moore and his wife at the Chevy Chase Hunt Club. Helen was an active campaigner for women’s voting rights and would lead a contingent of smartly dressed equestriennes in the historic Woman Suffrage Parade in Washington on March 3, 1913.

Although fully committed to the cause of female suffrage, Helen declared that, unlike some of the more severe supporters of votes for women, she had no interest in “

dressing like the matron in an asylum.” The social columns often commented on the elegant attire of the “lovely Mrs. Churchill Candee,” who was fond of black velvet and ermine and the large feathered hats then so much in fashion. An equally chic but more modest hat crowned her head as she sat reading on the

Titanic

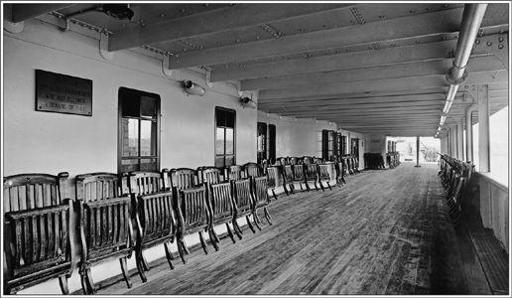

’s enclosed promenade deck, where she usually reserved two steamer chairs, “

one for myself and the other for callers, or for self protection.” Returning there after luncheon one day, Mrs. Candee found all six of her “coterie” waiting by her chairs. In addition to Gracie’s trio and Hugh Woolner, her other admirers were two acquaintances that Woolner had made on board. One was Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, the twenty-eight-year-old son of a Swedish pulp baron who was pursuing technical studies in Washington, and the other was a jolly, rotund Irish engineer named Edward Colley, who had a home in Victoria, British Columbia.

“

We are here to amuse you,” one of them announced. “All of us here have the same thought, which is that you must never be alone.” Her solicitous admirers were well aware that Mrs. Candee was returning to America to be at the bedside of her injured son, Harold. Archie Butt and Frank Millet, two Washington acquaintances, may also have stopped at her steamer chair to offer some polite words of concern during their daily walks around the decks. Ella White’s companion, Marie Young, frequently spotted them out walking together and later described how the “

two famous men passed many times every day in a vigorous constitutional, one [Archie] talking always—as rapidly as he walked—the other a good and smiling listener.”

Helen Candee was frequently to be found reading in a steamer chair on the enclosed A-deck promenade.

(photo credit 1.72)

Marie Young had been a music teacher to the Roosevelt children in Washington and knew who both Archie and Frank were, though she was not an acquaintance. On her regular visits to the galleys on D deck, where she went to check on “

the fancy French poultry we were bringing home,” Marie also enjoyed seeing some of the workings of the ship. She would later describe “the cooks before their great cauldrons of porcelain and the bakers turning out the huge loaves of bread, a hamper of which was later brought up on deck, to supply the life boats.” She had asked the ship’s carpenter to have crates built for the hens and roosters, and when she paid him with gold coins, he thanked her by saying, “It is such good luck to receive gold on a first voyage.” Meanwhile, the hens laid eggs busily, and Marie relayed each day’s count to Ella White, who remained cabin-bound in their C-deck stateroom, recovering from her fall while boarding.

Another passenger who was keeping to his cabin was Hugo Ross, the ailing member of the Canadian “Three Musketeers” who had been brought aboard in Southampton on a stretcher. His companions Thomson Beattie and Thomas McCaffry would often look in on his A-deck stateroom, as would another old friend, Major Arthur Peuchen, a Toronto millionaire, militia officer, and yachtsman. Ross had crewed for Peuchen on his sixty-five-foot yacht, the

Vreda

, while a student at the University of Toronto, and had often joined him in post-race celebrations on the veranda of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club overlooking Lake Ontario. Peuchen had no doubt invited Ross to visit “Woodlands,” his estate on Lake Simcoe north of the city, where boating was combined with rounds of tennis, golf, and croquet on the grassy acreage that surrounded the high-gabled red-brick house. All of this, along with a substantial home at 599 Jarvis, then Toronto’s grandest street, was made possible by Peuchen’s development of an innovative method for extracting acetone (a chemical once primarily used in making explosives) from wood. His Standard Chemical Company owned large tracts of timber in Alberta and factories in Ontario and Quebec, which shipped crude alcohols to refineries in England, Germany, and France. Peuchen’s wide-ranging business interests made him a frequent transatlantic traveler;

the

Titanic

’s first crossing would be his fortieth, and he was aiming to be home for his fifty-third birthday on April 18.

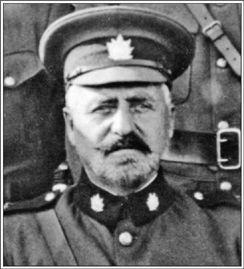

Peuchen was one of thirty Canadians traveling in first class, and they comprise a fascinating sampling of the young dominion’s business elite. If America’s Gilded Age plutocracy was a small world, then Canada’s was a village. Major Peuchen knew most of the prominent Canadians on board, and he was to his shipboard circle what Colonel Gracie was to “our coterie.” The similarities between the two men continue even further: both were born in 1859; both were comfortably off and owed their military titles to fashionable militia regiments; both were similarly mustached (though Peuchen also sported a small goatee)—and both were expansive, often garrulous, men.

Major Arthur Peuchen

(photo credit 1.17)

Though he had booked only a modest cabin on C deck, Arthur Peuchen was enjoying the

Titanic

’s comforts and would later declare, “The

Titanic

was a good boat, luxuriously fitted up—I was pleased with her. But when I heard that our captain was Captain Smith, I said, ‘Surely we are not going to have that man.’ ” Peuchen thought Smith was rather too much the society captain. Opining about captains and ships was a common conversational gambit among the well traveled, and Peuchen no doubt pontificated about Captain Smith to his table companions, Harry Markland Molson, a member of the famous brewing family and director of the Molson’s Bank in Montreal, and Hudson J. C. Allison, who at thirty had already made a killing in Montreal real estate and stocks. Allison was traveling with his young wife, Bess, their two infant children, and four servants they had recently hired in England. Molson, the wealthiest Canadian on board, was a director of one of Peuchen’s companies and had been persuaded by him in London to travel on the

Titanic

rather than wait for the

Lusitania

.

A quiet, unassuming man with a clipped beard and mustache, Molson was still a bachelor at fifty-five—though not of the confirmed variety: his nickname “Merry Larkwand” (a play on “Harry Markland”) had been earned by his reputation as a playboy. In

The Molson Saga

, family chronicler Shirley E. Woods writes that Harry had for some years maintained an intimate relationship with Florence Morris, the attractive wife of one of his cousins. Florence’s husband seemingly acquiesced to the affair—his wife would often cruise alone with Molson on his yacht or stay with him at his summer house—and the ménage à trois was no secret in Montreal society. Before departing for England, Molson had changed his will, leaving one of his houses and a substantial sum of cash to Florence, “

to be unseizable and entirely her own property.”