Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck (10 page)

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

Say a stranger’s car breaks down on your block. Go out and offer them a glass of lemonade or a bottle of water and ask whether they need to borrow anything—a flashlight, your phone, a wrench. I’ve actually never had anybody take me up on these offers; these days, everybody has cell phones and auto club memberships, but they always look and sound really grateful—even moved—that a total stranger cared about what they were going through.

It’s also nice to do as they do in Paris, where passing strangers are likely to greet each other. You’ll walk through a courtyard of a building and cross paths with a woman you for sure will never see again, and she’ll say, “Bonjour, madame,” and you say it back to her. It’s really nice. It’s this little moment in which you’re connected to somebody. They’ve saluted your existence.

After experiencing this in France, I started greeting people everywhere—saying hi to coffee shop and takeout cashiers instead of just giving my order, and smiling and saying good morning to passersby. In time, I came to realize that a stranger is just someone you have yet to treat like a neighbor and that a friendly hello is shorthand for the French phrase,

Ne seriez-vous pas mon voisin?

Or, as Mr. Rogers used to put it, “Won’t you be my neighbor?”

THE TELEPHONE

Sometimes I have this fantasy

in which I march into a quiet restaurant, the drugstore, or a coffeehouse, stand on a chair and launch into a long, loud monologue on Me, Myself, and My Day:

Yoo-hoo! Yooooo-hooo!

Helloo, people of Earth! My name is Amy Alkon, and I really need a tampon …

Fortunately, each of these businesses has numerous visual cues that remind me to restrain myself. The interior of Starbucks, for example, pretty much screams “Starbucks!” and not “church basement AA meeting” or “open mic night at the community theater.” Bizarrely, many other patrons of Starbucks and these other venues think it’s okay to belt out the sordidly boring minutiae of their lives to the rest of us simply because they are holding a small electronic device to their ear.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM HELL: PHONE MANNERS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

When Alexander Graham Bell first got on the phone and said “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you!” Mr. Watson, of course, came running. These days, Mr. Watson might grudgingly answer the phone when it rings—or just let the call go to voicemail and never pick up the message.

Modern telephone technology has transformed our lives in incredible ways and in some pretty sucky ones. The average American thirteen-year-old now has a small gadget in his pocket with more computing power than NASA used to put the first man on the moon.

9

But with such power comes responsibility, or

should

come responsibility, any sense of which is absent from all those bank-line cell phone shouters making the rest of us long to take out our eardrums with one of those pens-on-a-chain.

Many are quick to blame cell phones for the decline of civilization, just as grumblers in ages past probably pointed the finger at those big stone tablets lugged around town by a nobleman’s eunuch. But the real problem isn’t the particular message delivery system; it’s the narcissistic asswad using it.

Even if you are among the considerate, you may want to rethink how you use the telephone. There have been a few changes in what’s considered polite telephone behavior—most strikingly that, in many cases, one of the rudest things you can now do with your phone is to use it to call somebody.

Especially for people under forty, the spontaneous phone call has largely become rude.

Unless you are employed by a police state as a roving interrogator, you probably wouldn’t storm into somebody’s office, sweep their work off their desk, and bark, “Tell me what I want to know right this second!” But, that’s pretty much what you’re doing if you engage in promiscuous phoning—ringing somebody simply because the urge to know

right now

happens to strike you and

right now

happens to be convenient for you.

In general, if you are not on fire, having a heart attack, or in some sort of business where your phone calls are expected and appreciated, the default position on phoning people should be what I have deemed the “Do Not Ever Call” rule.

There are now more demands on our time than ever, along with more ways than ever to reach people that do not require their immediate attention. In addition to the classics—the U.S. mail, a message in a bottle, and telepathy

10

—it is now possible to text, tweet, e-mail, or Facebook-message one’s quarry. If you

must

have a phone conversation with somebody, err on the side of using one of the above options to arrange a mutually convenient time for it.

If that sounds overly picky to you, think about how it feels to get into what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi deemed “flow”—that super-engaged state where you lose yourself in some activity—and then …

BRINNNNG!

Sure, a person could put his ringer on silent to avoid all calls—and then interrupt his work time by fretting that he might be missing an urgent call.

To keep people from phoning you, tell those you meet who want your phone number that you’re “not really a phone person,” and if you give out business cards, see that they include only an e-mail address, no phone number. Naturally, there will surely be some in your life not subject to the “Do Not Ever Call” rule: very good friends, your spouse, your lover, your parents, or other close relatives. Presumably, they will be familiar with the okay times to phone you, although some may occasionally use the telephone as a weapon: “I woke you? How crazy that you’d be sleeping at 6:22 a.m. on a Sunday!” (If this sounds like your mother, snail-mail her a card with your weekend waking hours. Scrawl a smiley on the bottom to take the edge off.)

Before you willy-nilly call those you’re close with, make extra sure you know

their

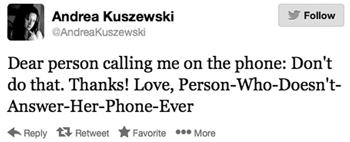

phone preferences. For an increasing number of people, the optimal time to reach them by telephone is never. My nerdywriterfriend Andrea Kuszewski tweeted:

Leave a hang-up at the beep.

Voicemail should not be treated as a content delivery system. A voicemail kidnaps the recipient’s time for as long as it takes to hear that rambling message you left, assuming they don’t rebel and delete it halfway through. (My friend Jackie Danicki refuses to listen to any voicemail longer than a minute and often deletes them in the first ten seconds if they lack promise.) If you must speak your piece—like when your doctor’s office needs your insurance card number and your call goes to her receptionist’s voicemail—do your best to keep it snappy. But, otherwise, unless somebody’s told you that they like or prefer voicemail, consider hanging up and texting or emailing them instead of rambling on: “Hi, it’s Amy. I was just sitting here having Jell-O, petting my dog, and watching Ultimate Fight Club and thought of you…” In general, modern voicemail manners boil down to this: Don’t leave voicemail.

Polite enjoyment of one’s phone features

• Call blocking

Having your call appear on caller ID as “private caller” or “blocked number” can be helpful in getting pus-bags who owe you money to accidentally pick up. But now that we’re all used to getting a caller preview from caller ID, mystery callers creep out a lot of people. If you have call blocking, take that extra three-quarters of a second to dial *82 to disable it before calling friends and family, lest they wonder whether they’ll be picking up to heavy breathing from the pay phone in cellblock D.

• Call waiting

Call waiting is the rudest feature in telephoning, the phone version of The Hollywood Conversation, where some Hollyweasel is talking to you but staring over your shoulder to monitor whether somebody more important has come into the room.

When somebody with call waiting leaves you on protracted hold, don’t let them make you their phone bitch; hang up. If they complain, don’t engage; just restate the obvious: “You were gone for a while, so I hung up.” Next time, they will likely do better.

If you use this feature, be mindful that it’s called “call waiting” and not “call waiting and waiting.” Also, before clicking through to another call, show consideration for the person you’ve been speaking with by using interrupter-dissing language like “Hold on. Gotta

get rid of

this person beeping in.” If you must dump the caller who was there first, make it sound like an emergency. (Remember: Honesty is always the best policy, except when lying your ass off will preserve somebody’s feelings.)

• Your outgoing message

Record your own brief phone message

11

for callers to your cell phone instead of using the phone company’s prerecorded one if that means enabling their rude bill-padding. Certain greedy companies jack up people’s phone minutes usage with their filibuster of a default message, explaining in minute detail what one must do to leave a voicemail. There are still people on earth who don’t know how to do that, but most are members of Amazon tribes whose “phone packages” include an unlimited number of smoke signals.

12

• Your cell phone’s ringer

Telephones carried into public places should be put on vibrate or, better still, on silent—silent like the repeating “g” in “enough is e-fucking-nough” (which is what we’ve all had of “happy hardcore” ring tones and every other ring tone there is).

A public cell phone call is an invasion of mental privacy.

Imagine somebody drilling a big hole in your skull and then grabbing their fast-food trash from lunch and jamming it all in. Welcome to somebody else’s public cell phone call. It’s mental littering. Brain-invasion robbery. You can become a victim simply by going out for pancakes, which, these days, often come with both maple syrup and a big unordered scoop of some cellboor’s

BLAHBLAHBLAH

.

Yes, I’m aware of the saying, “There is no right not to be offended.” And I get that lots of people offend in lots of ways, like by pairing a ginormous, jiggling, hairy belly with a midriff shirt and marching back and forth past where you’re eating. But you can look the other way. You can’t hear the other way.

Cellboors in restaurants and coffeehouses will often justify shoving their conversations on us by sneering, “What’s the difference whether two people are sitting at a table talking or one person’s talking to somebody on the other end of the country?” There

is

a difference. Research by University of York psychologist Andrew Monk and colleagues showed that a one-sided conversation commandeers the brain in a way a two-sided conversation does not, apparently because your brain tries to fill in the side of the conversation you can’t hear. (It doesn’t help that people tend to bark into their cell phones in the way white men in cowboy movies talked to Indians.)

A team at Cornell led by then grad student Lauren Emberson deemed these one-sided conversations “halfalogues” and reinforced Monk’s findings when they tested halfalogues made up of gibberish words against those with words that could be understood. They found that when the words spoken were incomprehensible, the brain drain was removed; there were no costs imposed on bystanders’ attention. So, although many see public cell phone yakking as a noise issue, which it often is, it’s the words being spoken that are the real problem. Basically, even if somebody on a cell phone is trying to keep their voice down, they’re probably giving many around them an irritating case of neural itching.

This mind-jacking is an annoying side effect of the very useful human capacity to predict what others are thinking and feeling and use that information to predict how they’ll behave. This is called “mental state attribution” or “theory of mind” (as in, the theory you come up with about what’s going on in somebody else’s mind). When you see a man looking deep into a woman’s eyes, smiling tenderly and then getting down on one knee, your understanding and experience of what this usually means helps you guess that he’s about to ask “Will you marry me?” and not “Would you mind lending me a pen?”

Unfortunately, this mind-reading ability isn’t something we can turn on and off at will. “It’s … pretty much automatic,” blogged University of Pennsylvania linguist Mark Liberman. “You can’t stop yourself from reading [others’] minds any more than you can stop yourself from noticing the color of their clothes.” But when you’re only getting half the cues, like from one side of a stranger’s cell phone conversation, your brain has to work a lot harder, and it interferes with your ability to focus your thoughts on other things.

“The world is my phone booth!”: Cellboors’ hostile takeover of shared space.

As I noted in chapter 2, a cellboor who takes over a public space like a coffee bar or post office line with his yakking—effectively privatizing shared space as his own—is stealing from everyone there. It’s important to look at it that way because even people who are seriously annoyed at having their attention colonized by some baboon on his cell are often reluctant to speak up. Understanding that we’re being robbed—that the cellboor is hijacking our attention—is the best way to inspire even meeker types to eke out, “

Psst,

Bub—you mind keeping it down?”