Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck (13 page)

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

On blogs and in other discussion forums, if you think you can guard your identity simply by posting under some made-up name or using some techno-trick to hide who you are, think again. You’re sure to get sloppy, as did an employee from the Department of Homeland Security who

almost always

cloaked his IP address (the numerical address of a computer or network a person is posting from) when he was violating numerous Homeland Security policies in pretending to be just an ordinary citizen posting multiple abusive attacks on me on my blog posts criticizing the TSA’s violations of our civil liberties. The attacks by this guy, who used the moniker “Knowing” and posted forty-four times from September 2011 to November 2012, were so rude and relentless that I got curious and looked up the IP addresses that he had posted from. I then discovered that he was a (taxpayer-salaried) Homeland Security employee posting from (taxpayer-funded) Homeland Security servers in Washington, DC, during the workday! No sooner did I reveal this on my blog than his tone changed from vicious and abusive to regretful and apologetic. I demanded his identity and swore I’d go after him and expose him. In his final comment on my site, he wrote, “I know you will pursue me.” Not surprisingly, his colleagues at Homeland Security are not cooperating with my efforts, so rooting him out may take a while longer—and a Freedom of Information Act request. I’m guessing he’s spent at least a few months worrying that he’ll lose his job or be demoted or at least be shamed in the eyes of his superiors—that is, if he isn’t one of the Homeland Security superiors. As we’ve seen in numerous government scandals, including Weiner’s and head spook General David Petraeus’s resignation in the wake of his unencrypted Gmail-conducted affair

19

with his biographer, there’s some pretty high-placed stupidity in the reckless use of technology.

In sharing on social media, keep in mind that even your most carefully thought-out boundaries can wither when you have a strong emotion and the smartphone technology to vent it to the universe in seconds. If there’s a lot at stake for you in emotionally driven overshare, you might make a rule that in the wake of getting enraged or otherwise jazzed up while online, you’ll give yourself a little time-out before you let your fingers do any tap-dancing on any keyboards.

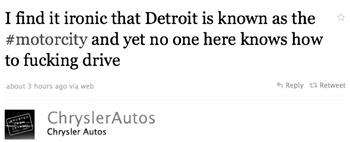

A time-out rule is especially important for anyone who uses social media as part of their job. Scott Bartosiewicz, a Detroit-based social media strategist working on the Chrysler account, decided to blow off a little frustration on Twitter when traffic was making him late to work. This turned into the perfect strategy for getting himself canned when he tweeted a message on the Chrysler feed that he thought he was tweeting on his personal account:

PRIVACY: IT’S REPORTEDLY DEAD, BUT IT SHOULDN’T BE.

Even before our government started logging your calls to your grandma, blogger Greg Swann deemed privacy “an artifact of inefficiency,” explaining that what we’ve thought of throughout our lives as privacy “has simply been a function of inefficient data processing tools.” In other words, it’s not that we never used to reveal so much because we had better character. We just lacked the technology to depants each other in the Global Village’s town square.

Now that we have that technology, many seem to believe that their life and everyone else’s are there for the uploading. If something happens, it simply

must

be posted, tweeted, and Facebooked, and if something isn’t, it must not matter or maybe doesn’t even exist. (If a tree falls in the forest and nobody’s around to video it and upload it to Facebook…)

But, is it really a matter of compelling public interest that three days ago, while waiting in your car for the light to change, you picked your nose? And just because some guy in the next car was quick to catch your nose-digging with his phone and post it to YouTube, should it really be preserved for eternity like a bug in amber?

Technology’s impact on privacy isn’t a new issue. “Numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the housetops,’” wrote Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in the

Harvard Law Review

in the 90s—the 1890s. They were worried about the advent of affordable portable cameras and dismayed at the way newspapers had begun covering people’s private lives.

Brandeis and Warren explained that a person has a right—a natural human right—to determine to what extent their thoughts, opinions, and emotions and the details of their “private life, habits, acts, and relations” will be communicated to others. They noted that this right to privacy comes out of our right to be left alone and that it applies whether an individual’s personal information is “expressed in writing, or in conduct, in conversation, in attitudes, or in facial expression.”

This has not changed because of what’s now technically possible: how it takes just a few clicks to Facebook or Instagram an embarrassing photo of a person or blog their medical history, sexual orientation, sex practices, financial failings, lunch conversation, or daily doings. No matter how fun and easy the technology makes immediately publishing everything about everyone and no matter how common it’s become to violate everyone’s right to privacy, each person’s private life remains their own and not a free commodity to be turned into content by the rest of us.

Where privacy ends and content begins

Sometimes it is fair game to yank somebody’s privacy: to publish their name, image, or whereabouts or other information about them that they’d rather not have made public. Harvard’s Digital Media Law Project advises that the law protects you when you publish information that is

newsworthy

, meaning that there’s “a reasonable relationship between the use of the (person’s) identity and a matter of legitimate public interest.”

Brandeis and Warren pointed out that politicians and other public or quasi-public figures have, to a great extent, “renounced the right to live their lives screened from public observation.” They explained that the details about a would-be congressman’s habits, activities, and foibles may say something about his fitness for office, whereas publishing something about, say, a speech impediment suffered by some “modest and retiring individual” would be an “unwarranted … infringement of his rights.”

Still, private individuals sometimes do things that justify our stripping them of their privacy. Say some lady parks her BMW convertible in a handicapped space (sans disabled plate or placard) and jogs over to the dry cleaner. She’s gambling that no ticket-giver will come by before she’s back. She’s also taking advantage of how, anywhere but in a small town, we’re largely anonymous to the people around us, removing the natural constraint on rude behavior—concern for reputation—that’s in place when people you know can see the hoggy things you’re up to. We restore the reputational cost by webslapping her: taking her picture and blogging, tweeting, and Facebooking it in hopes of shaming her (and compelling other inconsiderados who see the posts) into parking like less of a douche in the future.

A webslapping is also in order for rude people who have

voluntarily given up their privacy

by bellowing their cell phone conversation so loudly that everyone seated around them in a restaurant is forced to listen to it, which makes it a public conversation. You don’t, however, have the right to blog, tweet, Facebook, or otherwise broadcast a

quiet

conversation you’re able to overhear between people seated behind you, assuming they aren’t talking about a plot to blow up the State Department.

And say a man is “guilty” only of attending a dinner gathering. In my advice column, I answered the letter of a man, signing himself “Publicized,” who is widely known and admired for his business accomplishments but values his privacy. Unbeknownst to him, his presence at a dinner party was tweeted by the host’s cousin, a man who “rudely spent most of the evening thumbing” his smartphone. The cousin was maybe trying for status by association (being a guest at the same dinner party as somebody who’s somebody) or, like many people, feels compelled to persistently flick information out on social media as a sort of digital proof of life.

“Publicized” only found out about the tweet upon getting home, when he was surprised to receive an e-mail from a distant acquaintance asking, “How was dinner at Elaine’s?” Days later, he met a former colleague for lunch at a restaurant. He discovered that the colleague had tweeted about the lunch upon coming home to a handful of e-mails from those who’d seen the tweet. And no, these tweets wouldn’t be a big deal—or any deal—to every person, but they were to “Publicized,” and rightfully so.

Privacy plunderers will argue that a restaurant is a public place. This is true, but a man’s appearance at that restaurant is not “newsworthy” unless he’s sticking the place up. And while a man’s desire for privacy is valid if he simply isn’t comfortable being turned into a newsbit, there may be compelling reasons a person would not want his whereabouts published, like if he turned down three other dinner invitations to go to the dinner he ended up attending.

Of course, because so many people now believe others’ privacy is theirs for the violating, if you’d like your private life to remain private, you may need to be proactive about it when you’re invited somewhere. Obviously, if you see somebody’s about to take your picture, you can either bow out of the shot or tell them that you don’t want to appear in social media. Though many people have just resigned themselves to the idea that privacy is over, others are increasingly cognizant that privacy violations can be a real problem for some. The idea of a “what happens at dinner stays at dinner” social media embargo might be worth floating to a host if you aren’t near-strangers and if you think they might be open to the notion that sharing everybody’s everything goes a little far.

There’s a policy like that in place at a monthly writer/pundit dinner I go to—a policy that I think makes those in attendance feel freer to speak their minds, knowing that something they happen to blurt out while sloshed won’t be used against them. The policy was announced in the invitation e-mail at one point and then just understood and passed on to future guests by those of us who are regular attendees. As I wrote to “Publicized,” in the wake of one of these embargoes, guests will just have to satisfy themselves with being rude in old-fashioned ways: hogging the mashed potatoes, passing gas and looking scornfully at the guest next to them, and rummaging through the host’s medicine chest … but refraining from uploading a shot of its contents to Instagram or Flickr.

Having regular sex with someone doesn’t allow you to roll back their privacy to that of a convicted serial killer.

Getting into a relationship doesn’t entitle you to demand your partner’s e-mail and Facebook passwords so you can subject his digital life to regular cavity searches. His inner life—and Internet life—still belong to him, as does the decision of which hopes, dreams, and really tasteless forwards to share with you. Anything he doesn’t specifically invite you to see should be considered off-limits—even if you can guess his password or seize the opportunity to take a little tour of his browser history while he’s in the john.

A common suspicion is, “If you aren’t hiding anything, why would you care whether your girlfriend can read your e-mail, Facebook messages, whatever?” A woman, writing me for advice, asked me that when her boyfriend of two years refused to be bullied into handing over his passwords. I explained that a desire for privacy isn’t evidence of sneakiness.

20

People show different sides of themselves to different people, and her boyfriend would likely feel curtailed in who he is and how he expresses himself if Big Girlfriend is always watching. Giving her access to his e-mail would also be unfair to people who correspond with him, kind of like putting them on speakerphone without their knowledge. If he caved and gave her access to his e-mail, the fair thing for him to do would be the humiliating thing: send out an e-mail to everyone he’s ever met and anyone who might ever write him, disclosing the possibility that any message they send him could be read by The Warden. (Subject line: “I’m whipped.”)

There is, however, an alternative to turning a relationship into the world’s tiniest police state, and that’s putting in the time and effort to figure out whether a person is ethical

before

you get into a committed relationship with them. As I wrote to the woman, “if you can’t trust your boyfriend, why are you with him? If you can, accept that his information is his property, and leave him be when he closes the bathroom door to his mind.”

Your relationship needs a privacy policy.

Each person in a relationship gets to set the standard for what the other partner can blog, tweet, Facebook, Flickr, or otherwise share about them—if anything. That standard should be agreed upon in advance and maintained in the event of a breakup.

Should be

, that is. But, keep in mind that breakups caused by cheating tend to make a partner feel less compelled to honor any prior agreements and, at the same time, make them feel more compelled to vent to anyone and everyone who will listen, including three fishermen who were able to pick up a Wi-Fi signal on their trawler off the coast of China.