Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck (9 page)

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

Miller wasn’t sure what to do. He has daughters and worried that the poo-flinger might be a crazy. He finally called the head of security for his community and showed him the video. The security guy talked to the neighbor and gave him three tickets—one for improper pet waste disposal, one for leash law violations, and one for littering. Best of all, he ordered the guy to come pick up the dog droppings, which he did.

Miller’s video, “Dog Crap Booby Trap,” went viral, and the story was covered on numerous TV stations and in

The New York Times

. But, even if your perp never sees your video or signs, others spotting them are likely to be deterred from behaving jerkoffishly in your neighborhood in the future—not because you’ve transformed them into better human beings but because you’ve reminded them that every nosy neighbor peering over their fence has a smartphone.

For rudesters you only hear in the act, I suggest posted signage—or, as I like to think of it, the “Hey, asshole!” flier.

8

In my neighborhood, for example, some self-important Hollywood bigwhoop started walking his dog at 5 a.m.—while shouting showbiz lingo into his phone at colleagues in a different time zone. He stopped after I typed a note in big letters, printed it on hot-pink paper, and posted it on my fence before going to bed:

Hey, guy on cell phone at 5 a.m. The houses on this block are actually not a Hollywood set but real homes with real people trying to sleep in the bedrooms. Thank you.

The Tragedy of the Asshole in the Commons

There are homeowners who’d start the second Hundred Years’ War to defend the sanctity of their property, but a half-block from their property line, everything changes. In fact, some stranger could come by their block in a truck, release a half-dozen feral cats, and then toss a stack of old mattresses onto the street, dump out several drums of used motor oil, and light the whole mess on fire. In response, these fierce defenders of private property would busy themselves with their petunias.

This “Ain’t

my

land!” response to the trashing of public spaces illustrates what biology professor Garrett Hardin referred to as “the tragedy of the commons” in his 1968 essay on overpopulation. In a space owned by nobody and shared by many, the piggy can take advantage by grabbing more than their fair share of resources or by slopping up the space, ruining it for everyone.

One solution to the tragedy of the commons is private property ownership, but that doesn’t solve the problem of the neighborhood corner used as a dumping ground. What does is

acting

like we have shared ownership of public spaces and getting as indignant about people’s polluting them as we would if they were redirecting traffic across our front lawn.

That sentiment—feeling like part owner of my neighborhood—prompts me to speak up when I see people trashing it. When I manage to photograph them in the act, I sometimes create what I think of as low-tech blog items (phone-pole “blog posts” like the one at the start of this chapter, which I staple to the poles on both street corners by my house). In some of these, I include a few words encouraging my neighbors to feel a sense of ownership for our neighborhood and to say something to those uglying it up.

One day, I was disgusted to come home to bags and boxes of garbage dumped on the grassy strip lining my cute street.

To my surprise, the trash pile included a calling card of sorts: a name and address on a UPS label on a box of window treatments ordered by a woman Google told me is the wife of a top foreign surgeon. Facebook said she and her husband live abroad, but she’d had the window treatments shipped to somebody’s ritzy address in Pacific Palisades—a $2.6 million house overlooking the ocean, in a neighborhood where they surely have trash pickup.

That address label, flaunting itself on the box, suggested that the dumpers may have been stupid enough to leave other identifying information. I put on gloves and rifled through the boxes and bags and found an invoice for the curtain order in the wife’s full name, as well as a boarding pass with the surgeon husband’s name, flight, and seat number. Other items I dug out suggested that they were spending the Christmas holiday in Los Angeles (with a day trip to the Cabazon outlet mall and stops at fast-food outlets along the way). Upon further googling, I surmised that the Palisades address belongs to friends of theirs to whom they’d had the window treatments shipped, probably to avoid paying the postage to their home country.

I messaged both the surgeon and his wife on Facebook and told them to come get their refuse.

Of course, this could have been their opportunity to say they weren’t the dumpers but victims themselves. You never know; there could be a gang of garbage robbers operating in Richville, hauling shopping bags and boxes of trash miles and miles away to my neighborhood in hopes of tarnishing an innocent couple’s reputation.

No response.

Grr.

Double

grr

.

I posted the story and photos on my blog and on social media, naming names (hoping the blog item would be picked up by bloggers in their country).

Still no response.

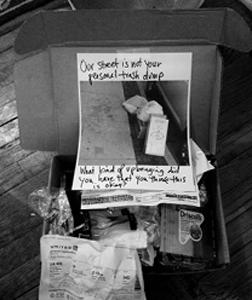

Well, surely, their trash had to miss them. I boxed up a sampling of it with a photo of the dumping and, for a very well-spent $3.69, mailed it to them at the ritzy address where the window treatments had been sent.

Note reads:

“Our street is not your personal trash dump. What kind of upbringing did you have that you think this is okay?”

No, they never did come get their trash, and I never heard either a word of denial or an apology from them. The garbage is long-gone from my street, but the piles remain on the Internet, where, as of September 15, 2013, when you google the wife’s name, the first entry that comes up is my blog item.

Although I didn’t get the resolution I’d asked for, the experience underscored something I learned while I was tracking down my stolen pink 1960 Rambler (which I eventually recovered): Even if you never get your perp to return what they took or otherwise make amends, one of the best ways to stop feeling victimized is to refuse to roll over and take it like a good little victim. And I have to say, it’s hard to keep feeling victimized when you’re walking out of the post office snickering to yourself after mailing a trash sampler and a scoldy letter to some tony Pacific Palisades address and imagining somebody’s fancy friends calling them up to ask them whether they maybe littered in Venice.

Mailing them that package—along with going after them like a gnat with web privileges—also sent them (and any would-be litterbugs who saw my blog item) a couple of important messages: Sometimes, the “easy way out” isn’t so easy on your reputation. Also, because people are strangers doesn’t mean you get to turn their lives into your personal trash dump—both because it’s not nice and because you never know when you’ll dump trash on the street of some nutbag who has not only a problem with that but rubber gloves, a broadband connection, and a penchant for going all Nancy Drew on your ass.

Turning the strangerhood into a neighborhood: How to create community.

I get that most people don’t have it in them to go all medieval schoolmarm on the rude as I do, but anyone can do the little things that bring neighborhood residents together, making them people to one another instead of people who speed past one another in their cars.

• Create a neighborhood lending library.

Dollhouse-like book hutches are popping up in neighborhoods across the country, thanks to the Little Free Library movement (

littlefreelibrary.org

), started in Wisconsin by Todd Bol in memory of his late book-loving schoolteacher mother. Sherman Oaks, California, resident Jonathan Beggs built and stocked one of these book hutches outside his house, where anyone is free to take a book or leave one. “It has evolved into much more than a book exchange,” reported Martha Groves in the

Los Angeles Times

. “It has turned strangers into friends and a sometimes impersonal neighborhood into a community. It has become a mini-town square, where people gather to discuss Sherlock Holmes, sustainability and genealogy.”

Here’s the Little Free Library I patronize in Venice, California, created from a vintage beer case and put out by Susan and David Dworski. (That’s Mojo, the librarian, on the top left.)

• Charity begins at the home next door.

Enlist neighbors to help an elderly resident with faraway relatives or somebody who’s going through something really difficult, like chemo.

• Start a neighborhood association.

Ask neighbors to join a neighborhood e-newsletter mailing list. Some of these just announce the occasional crime alert, but I love the neighborhood bulletin board feel of the

Venice Walk Streets Neighborhood Association

e-newsletter, with items like this one (complete with the hurried spelling):

Neighborhood Carwash

Willie is a nice responisble teenager in our neighborhood who is looking to keep your cars clean. I checked him out; he does a really good job.

Having your neighbors’ e-mail addresses also allows you to stand together as an organized group. This is helpful should you need to take action against somebody who repeatedly goes all 800-pound assholezilla on your neighborhood (like by illegally doing construction at 6 a.m. on Sundays, and never mind the noise laws because the police are too short-staffed to come out and ticket violators).

• Invite, invite, invite.

Throw neighborhood potlucks, block parties, movie nights (showing a classic movie on a garage door covered with a king-size bedsheet). Have an all-block yard sale, a neighborhood cleanup, a twice-a-year wine and cheese gathering at somebody’s house. Start a neighborhood playgroup—for kids, that is. The adult sort with the bowl of keys brings the community closer in ways some may end up regretting.

• Band together and take over for lame-ass government.

When government is failing you, don’t sit on your collective hands. Consider doing as a bunch of people did in Hawaii. When Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources didn’t have the $4 million it estimated it would take to fix an access road to Kauai’s Polihale State Park, local businesses and residents banded together and fixed it themselves. Mallory Simon reported on

CNN.com

that Ivan Slack of Napali Kayak, who needs the park open to keep his company’s doors open, donated resources. Other businesses and residents rounded up machinery and manpower, and together they completed $4 million in roadwork for free in eight days.

Don’t be geographically snobby about whom you treat like a neighbor.

As I noted in the beginning of this book, being around strangers all the time can be really cold and alienating unless we regularly take steps to remedy this with some generosity of spirit. The way I see it, a neighbor is anybody you treat like a neighbor.