Grant and Sherman: The Friendship that Won the Civil War (38 page)

Read Grant and Sherman: The Friendship that Won the Civil War Online

Authors: Charles Bracelen Flood

Tags: #Biography, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction

BOOK: Grant and Sherman: The Friendship that Won the Civil War

10.79Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Confederate general James Longstreet. Grant’s West Point classmate, he was a cousin of Grant’s wife, Julia, and best man at their wedding. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

General Joseph E. Johnston. Robert E. Lee’s West Point classmate and friend, Johnston was the Confederacy’s master of defensive and evasive maneuvers. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

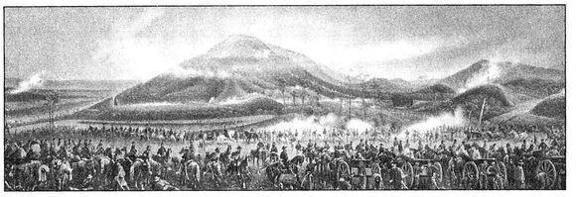

During Grant’s attack on Lookout Mountain at Chattanooga., the weather deteriorated so rapidly that the upper part of the mountain disappeared from view. The ensuing fight became known as “The Battle Above the Clouds.” (U.S. Army Center of Military History, Army Art Collection, Fort McNair, Washington, D.C.)

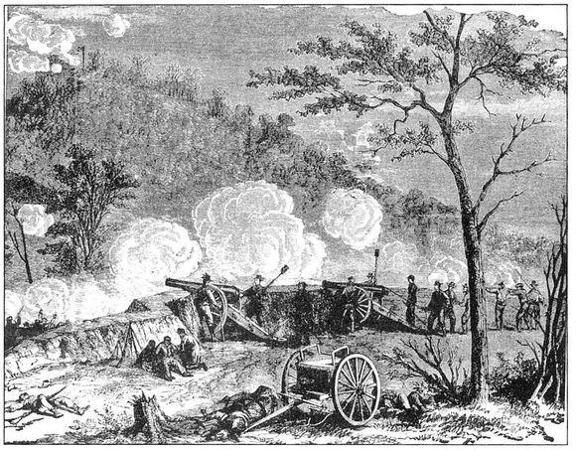

Johnston’s decisive repulse of Sherman’s attacks on Kennesaw Mountain in (Georgia underscored the fact that Sherman was better at executing such sweeping moves as his March to the Sea than at fighting pitched battles like this, (Rights owned by the University of Mississippi Press)

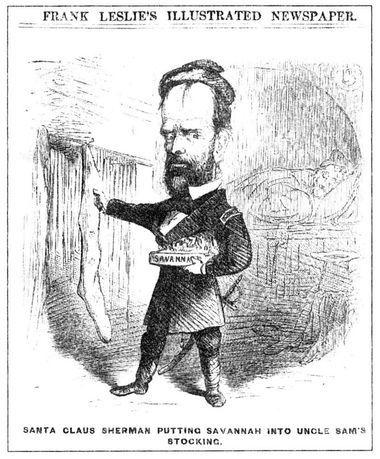

Sherman’s bold and brutal March to the Sea, moving from Atlanta to the coast, resulted in the capture of Savannah on December 21. 1864. Sherman wired Lincoln. “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah.” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

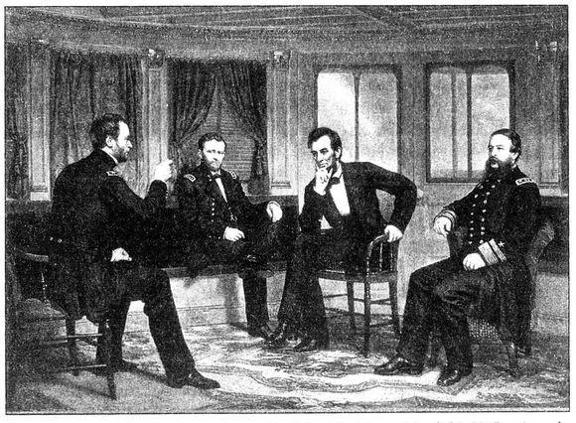

A representation of the historic meeting at City Point, Virginia, on March 28, 1865, as Lincoln met with Grant and Sherman to Discuss the closing phases of the war. LEFT TO RIGHT: Sherman, Grant, Lincoln, Admiral Porter. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

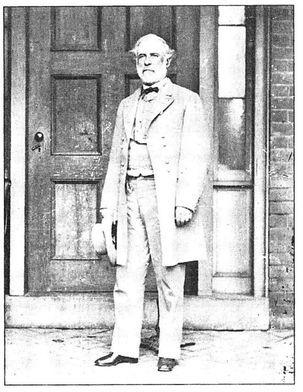

General Robert K. Lee. This photograph was taken by Mathew Brady a few days after Lee’s return to his house in Richmond, Virginia, after surrendering his Army of Northern Virginia to Grant at Appomattox Court House. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

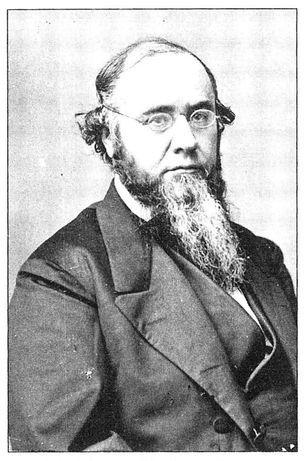

Lincoln’s able, irascible, dictatorial secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

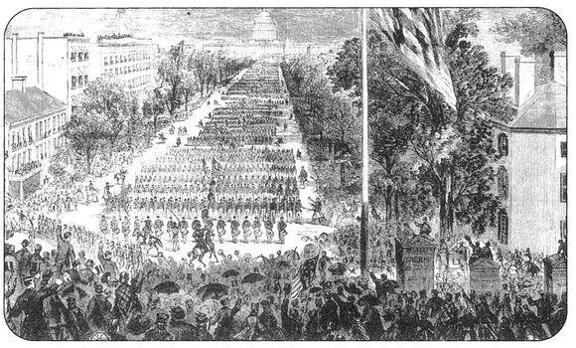

A contemporary drawing of the two-day Grand Review, held in Washington in May of 1865. It was the (Union’s farewell to its victorious army. With Grant and Sherman on the reviewing stand, 135,000 men, most of them soon to he demobilized, marehed past wildly cheering crowds, Rights owned In the of Mississipi Press)

When Grant understood what Sherman wanted to do, he gave his approval for the campaign to march into the heart of the South, headed for Atlanta, which was a vital center for manufacturing and the storage of supplies, as well as being a major railroad hub. Whether Sherman hoped even then to extend this immense movement another 225 miles from Atlanta to Savannah, to complete his epic March to the Sea, is not clear. What is abundantly clear is that, in good part due to his association with Grant, the Sherman of 1864 bore no resemblance to the man who in 1861 had begged Lincoln not to make him the departmental commander in Kentucky but to keep him always as a second in command, serving directly under a superior officer. Even to move his headquarters down to Chattanooga from Nashville meant that Sherman had to leave his most secure, heavily supplied base 110 miles to his rear, connected to his forward headquarters by a single-gauge railroad track that could be struck by Confederate cavalry raids, but he was not looking to his rear. Sherman needed thirteen hundred tons of supplies a day for his hundred thousand men and hoped that the railroad would bring forward as much of that as possible, but he also intended to live off the land, in the heart of the Confederacy, and travel light as he went. (Sherman underscored his intention to carry a minimum of supplies and equipment when he wrote, “My entire headquarters transportation is one wagon for myself, aides, officers, orderlies, and clerks.”)

As spring came to Washington, Grant first had a different kind of battle to fight. In his effort to add to the combat strength of the Union Army, he was sending to the front thousands of soldiers who had been assigned to garrison duty or to guard supply lines. Relying on the traditional civilian control of the military, Stanton told Grant that he was pulling too many men out of the defenses of Washington and ordered it stopped. When Grant politely replied, “I think I rank you in this matter, Mister Secretary,” Stanton answered, “We shall have to see Mister Lincoln about that,” and they walked from the War Department building over to the White House, which was next door.

While Lincoln listened, with Grant remaining silent, Stanton set forth the matter as he saw it. When he finished, Lincoln smiled and said, “You and I, Mr. Stanton, have been trying to boss this job, and we have not succeeded very well with it. We have sent across the mountains for Mr. Grant, as Mrs. Grant calls him, to relieve us, and I think we had better leave him alone to do as he pleases.”

As Grant readied himself to fight Lee, some of the officers of the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia made disparaging remarks about him. Now, they said, Grant would find out what real opposition was. Julia Grant’s cousin James Longstreet, back with Lee’s army in Virginia after seeing how Grant had turned around the situation after Chickamauga by the victory at Chattanooga, warned them not to underestimate his old West Point classmate and friend, whom he had seen in constant fiery action when they fought in the same regiment during the Mexican War. He said to one officer, “We must make up our minds to get into line of battle and stay there, for that man will fight us every day and every hour till the end of this war.”

Other books

The Hooded Hawk Mystery by Franklin W. Dixon

Shane by Vanessa Devereaux

Broken Fall: A D.I. Harland novella by Fergus McNeill

Amber Brown Wants Extra Credit by Paula Danziger

The Road to Reckoning by Robert Lautner

Lonesome Traveler by Jack Kerouac

You Shouldn't Have to Say Goodbye by Patricia Hermes

Staff Nurse in the Tyrol by Elizabeth Houghton